Magazine

Echoes of Survival: From the Holocaust to Hope

Professor Daniel Gold, former Air Force pilot and senior scientist at Tel Aviv University, reflects on survival, the Holocaust, and the trauma of October 7

- Hidabroot

- |Updated

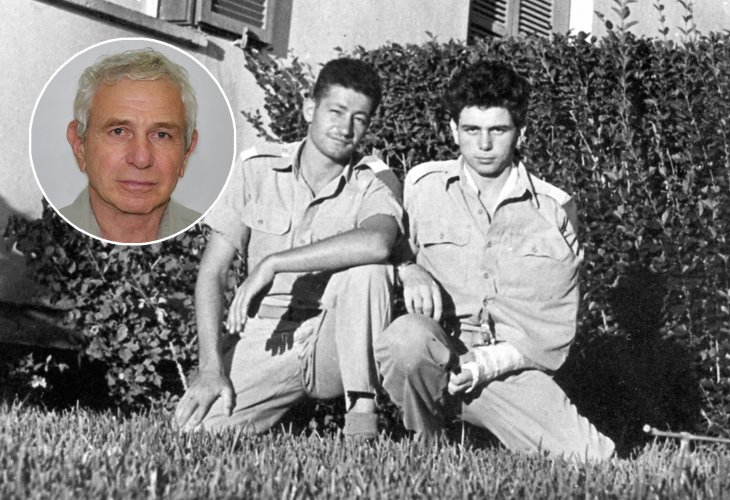

(Inset: Daniel Gold)

(Inset: Daniel Gold)The year is 1943. The Shavli Ghetto in Lithuania.

Six-year-old Daniel Gold is in a narrow room in one of the ghetto apartments, together with his parents, relatives, and six young cousins, all roughly his age, the youngest only two years old. By a miracle, they had managed to survive the horrific wave of killing and slaughter that ravaged Lithuania in those years, but it was clear that it was only a matter of time before the ghetto would be “cleansed” of small children, just as the elderly had already been taken away before them.

“It was a time when our parents went out to work every day,” shares Professor Daniel Gold, today 86 years old, “and we children stayed in the apartment in the ghetto, under strict orders not to make a sound and not to leave the house. We waited with bated breath for our parents to come back, and only in the evening would we see them. They tried to bring us a bit of food – bread or a thin, watery liquid called soup, sometimes rotten potatoes, the worst kind. We were all terribly hungry and would pounce on whatever they brought like someone who’s found great treasure.”

The only photo from before the war, with cousins

The only photo from before the war, with cousinsBut one day, the terrifying news everyone knew would come finally arrived: the Germans had come, and they were going house to house, taking all the small children under the age of 13 who were not considered “useful” for work.

“It was in the morning,” Professor Gold recalls. “My mother and my aunt Leah were still inside the house, but from the commotion outside they understood what was about to happen. Without thinking much, they opened the hatch to the cellar under the kitchen floor and shoved all seven children in the house down into it. The space was so narrow that we were crushed against one another, unable to move, but they warned us not to make a sound and explained: ‘There are evil people outside who want to kill you. You must be quiet. You may not even whisper or cough. Stay silent until we open up again and take you out.’

“They closed the cellar door – but at that moment little Simcha, the two-year-old, burst out crying. My aunt opened the cellar again, pulled him out, climbed up to the attic, and hid there with him in the furthest corner behind a piece of furniture. In the memorial pages she wrote years later, Leah described how she clutched her child with all her strength to her chest until he stopped crying – and didn’t cry again for all the hours that followed.

“Meanwhile, my mother, the hero, sat down at the table, after covering the cellar with pieces of cloth, and received the Ukrainians – the German collaborators – who entered the house to take the children to the death transport to Auschwitz. We heard their boots, the scraping of furniture. We heard them arguing and shouting at my mother, but we didn’t understand her replies because she spoke in Russian and we only knew Yiddish. To this day, I don’t understand how she managed to convince them there were no children in the house. But in the end, when the Germans left, my mother let us out of the cellar. We were alive, but half fainted from lack of air, suffocation, and having no food or water. My mother and aunt washed us and put us to bed, but with that, childhood life in the ghetto effectively ended. There were practically no children left in the Shavli Ghetto – except the seven of us.”

Life Under the Floor

Professor Gold takes a deep breath. It’s clear he remembers every detail of what happened. Even though so many years have passed, and today he lives in Israel and is considered a senior scientist and researcher in the medical world, as well as a retired Air Force pilot, the events have never left his memory.

“I was born in Lithuania,” he continues. “We lived in the city of Shavli together with thousands of other Jewish families. We were a large extended family – my mother originally had eight brothers and sisters, my father had four. Some of them immigrated to Israel in the 1920s and ’30s. Sadly, many family members did not survive the war, including my grandparents. But if we look at the half-full glass – I survived, my father survived, and so did six of my cousins and my aunt. We were almost always together. We went through the war together in ways that are beyond imagination – small children in the most dangerous places, right under the Germans’ noses.”

