Magazine

From Amsterdam to Israel: How Antisemitism, Identity, and Faith Brought Oded Nir Home

After 19 years in the Netherlands, a successful international music career, and a violent antisemitic wake-up call in Amsterdam, musician Oded Nir explains why he cut ties with Europe

- Hidabroot

- |Updated

In the circle: Oded Nir

In the circle: Oded NirHours before the lynch attack in Amsterdam — an incident that took place about a year ago against Israeli soccer fans who had arrived in the Netherlands to support their team — Oded Nir already had a strong sense that something was off. Having lived there for 19 years, he noticed the graffiti condemning the “massacre in Gaza” and the hostile stares. That violent event led him to make a final decision to sever his long-standing connection with the Netherlands. A few months later, he left his international music career behind and immigrated to Israel.

“4,000 Applicants for One Class”

Nir is 50, married, and today lives in Rishon LeZion. “I was born in Tel Aviv, into a secular home. As a child, we lived across the street from Menachem Begin’s home. The Border Police officers guarding his house used to give me chewing gum.”

When he was in third grade, Nir appeared in a Tu B'Shvat school play. Someone noticed his dramatic talent and was impressed. Around that time, the School of the Arts was opening its very first year, and his parents decided to take him to the entrance exams.

“There were 4,000 applicants for one class — completely insane,” he recalls.

Young Nir passed the exams and was among the few accepted.

“The elite of the elite of Tel Aviv studied there — children of all kinds of famous figures. I studied music, acting, and art.”

Growing Up Secular, Searching for Something More

The home he grew up in, as noted, was far from Torah observance. Nir explains that the family maintained a loose but respectful connection to Jewish tradition. “I didn’t know what kiddush was, but we would go to synagogue for Kol Nidrei on Yom Kippur night. Afterwards, we’d go home and eat — but not out of defiance. I remember my father telling me, ‘Don’t eat outside.’”

The first change in him came on the eve of his bar mitzvah. “I went to a class to prepare for it and came home a little different,” he recalls. “Suddenly I refused to eat the Shabbat cholent because it had pork in it. From my bar mitzvah onward, I put on tefillin every day, and I remember hiding a picture of the Lubavitcher Rebbe under my pillow.”

How did your parents react? I imagine it was unusual in the environment you grew up in.

“It was unusual — especially in the 1980s,” Nir agrees. “But they didn’t say anything negative. Mostly, they were disappointed. My mom was really upset that I ruined her cholent,” he laughs. “My older brother, who was 28 at the time, followed my lead and also became careful about these things — so pork no longer entered the house.

“On the other hand, once I tried to make a sandwich with white cheese and sausage, and my father immediately said, ‘Those aren’t eaten together.’ He didn’t explain why, but mixing meat and dairy just didn’t sit right with him.”

Another moment that stuck with Nir occurred in a Bible class at school, when he asked the teacher why they were studying Torah with uncovered heads. “The teacher said that anyone who wants to wear a kippah can. At the next Bible lesson, I showed up wearing one. Four other boys joined me, but over time they dropped out. No one wants to be different — especially in a secular school.”

Alone in a Foreign Country

Alongside his high school studies, Nir invested heavily in drama and, as a teenager, appeared alongside some of the biggest cultural figures of the time. Among other roles, he participated in the play Sallah Shabati, playing Nissim, Sallah’s son.

At 15, he decided it was time to change direction and enter the world of rock music. “I started learning guitar and bass in Tel Aviv, going to clubs and parties. At the same time, I still put on tefillin and kept kosher food. A life of contradictions.”

Over the next 15 years, Nir continued to develop and build a rich musical background. “For years I was Yitzhak Klepter’s bass player — one of the founding fathers of Israeli rock. I toured with him all over the country. I also played in many Israeli rock bands and composed music for theater.”

Despite his professional progress, Nir had a clear ambition:

“I wanted to break through as a solo artist. In 2006 I flew to the Cannes Festival, and there I received a contract from a Dutch record label.”

