Beginners Guide

When “Trust Me, It’s Kosher” Isn’t Enough

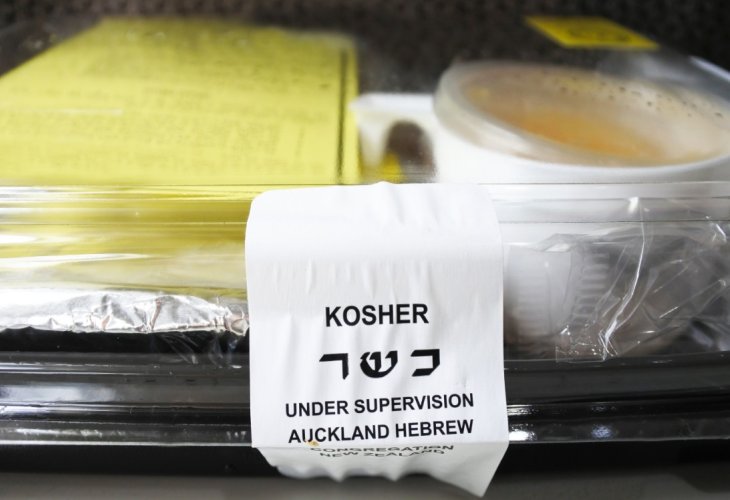

Why personal trust and good intentions are not enough when it comes to kashrut, and what one restaurant owner’s dilemma reveals about the importance of kosher supervision and certification.

- Hidabroot

- |Updated

(Image: shutterstock)

(Image: shutterstock)When a Restaurant Asks Facebook to Decide Its Kashrut

In today’s digital age, many businesses maintain active social media pages. They post updates, promote specials, and interact with customers. But how often do you see a business asking its followers to weigh in on a serious operational decision?

Two weeks ago, I encountered exactly that. A Jerusalem restaurant owner posted on Facebook asking his customers for advice on a major issue.

“Dear friends, we need your help,” he wrote. “We are dealing with a serious matter and would love to hear your honest opinions.”

The Question Behind the Post

The issue turned out to be the restaurant’s kosher certification.

For years, the restaurant had displayed a kosher certificate from the Jerusalem Rabbinate. But now the owner decided to share what he described as the truth. According to him, the supervision was largely symbolic.

“The supervision from the Rabbinate has been mostly fictional,” he wrote. “The supervisor came to collect a check and maybe stopped by once a month, but didn’t really supervise. Everything here is kosher because our staff cares about keeping kosher, not because there’s a certificate on the wall.”

At first glance, one might assume the owner was considering switching to a different kosher authority with more hands-on supervision. But that was not the case.

Cutting Supervision Altogether

What the owner was really debating was whether to do away with kosher supervision entirely.

After moving to a new location, he explained, the Rabbinate informed him that supervision fees would increase. The reasons given, he claimed, were a change in kitchen staff and the addition of a new business partner. According to the Rabbinate supervisor, the partner could not be trusted because he was Russian.

The owner emphasized that he was not interested in fighting with the Rabbinate. He described himself as a peace-loving person. His goal, he said, was simply to understand what his customers actually wanted.

If the certificate is meaningless, he asked, why should it matter? Why shouldn’t customers trust him when he says the restaurant is kosher?

The Public Reacts

The responses came quickly. Many commenters criticized the Rabbinate, accusing it of corruption and unnecessary demands. Others questioned why the owner had bothered with a certificate in the first place. Some even encouraged him to open on Shabbat.

To his credit, the owner made it clear that the restaurant would always remain closed on Shabbat. Shabbat, he wrote, belongs to his family.

Still, his doubts about kashrut remained, especially after a journalist turned the Facebook discussion into a local news article. Claims of unreasonable supervision and alleged discrimination make for an easy headline.

A Crucial Detail Emerges

Among the commenters was a former spokesperson for the Rabbinate. At first, he responded in general terms. He acknowledged that complaints about local rabbinates are common, including in Jerusalem. But he pointed out a consistent pattern.

In most cases where a business owner claims sudden, arbitrary demands, something has changed in the business. It could be a new menu, new staff, or a new partner. Trust, he explained, is not only practical but halachic. In many cases, serious kashrut problems were discovered.

Later, he addressed the specific situation. The new partner, it turned out, also owns a non-kosher establishment. The Rabbinate was concerned that non-kosher products might be transferred between businesses, which requires stricter supervision. In addition, the partner brings alcoholic beverages into the restaurant.

This led to a long discussion about a little-known halacha: wine opened by a Jew who publicly violates Shabbat is not kosher. Many Israelis are completely unaware of this law.

“Trust Me, It’s Kosher”

None of this seemed to change the owner’s direction. He later posted an update thanking everyone for their input and announcing his decision to work with a private kashrut organization. Eventually, he added, customers would be expected to rely on his personal assurance that the restaurant is kosher.

So if there’s a bug in the cake, what’s the big deal?

Why Personal Trust Is Not Enough

With all due respect to the owner’s Shabbat observance and his sincere intentions, most observant Jews will no longer eat at his restaurant. From his own words, it seems he understands this reality, but not the reason behind it.

Why do people trust a certificate more than a well-meaning owner?

I once attended a discussion where several secular women expressed frustration that religious guests refused to eat in their homes, even though they “keep kosher.” They explained that they separate milk and meat and buy only products with kosher certification.

An older religious woman then asked them a few simple questions. It quickly became clear that two of them never sifted flour. One had never heard of insect-free produce. None knew that cutting an onion with a meat knife makes the onion meaty.

Kashrut is complex. Running a private kitchen is simpler than running a commercial one, but even at home, real knowledge is required.

Kashrut Requires Expertise

How can one rely on someone who does not know that eating an insect is considered more severe than eating pork under Jewish law? How can one eat in a home where people believe that kashrut only means separate dishes and not cooking meat and milk together?

In restaurants, the issues are far more serious. As the former Rabbinate spokesperson noted, most people have no idea that opening wine by a Shabbat violator renders it non-kosher. Yet that is the law. A business owner who is unaware of this misleads customers, even if he is fully convinced that his establishment is “completely kosher.”

The Certificate on the Wall

There is a well-known Jewish joke about a haredi man who enters a restaurant and notices that the kosher certificate has expired.

“And don’t you trust me?” the offended clerk asks, pointing to a picture of a famous rabbi on the wall. “Look who my grandfather was!”

The customer sighs and replies, “I would feel more comfortable if your picture was on the wall and your grandfather was here selling.”

Today, great Torah scholars do not usually run restaurants. In their absence, good intentions, warm feelings toward Judaism, and Shabbat observance are not substitutes for a reliable hechsher.

Even complete personal honesty is not enough. To say “Trust me, everything is kosher,” we must first be certain that the person truly knows what is kosher and what is not.

עברית

עברית