About the city of Shavli, he says: “The Germans entered officially in 1941, but even before that there was a terrible killing spree carried out by local Lithuanians. Groups of youths walked through the streets with cold weapons – axes and hammers – pulling Jews out of their homes and murdering them. Once the Germans took over the city, the more ‘organized’ killing began: they took about 2,000 Jews out of the roughly 7,500 Jews who lived there and slaughtered them in the forests without mercy.”

And what happened to you during those days?

“At that time we were still together with our grandparents and cousins. Our parents gathered us all and made it very clear we had to be extremely careful. Even if we heard shouting outside or orders to come out, we were not to open the door under any circumstances.

“We absorbed this deeply, and when there was a knock at the door the next day, no one opened it. Only later did we understand how wise that was, because at our neighbors’ home, where the door was open, a real pogrom took place – and the same happened to many Jewish families in the area.”

But at the next stage, they could no longer escape the shared fate of the Jews of the city: all Jewish residents were ordered to move into the ghetto.

“Our apartments were given to Lithuanians,” Professor Gold says, “and we were crammed into the ghetto apartments – one family per room. We were in an apartment where our cousins also lived.”

Volunteering in the police

Volunteering in the policeWhat followed was even more horrifying than anyone could have imagined.

“A week after the ghetto was sealed, the Germans murdered all the children in the orphanage because they were ‘useless eaters’ and had no one to care for them. Then they emptied the ghetto of all the elderly, and we said goodbye to the grandparents we loved so much. We never knew exactly what their fate was, but only later did we understand there were hundreds of mass graves all over Lithuania.

“The Lithuanians cooperated closely with the Germans. They were the ones who gave them names, reported exactly how many people were in each family, and where they lived. For two and a half years we continued to live in the ghetto. We had, so to speak, ‘quiet,’ but of course it was anything but a normal life.

“We were always hungry. My mother tried to add water to the dry bread to puff it up a little, but that only caused us diarrhea and stomach pain. The soup they gave us was not filling at all – mostly lukewarm, dirty water with almost no vegetables. From time to time, our parents tried to smuggle in food from Lithuanians who cooperated and gave them groceries in exchange for clothes or jewelry, but that was very dangerous and not always possible.”

And how did you spend your days? What did you do with all those long hours?

“Of course we had no schools in the ghetto. No formal classes, no kindergarten. In the evenings, when we finally met our parents, we would all sit together and talk, and each time we spoke longingly about Eretz Yisrael – how good it is there, how everyone is free, how warm and pleasant it is. Even then, a strong desire to go to the Land of Israel started growing inside me.”

In 1943, as mentioned, the ghetto was emptied completely of children, and only the seven Gold cousins remained.

“We stayed alive,” Professor Gold says, “but it was clear we could not leave the house, not even for a moment. It was a matter of life and death. For seven months we were locked inside the room, keeping absolute silence, shut in.

“I remember desperately longing to see the big lake, to see the sun, to see the planes we heard flying overhead. I envied anyone who could go outside. And it was freezing. When our parents went out to work, they didn’t heat the house – so no one would suspect there were children there. The cold went straight into our bones. It was terrible.”

Certificate of Appreciation

Certificate of AppreciationTwenty-Three Hours Without Moving

In the summer of 1944, as the Russian army advanced from the southeast toward the northwest, the Germans realized that the end of the war was approaching. Wanting to “finish” what they could, they decided to liquidate the Shavli Ghetto – meaning to march everyone who remained there to execution pits in the forests.

“The ghetto residents heard about this and understood what it meant,” Professor Gold relates. “Everyone wanted to escape, but to do that, you needed someone on the outside, on the Lithuanian side, who would take you in. My uncle and aunt worked very hard to find someone who would help. In the end, my father located a farmer about 70 kilometers from the city who agreed, in exchange for payment, to house my uncle and aunt, their daughter, me, and a neighbor who joined us.

“My parents didn’t come, because the farmer refused to take them too. So they stayed in the ghetto and hoped to find another place. They never did. In the end, everyone left there was deported to the Stutthof concentration camp near Gdansk in Poland. Shortly afterward, the men were separated from the women and sent into a network of camps centered around Dachau.

“We were taken to the farmer’s homestead. He gave us fresh bread, and to this day I remember the sweet, special taste – after three years without real food. Then he pushed us under the floor of his house, where there was a small hidden space behind logs and a sheet. The space was very low, so we had to lie down all day. Only at night were we allowed to go out for a few minutes to stretch, go to the toilet, wash our faces and hands, and get dinner.

“We were so tightly packed in the hiding place that if one person needed to turn over, all of us had to turn too so that he could move. We were of course forbidden to speak out loud – only to whisper. I was already seven years old then, and to this day I don’t understand how we managed to lie there for 23 hours at a time without moving, without eating, without going to the bathroom, in total darkness and with almost no food. When I look at my grandchildren today at that age, full of energy and potential, I think of how we were like paralyzed, physically and mentally. And all the while I missed my parents terribly, thinking about them constantly and worrying about them.”