The offer was tempting, and he decided to go all in. At 30, he left his work in Israel, packed his belongings, and moved to Amsterdam.

“The contract collapsed after three weeks when it turned out the label had gone bankrupt. After I got off the plane, I discovered I’d become someone who didn’t even have money to buy me hummus.”

Despite the shock and loneliness, Nir didn’t give up on his dream. He stayed in the Netherlands and rebuilt himself from scratch.

“When you arrive in a foreign place, you have to be better than others to succeed. I realized I was surrounded by musicians, and only if I were unique and authentic would there be a reason to notice me. The Jewish mind invents solutions in situations like that.”

He developed a unique genre in which he stands on stage while simultaneously DJ-ing and playing bass.

“The Ego Starts to Crumble”

Over the years, Nir became a well-known musician abroad. When asked where and for what audiences he performed, he spends long minutes detailing the genres and stages. Among other things, he worked as a DJ in luxury hotels and performed on major stages for audiences of up to 25,000 people.

“I performed all over the world — from China to Malta, London, Italy, Paris, Sardinia, and more. To date, I’ve released three solo albums. For the past five years, I’ve worked closely with Derrick McKenzie, the drummer of the legendary Jamiroquai from the early 1990s. I’ve also owned a record label for 15 years, which has released over 120 albums by artists. I had the opportunity to work with wonderful people.”

Beyond the impressive career, how did you experience everyday life in the Netherlands?

“I’ve thought about that question a lot in recent years. I was so driven to fulfill myself that I forgot to live. That doesn’t mean I had a bad life — I lived my self-fulfillment.

“But in the end, I wasn’t living in Israel. I missed daily contact with close friends, and I also didn’t have the option of meeting Jewish, Israeli women.”

Nir notes that although he married around age 47, it was important to him to marry a Jewish woman. “There was a period when I broke down and dated non-Jewish women, but I didn’t find myself with them. I felt it only lowered me spiritually and emotionally.”

He describes a growing gap between his musical fulfillment and his personal life. “I reached a state of very severe imbalance between the personal and the professional. The professional side kept rising, and the personal side kept falling. At some point, what holds you up is ego — but ego can’t carry you through an entire life. Ego can take you very high and then smash you headfirst from above. Without faith, and without personal balance with a wife and a home, the ego starts to crumble.”

You don’t sound like someone with a lot of ego.

“Over the years, I went through several extreme situations. They made me understand who and what I am — and that I’m not that important. People who knew me eight or nine years ago would say I was full of ego.

“In addition, over the past six months, since returning to Israel, I’ve entered a kind of mission for the Jewish people. That mission also lowered my ego. I understand that you and I are talking now because of the message — not because I’m ‘the interesting artist.’ It wasn’t my music that brought us to this conversation.

“Faith keeps you grounded,” he adds. “I always preferred working with people of faith. They live knowing there’s someone above them, that they aren’t the center. Of course, most of the people I worked with weren’t like that,” he qualifies.

“Personally, I made sure to say Shema Yisrael before going on stage, no matter where I was in the world. That way, I knew who gives me what, where the situation comes from, and who the applause is really for.”

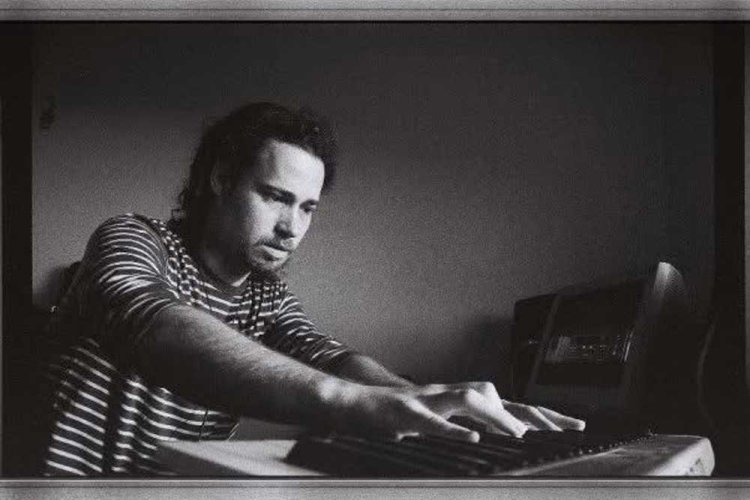

ניר בשנתו הראשונה באמסטרדם. קרדיט: אלירן קנולר

ניר בשנתו הראשונה באמסטרדם. קרדיט: אלירן קנולר

Today, much of your activity is related to antisemitism abroad. When did you first encounter it?

