"Because of My Mother's Bracelet, I Discovered Something That Was Hidden From Me All These Years"

After growing up disconnected from her Yemeni heritage, Menucha Cohen received a bracelet from her mother that opened her eyes to untold family stories.

(In the circle: Menucha Cohen, Background Image Credit: Sadan Productions)

(In the circle: Menucha Cohen, Background Image Credit: Sadan Productions)Are you familiar with the stories of the Yemenites who immigrated to Israel and were asked to throw away their jewelry to "not burden the plane" before boarding in Yemen? Menucha Cohen knows these stories from the most painful perspective, as her parents were in those situations and witnessed them closely.

Menucha heard these stories as a child but did not attach much importance to them. "Although I grew up in Rosh HaAyin, in a traditional Yemeni family," she notes, "I married an Ashkenazi man and distanced myself greatly from my parents' Yemeni culture."

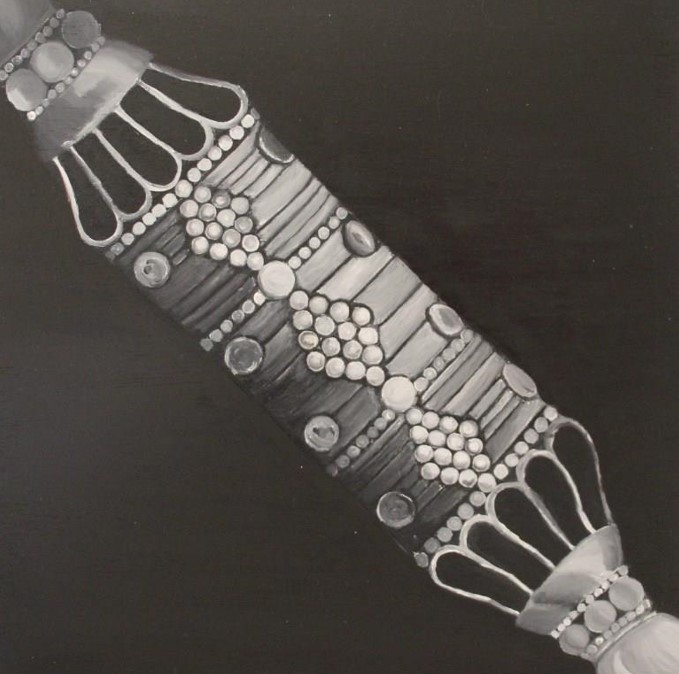

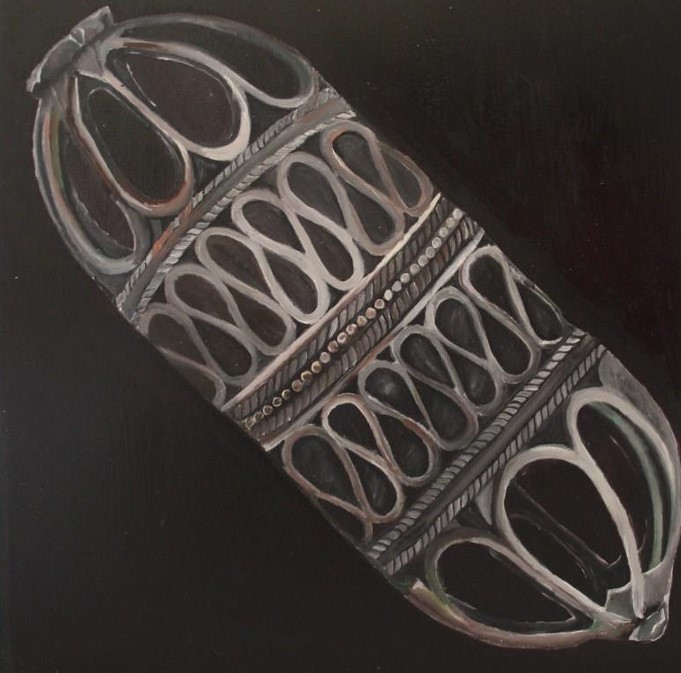

Over the years, Menucha became an artist and curator in Israel and abroad, and she is also very active socially, but she never engaged with Yemen. What eventually brought her back to Yemeni heritage was a unique and rare bracelet she received from her mother, which exposed her to an entire world she was unaware of, and even seemed to have been erased from Yemeni history during the immigration to Israel.

The Secret of the Bracelet

"When my mother got older, she decided to distribute her jewelry among us," Menucha recalls the beginning of the story that shook her life. "I received from her a Yemeni bracelet, made of silver. At that moment, I asked my mother to tell me about it, who made it, and where it came from. This conversation opened a window for me to an entire world of Yemeni culture, which as a child and teenager I never related to. Unfortunately, my mother passed away before she could expose me to all the fascinating stories, but what she did tell me was enough for me to understand that I wanted to continue investigating the subject and hear more and more."

