Magazine

Uncovering the Hidden Torah of the Lubavitcher Rebbe: Rabbi Chaim Shaul Brook’s Life Mission

how one Chabad scholar is still revealing the Rebbe’s teachings and vision of global redemption decades after his passing

- Yossi Saidov

- |Updated

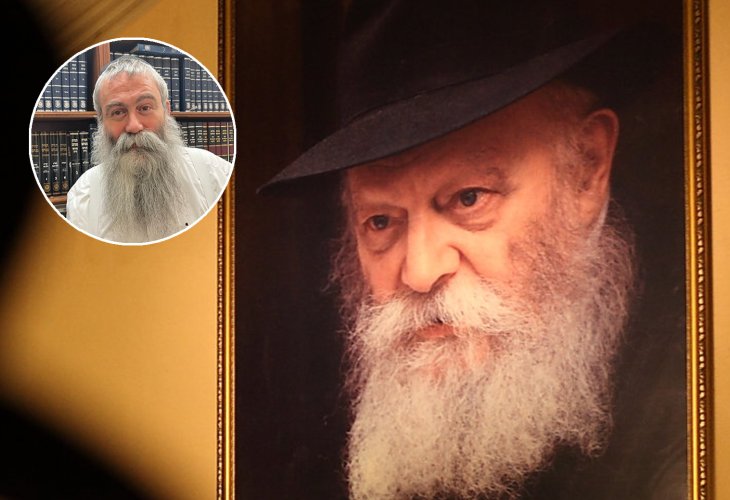

Inset: Rabbi Chaim Shaul Brook (Background photo: Yaakov Nahomi / Flash90)

Inset: Rabbi Chaim Shaul Brook (Background photo: Yaakov Nahomi / Flash90)It was four in the morning, and Rabbi Chaim Shaul Brook couldn’t sleep. His thoughts kept circling back to a page written over fifty years ago, in a tight handwritten script in a notebook he had been trying unsuccessfully to decipher. The first half of the page looked like it had been written in a normal, continuous way. But from the middle of the page onward, the words no longer seemed to connect. He managed to read each line, but there was no clear connection between them.

Rabbi Brook is a Chabad chassid and the publisher of the teachings of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, whose yahrzeit the Jewish world marked on the 3rd of Tammuz. The densely written page that was keeping Rabbi Brook awake was in the Rebbe’s own handwriting. After the Rebbe’s passing, three black notebooks were found in the drawer of his desk, written in small, neat script — notes he had written for himself before he became the seventh Rebbe of Chabad. These notes, some of them personal journals, were written by the Rebbe for his own use: outlines, Torah talks of his, and also diary-like records of the words of his father-in-law, the previous Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn. A group of Torah scholars works each week on pages from these notebooks, trying to decipher and publish them for the Rebbe’s chassidim.

Preparing for Redemption

At four in the morning, Rabbi Brook suddenly jumped out of bed. He got dressed, hurried over to his office, turned on the computer, and tried to approach the Rebbe’s handwriting in a different way. The first half of the page could be read in the normal order. Then he noticed a small line to the right of the middle row. Rabbi Brook skipped down to the last line and began reading the page from the bottom up. Suddenly, the words made sense, the lines connected, and the text the Rebbe had written for himself decades earlier became understandable for his followers as well.

Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson is one of the figures who most shaped the face of Judaism since the second half of the twentieth century. He was born in Ukraine in 1902 to his father Rabbi Levi Yitzchak and his mother Chana. After several years in cheder and Talmud Torah, he went on to learn from his father, who served as the chief rabbi of the city of Yekaterinoslav.

He married the daughter of the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, studied in the universities of Berlin and Paris between 1929–1939, and after the Nazis conquered France, he managed to escape and reach the United States in 1941. A year after the passing of his father-in-law, on the 10th of Shevat 5711 (1951), he accepted the pleas of the chassidim and took on the role of the seventh Rebbe of Chabad. Upon becoming Rebbe, he defined his life’s mission: to hasten the Redemption and to turn his generation into the last generation of exile and the first generation of Geulah.