“From the very beginning. Two hours after landing in the Netherlands, I already encountered it. I was sitting at a café in central Amsterdam and tried to strike up a conversation with the table next to me. It turned out they were Turks with Dutch passports.”

When they realized he was Israeli, they hurled statements like: “You think you’re something special” and “you control the world,” along with other harsh words.

“I stayed silent. What I mainly remember is that everyone in the place was paying attention — watching them ‘go after me,’ and everyone stayed silent. It’s clear to me that if I had been Black or Arab, they would have intervened.

“In another incident that’s deeply etched in me, a 17-year-old said to his friend: ‘Jews are a filthy people, don’t speak the language of those garbage people.’ I stayed silent then too, and to this day it’s hard for me that I stayed silent. I still remember his face, even though it happened in 2007.”

עודד ניר כילד, 1979. קרדיט: בן לם

עודד ניר כילד, 1979. קרדיט: בן לםBut despite everything, you lived there many years. Didn’t these events make you consider leaving?

“My national consciousness back then wasn’t strong enough to overcome my personal ego and my desire for self-fulfillment. And in general, people tell themselves stories in order to keep living and enjoying the benefits.

“Today I can say that the situations where I didn’t respond are the ones I remember most vividly. A person doesn’t forget humiliation, and there’s a level of humiliation that’s hard to live with. There’s a well-known saying: ‘When the Jew knew how to die, he knew how to live.’”

The massacre on Simchat Torah and the wave of antisemitism that followed didn’t spare Nir’s Dutch surroundings. Over the past two years, he has unfriended hundreds of people on social media after harsh statements they made about events in Israel and Gaza. As he quotes some of them, his typically calm tone changes instantly — it’s clear how deeply the issue affects him.

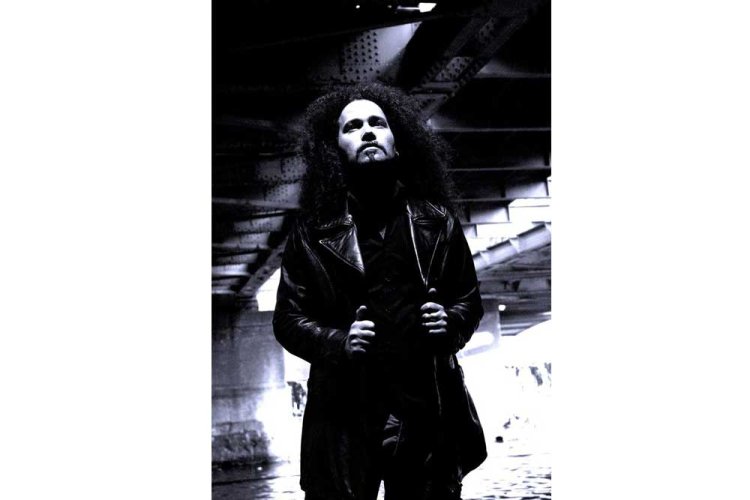

באמסטרדם, לפני כשני עשורים (קרדיט Victor Duran)