Credit: Sadan Productions

Credit: Sadan ProductionsMenucha read many books on the subject and also spoke with women who lived in Yemen. "It turns out the value of jewelry for Yemeni women was far beyond what one might imagine," she notes, "for the jewelry represented their social and economic status, it was also part of the bride’s dowry and a prerequisite for marriage. In truth, after my wedding, my mother insisted on taking me to the Yemeni jeweler, Shimon Ovadia Salah z"l, to buy me a set of Yemeni jewelry. I didn't understand why I needed them at all, and I kept them only because I received them from my mother. Today, I understand that it was very important for her to preserve the tradition. Now that I am interested in the field, I feel that this is really closing the circle with my mother."

But what was so special about the jewelry in Yemen?

"In Yemen, it was customary for women to wear jewelry from the moment they were born," Menucha explains. "These were jewelry given to them as gifts by men—to a married woman by her husband, and to a girl or young woman by her father. One could recognize each woman's status by her jewelry, as over the years, additional pieces were given on various occasions. There were jewelry pieces awarded for specific events, such as when a girl matured, when she got engaged, and of course, in preparation for the wedding as part of the dowry. When a woman was widowed, the jewelry gradually diminished because she had to maintain herself and was forced to sell some of it."

Credit: Sadan Productions

Credit: Sadan ProductionsAt what age did Yemeni girls receive their first piece of jewelry?

"Usually at age 0, with birth," Menucha explains. "My older sister was born two days before immigrating to Israel, and in pictures, you can see she is wearing a silver piece on her "garush"—her little head covering."

Menucha also mentions that apart from the fixed jewelry for weekdays, Yemeni women had special jewelry for joyful events and jewelry for Shabbat. "The unique aspect of Shabbat jewelry was that it was sewn into the clothing to avoid the issue of 'carrying' on Shabbat according to halacha," she clarifies. "In fact, at every stage of life, a father would give his daughters jewelry to ensure their future and livelihood because when the husband would pass away, the only thing left for a woman was her jewelry to support herself with."

Credit: Sadan Productions

Credit: Sadan Productions Credit: Sadan Productions

Credit: Sadan ProductionsUnforgivable Injustice

Menucha emphasizes that the more she dealt with the subject, the more she began to understand the magnitude of the injustice done to the Yemenite immigrants upon their arrival in Israel. "It began with the Yemeni authorities ensuring that women left their jewelry behind. We were always told that the jewelry was taken from the women before they boarded the plane, but I never understood the magnitude of the fracture. Because with the jewelry, their status, memories of their husbands, and even their financial means to support themselves were taken away. These women arrived in a new country, essentially penniless, with no way to earn a living."

Credit: Sadan Productions

Credit: Sadan Productions Credit: Sadan Productions

Credit: Sadan ProductionsAdditionally, Menucha claims that a great injustice was also done on the Israeli side towards the jewelers from Yemen. In Yemen, they were highly regarded and considered opinion leaders, but when they arrived in Israel, there was no one to give them the respect they deserved. "For example, there was the famous jeweler Shlomo Araki, whom the Yemeni king himself prevented from leaving Yemen, claiming he had to first train Islamic jewelers to continue the craft. Araki was also the one who produced the king's silver and minted the coins in Yemen. He had the highest status, and yet when he arrived in Israel and approached 'Bezalel,' there was no one there to recognize his abilities, and he was made an apprentice. This led him to avoid engaging in jewelry making in Israel and work in agriculture instead. We all lost the unique craftsmanship of his jewelry."

The understanding of the heritage that was taken from the Yemenites is what led Menucha to launch an exhibition set to be displayed at the 'Tribal Art Gallery' on Ba'alei Melacha Street in Tel Aviv. "In the exhibition, I don't showcase the jewelry itself," she emphasizes, "but rather paintings where I have painted them. I deliberately painted only parts of each piece to show the lack of completeness, to illustrate everything that was taken from us."

Credit: Sadan Productions

Credit: Sadan Productions Credit: Sadan Productions

Credit: Sadan Productions Credit: Sadan Productions

Credit: Sadan ProductionsAnd where did the jewelry that you painted come from?

"I mainly based my work on the jewelry that was in my family and then expanded to include additional pieces from various regions, created by jewelers from Yemen and Israel. There will also be Yemeni jewelry from a well-known collector from Rosh HaAyin, and I personally intend to wear some of the jewelry at the opening of the exhibition. I feel they are truly a part of me because, through this engagement, I reconnected with my Yemeni heritage."