He is widely known as the Rebbe who handed out dollar bills for charity to those who came to see him, who sent emissaries (shluchim) to remote corners of the world, and whose chassidim work to help Jewish men put on tefillin and Jewish women light Shabbat candles. But his vast Torah world remained mostly hidden, accessible mainly to his chassidim and to those familiar with his works.

Even today, years after the Rebbe’s passing, not all of his Torah has been published. His followers are still putting out his talks. The Rebbe would deliver sichot — talks, Torah ideas, guidance, and directions on how to act and what to do, to his chassidim. He began giving these talks at the start of 1950 (Shevat 5710), after the previous Rebbe’s passing, and continued until he fell ill in March 1992 (27 Adar I 5752). For 42 years, the Rebbe spoke talks and maamarim (formal Chassidic discourses) to his chassidim on Shabbat, holidays, and special days — reaching tens and hundreds of talks each year.

Most of his words were documented by the chassidim: at first in writing, and through “chozrim” — chassidim who could repeat his words by heart, word for word, on Motzaei Shabbat. Over the years, the chassidim began recording the Rebbe on weekdays as well, and from the early 1980s they even started videotaping him.

This extensive documentation means that a large part of the Rebbe’s words has been edited and published: at least four volumes for each year. In addition, the Rebbe left behind tens of thousands of letters that he sent to anyone who wrote to him. Many of these are published in the series Igrot Kodesh, which so far documents his letters up until the mid-1970s. His letters in English have not yet been systematically translated and published, and the Rebbe’s flowing wellspring of Torah and guidance continues to be inexhaustible even almost thirty years after his passing.

“There’s no doubt that the Rebbe had a plan to transform the entire world for the good and to prepare it for the Redemption, literally,” says the man responsible today for publishing the Rebbe’s recorded talks, Rabbi Chaim Shaul Brook. “It’s really a pity that the broader religious and chareidi public doesn’t fully grasp the Rebbe’s genius in Torah. The Rebbe’s life was basically the Torah. Everything he did flowed out of Torah. There wasn’t a free minute when he wasn’t learning Torah.”

Rabbi Brook does this work from a small, crowded room on the top floor of the Chabad World Headquarters building, adjacent to 770, the Rebbe’s famous shul at Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn, New York.

(צילום: דוד כהן / פלאש 90)

(צילום: דוד כהן / פלאש 90)Meaning in Every Word

Speaking with him is fascinating. On his computer screen he opens scanned images of the Rebbe’s handwritten pages; from the drawers beside his desk he pulls out yellowed notebooks containing written records of decades-old talks; from time to time he jumps out to the hallway or to the next room and brings back one of the printed volumes of the Rebbe’s sichot.

He was born in Jerusalem in 1967, the youngest child in a Chassidic family that traces its roots back to the chassidim of the first Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, author of Tanya.

His first personal meeting with the Rebbe was when he was nine years old. At home and in his cheder, they spoke Yiddish, and that was also the Rebbe’s mother tongue. “I came to the Rebbe before Shavuot and went in for yechidut (a private audience) with my mother. When we went in, the Rebbe asked my mother to sit down once, twice, but she kept standing, and then he began to speak to me.

“The Rebbe asked me where I study, who my teacher is, what I’m learning and asked questions about the chapter of study for about five minutes. The Rebbe opened the drawer, took out a dollar—this was a time when there still wasn’t a regular ‘dollar distribution,’ gave it to me and said: ‘Because you knew (your learning), I’m giving you a dollar for tzedakah in Eretz HaKodesh.’ Then he took out of the drawer 100 Israeli lira, a big bill with Herzl’s picture on it, gave it to my mother and told her to give it to charity in Eretz Yisrael. And that was the end of the yechidut.

“In Shevat 5739 (January 1979) we came again to the Rebbe. Again, the Rebbe asked what I’m learning and tested me for about eight minutes. The 13 minutes that the Rebbe dedicated to me from his precious time — I’m still ‘paying’ for them to this day, and I haven’t finished paying. I have to ‘repay’ the time he gave me.”