באמסטרדם, לפני כשני עשורים (קרדיט Victor Duran)Choosing Israel

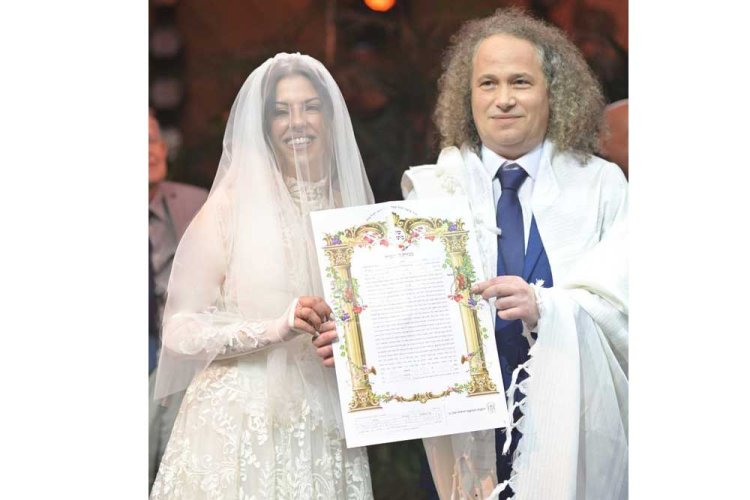

The decision to return to Israel began to take shape when a friend introduced him to his future wife, a resident of Rishon LeZion.

“On our first phone call, she asked me: ‘Oded, why do you want an Israeli woman?’ I answered: ‘I’m Jewish, and a Jew needs to marry a Jewish woman.’ That’s when she realized I would probably be her husband. That understanding deepened when I said: ‘Let it be clear — I’m Jewish, not a “Jew-ish.”’ It really moved her.

“Blessed be the Creator. Whoever shouts with intention is heard,” he says emotionally when speaking about his marriage. “But you have to be genuine and truly mean it.”

על הבמה באמסטרדם

על הבמה באמסטרדם“Livelihood Comes from God”

The couple’s original plan was to move back and forth between Rishon LeZion and Amsterdam. The riots in Amsterdam shook Nir and led him to decide to settle permanently in Israel.

What was the straw that broke the camel’s back during the Amsterdam incident?

“When I saw Dutch railway security personnel telling the Arabs that they were with them. This was even before the match. They spoke in Dutch — but I speak fluent Dutch.”

He describes the event as a horrifying experience. “It sharpens who you are and where you are. Those who didn’t understand then will understand again later. I fear the next time could be much worse than what Maccabi fans experienced. In the end, no real price was paid on the other side.”

About four months ago, Nir made aliyah. Today, he invests most of his time and energy in media activity.

ניר בחתונתו. קרדיט: אסף תמאם

ניר בחתונתו. קרדיט: אסף תמאםWhat message drives you in these interviews?

“I want to prevent relocation, encourage aliyah, and fight antisemitism in every possible way. I want to bring my brothers in Israel and in the Diaspora the truth about the situation we’re in.”

He is pained by what he calls the “inaccurate” media coverage of emigration numbers. “There are all kinds of ‘games’ here that I can’t understand. Why does the media push the relocation-from-Israel narrative so strongly? Why do major channels advertise queues for Portuguese passports, as if there’s a trend of leaving the country? Renewing a passport doesn’t make someone an emigrant. Some people want easier border control in Burgas with a Portuguese passport. That’s allowed. It doesn’t mean they’re leaving Israel.”

He adds that even army veterans who go on the “big trip” are counted as emigrants if they don’t return within a year — despite the fact that the vast majority do return. Another painful point for him is the large number of immigrants to Israel, which receives little meaningful attention.

ניר בחתונתו. קרדיט: אסף תמאם

ניר בחתונתו. קרדיט: אסף תמאםYou described how your national identity strengthened due to antisemitism. Did your Jewish and faith-based identity also change?

“Yes, absolutely. Thank God, my wife also brought me back into family life — holidays, kiddush, all of it. My faith in the Creator of the world, and the sense of protection and guarding I feel from Him, hasn’t changed, because I felt it all along.

“For twenty years I built my own house,” he concludes, “and now I’m going to fix things a bit, because I wasn’t a good Israeli. There’s a big sacrifice here in my career, and I lose money every month — but livelihood comes from God, and I’m not worried. That’s the truth. And the phrase ‘one who believes is not afraid’ is a true statement.”