In November 1944, the Russian army reached the area where the family was hiding.

“I remember the Lithuanian farmer shouting to us from inside the house: ‘The Russians are coming, you can come out!’ But we didn’t trust him. My aunt crawled out first and looked at the soldiers’ uniforms. Only when she was absolutely certain they were Russians and not Germans did she approach one of them and say we were Jews who had escaped from the Nazis. The Russian soldier replied: ‘That’s impossible. The Nazis killed all the Jews. If you’re alive, you must have collaborated with them.’

“It took her a long time to convince him we really were Jews who had fled the ghetto.”

And that’s how you were freed?

“Yes. After years of war, we could finally go out into the open air without being afraid of being killed. The transition was so sharp – one day we were hiding under the floor, fearing for our lives; the next day we could walk around outside as much as we wanted.”

Dreams as High as the Sky

After the war, Professor Gold returned with his aunt, uncle, and cousins to the Shavli Ghetto area, and only then did they understand that nothing was left of it.

“The entire city was destroyed and bombed,” he says. “But luckily, we met a Jewish family whose house was still standing, and they gave us a room. At last we had a roof over our heads, and my uncle began working and earning money. So we started to build a new life – at least on the surface. But very quickly we learned the unimaginable: out of 7,500 Jews in the city, only about 500 survived.”

And what about your parents?

“Of course, I constantly wanted to know what had happened to them. Together with my uncle and aunt, we tried to find information and discovered that they had been sent to the concentration camp together with other men from the ghetto, including relatives of ours. Most of the men in my family did not survive, but my father – whose finger had been severed while working in the ghetto – managed to survive Dachau and was liberated by the American army. Sadly, I never saw my mother again.”

During that time, survivors from all over Lithuania began to arrive in Shavli in search of relatives, and from them Professor Gold heard that his father was alive in the western, liberated part of Germany.

“It was clear to me that I was going to see him,” he recalls. “After a long journey with my aunt and uncle to Germany, I met my father at the train station. It turned out, to my great excitement, that he had been waiting there for weeks, watching the trains arriving from Poland, hoping to find me. That’s how we met after two and a half years apart – and finally we were together again.”

In the next period they lived in a Jewish community in Munich.

“Physically, our situation was relatively good,” Professor Gold says, “but the desire – especially mine – to go to the Land of Israel never left me. For three years I studied in a local school in Munich with teachers, some of whom were from Israel, and I just dreamed about the day we’d move there. My father worked and earned well, and he was getting attractive offers to move to Switzerland or Canada, where we could have lived a comfortable life. But I did not want to give up my dream.

“At a certain point I told my father I didn’t want to keep studying in Munich – I only wanted to go to Israel. That tipped the scales, and the dream came true: we immigrated to Eretz Yisrael.”

Working in the lab

Working in the labProfessor Gold arrived in Israel at an age that matched 10th grade, but in reality he had only six and a half years of schooling. Even so, he insisted on studying and succeeding, and eventually was accepted to the Air Force pilot course. He served in the Israeli Air Force for 35 years, including during the Six-Day War, the War of Attrition, and the First Lebanon War.

“It was important to me to push and reach as high as possible, in every sense,” he says with a smile. “Even the sky wasn’t the limit.”

From Powerlessness to Determination

In these days of war, Professor Gold cannot avoid relating to the current situation.

“As someone who was a career officer and pilot for many years, I can say that no victory ever came easily. In every war, we had to pay a very heavy price. Personally, I went through a very difficult experience when a close friend accidentally shot me, and I spent almost a year wounded. But throughout that time I taught myself to focus on what really matters – to set clear goals and carry them out, to strive to do everything in the best way possible. I see our young people today, filled with purpose, and I believe in them deeply. That is the path to victory.”

Holocaust survivors often say that the massacre on Simchat Torah brought them back to the war years they so wanted to forget. Do you feel the same?

“Over the years, I’ve given lectures at Yad Vashem and around the world – in synagogues and universities. Each time, I show the photo of me as a child during the war, a humiliated, frightened boy – and then a photo of me in an Air Force squadron. For me, these two images represent the extremes of my life story.

“Now, when I see the images of our dear IDF soldiers being overrun and the humiliation they suffered on that terrible day, it pains me to the depth of my heart.

“The feeling of helplessness I experienced as a child in the Holocaust – when the Ukrainian thugs were above us and we were fleeing in terror to the cellar – comes back and floods me again. I can probably imagine more than most people what it felt like to sit inside a safe room while the murderers are just beyond the wall, waiting for a chance to get to you. The only difference is that this isn’t 1943 – it’s 2023. And it’s not happening in Europe, but inside my own country, the one I wanted so badly to reach, and that I was so proud of. All this creates a very painful mixture of feelings inside me.”

And yet, Professor Gold emphasizes that he tries to remain optimistic. “I believe that with God’s help we will still come out of this, that we will continue living in our land for many years, and that I myself will live to see the horizon looking clearer again – in the very near future.”