At that time, there was a new project running in 770: a broadcast center that transmitted the Rebbe’s farbrengens by telephone to Chabad communities worldwide. “From the age of eleven and a half I went to hear every broadcast of the Rebbe. It was at three-thirty or four-thirty in the morning. We would go to the yeshivah, the whole yeshivah would gather, and we would listen to the Rebbe’s talk. I was a kid; I understood the language, I understood the simpler parts.

“When I was already in yeshivah, one of the teachers, Rabbi Menachem Wilhelm, asked that before the shiur each boy say something he had heard from the Rebbe in the broadcast. My turn came, and since I liked to make things lively and cause a bit of noise, I said that the Rebbe said anyone who needs to say berachah acharonah (the after-blessing on food) should say it. (The Rebbe would remind the crowd to say a concluding blessing at the end of the talk.) Of course, the whole class burst out laughing, but the rabbi was an educator of the highest level. He said to the class: ‘What are you laughing at? This is something the Rebbe says all the time, and everything the Rebbe says is important.’ My whole attitude to the Rebbe’s talks changed. I understood that every remark and every word has meaning and significance.”

Rabbi Brook visited the Rebbe’s court several more times in the early 1980s. At age 18 he came to learn in the central yeshivah at 770, and since then he has been there. He started at the bottom: taking printed pages to the bookbinder, typing up the recordings of the Rebbe’s talks, making coffee and sandwiches for Rabbi Yoel Kahn, the Rebbe’s chief chozer who edited his maamarim, bringing him sefarim he asked for, helping him write — and slowly, he joined the team that edited the Rebbe’s sichot. Today, as mentioned, he heads the official Hebrew-language publication of the Rebbe’s Torah.

“The Rebbe said 1,568 maamarim of Chassidus. 453 of them were missing and hadn’t been written up. Around 200 of those were in audio recordings, others existed in handwritten form. Many of the Rebbe’s farbrengens continued for hours after Shabbat or Yom Tov ended. Yeshivah students would make havdalah immediately, and then they would write down what the Rebbe had said while it was still fresh. Dozens and hundreds of the Rebbe’s talks were recorded that way, and our work is to track down all these documents, edit them, and publish them. Many of the “missing” maamarim were found in those notes. Today only 31 maamarim are still missing — and I’m not giving up.” The search work spans the globe.

(צילום: אריה לייב אברמס / פלאש 90)

(צילום: אריה לייב אברמס / פלאש 90)11,000 Hours of Talks

Rabbi Brook explains that the Rebbe himself was involved in how his Torah was recorded. He guided the writers on how to prepare the sichot for publication: first to learn the sources of the talk, then to edit the text so it would be suitable for written study and not just be a raw transcript of spoken Yiddish.

“The Rebbe’s Torah is contagious. Once you start learning it, you can’t leave it. I once listened to a recording of one of the Rebbe’s hadranim (siyum/“completion” talks, often with deep explanations) during a long car ride. I reached my destination at one-thirty at night, and I just couldn’t get out of the car. I felt I had to stay until the end. When you’re in a state like that, you realize the Rebbe has ‘grabbed’ you. And every time I learn a sichah or a maamar of the Rebbe, I find something new in it.”

The scope of the Rebbe’s teachings is unprecedented in Jewish history. There were 1,907 farbrengens, 1,286 sichot — talks of Torah and guidance to his chassidim — altogether more than 11,000 recorded hours.

“Maamarim are Chassidic discourses based on Kabbalah. When the Rebbe said a maamar, everyone stood; the Rebbe’s eyes were closed, there was a handkerchief wrapped around his hand — it wasn’t a regular event. Sichot can be about current events, explanations on the date in the Jewish calendar, explanations of words of Chazal, and so on.

“For 15 years, the Rebbe said sichot every Shabbat in which he explained Rashi’s commentary on the weekly Torah portion. He began these talks after his mother passed away in 1965. Starting in 1970, the Rebbe began focusing on his father’s commentaries on the Zohar and also worked through his father’s commentaries on the Tanya. In the summer months, he would speak about Pirkei Avot,” and also about the daily study cycle in Rambam.

The Rebbe wove together the revealed Torah — Talmud and halachah, with Kabbalah and Chassidus. “On the yahrzeits of his father, his mother, and the previous Rebbes of Chabad, he would give a hadron, a siyum on one of the tractates of the Talmud. Sometimes the hadron was on the entire Talmud. The Rebbe’s hadronim would sometimes continue over several talks in a row. Altogether there are 174 hadronim of the Rebbe, 18 of them on the entire Talmud.

“The Rebbe had a method: usually he connected the end of the tractate to its beginning. He would question the text of the Talmud and show how the revealed part connects to the inner dimension of Torah. This is something he learned from his father. For example, in the hadron on Masechet Makkot in 1965, the Rebbe examines Rabbi Akiva’s way throughout Shas: why does Rabbi Akiva laugh when the other sages cry at the sight of the destruction? What is Rabbi Akiva’s approach to the world? What is his method? You see this in the inner meaning of things.

“In the last decade of his leadership, the Rebbe established the daily Rambam study cycle and gave an annual hadron on the Rambam, connecting the first halachah in Mishneh Torah to the last. In addition, there are the Reshimot — the Rebbe’s personal notebooks found in his desk drawer, and on top of that there are 39 volumes of Likkutei Sichot, edited talks of the Rebbe on the weekly Torah portion, all of which passed through his review and approval. And of course, there are the Igrot Kodesh — 33 volumes of the Rebbe’s letters that have been published so far, with more still coming out. There’s no topic he didn’t touch there: medicine, education, shalom bayit, livelihood, running institutions, everything. It’s all there; you just have to find it. And no one has even really started on the Rebbe’s letters in English. There you’ll find many things that speak to the wider world. The Rebbe corresponded with doctors, professors, and went into great detail.”

(צילום: shutterstock)

(צילום: shutterstock)Redemption

The Rebbe saw every person as a partner in the vast mission he had taken upon himself: hastening the redemption of the Jewish people and the coming of Mashiach. He was the first Jewish leader to speak to the nations of the world and ask them to adopt the Seven Noahide Laws.

“The Rebbe quoted many times the Rambam’s words that the nations of the world are obligated to keep the Seven Noahide Laws they were commanded, and he asked that this be publicized in their language and that people influence them to keep them, so that the world will be a better world.”

The Rebbe never moved to Israel and never visited it, and this was his reasoning: “The captain is the last to leave the ship,” and as long as there are Jews living in exile, he would remain with them. Even so, Rabbi Brook explains that the Rebbe saw Eretz Yisrael as a holy land and sent emissaries from abroad to settle there. He opposed giving up territory in exchange for peace, for reasons of pikuach nefesh (danger to life).

“According to halachah in Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chaim 329: if non-Jews surround a Jewish town, Jews must go out against them with weapons even on Shabbat. And it is forbidden to hand over even one inch of Eretz HaKodesh. And if they (the nations) come with claims, all we need to tell them is the words of Rashi in his opening comment to the Torah: that if the nations say ‘You are robbers, for you conquered the land of the seven nations,’ we answer them that ‘the whole earth belongs to the Holy One, Blessed be He. He created it and gives it to whomever is right in His eyes. In His will He gave it to them, and in His will He took it from them and gave it to us.’”

As a boy in Jerusalem, Chaim Shaul Brook had to get up in the middle of the night and know Yiddish just to hear the Rebbe’s voice coming from across the ocean. To actually see him, he had to board a plane and fly to New York. Today, the Rebbe’s teachings are spread daily in short video clips on social media. Tens of thousands of people consume his Torah every day with subtitles in many languages. A huge project of preservation keeps the Rebbe’s teachings alive and accessible for future generations.

How do chassidim continue to function without a Rebbe physically present?

“When the Rebbe took on his position, he already had a plan: to prepare the world for Geulah. In the first decade there were only about sixty shluchim. In the next decade, 130. In the following one, already 500. Since the Rebbe’s passing, the number of shluchim in the world has doubled, and today there are nearly 6,000 emissaries in 102 countries. How is that? That was the Rebbe’s plan.

“It takes time to build a building. It takes time to bring the Redemption. Today you see Chabad chassidim who were born after the Rebbe’s passing getting on planes and going over to Jews with the offer to put on tefillin. My children are much stronger than I am; I look at them and I’m amazed. Everywhere. It’s in their blood. The Rebbe changed the world.”