Magazine

Life as a Jew in the World’s Most Dangerous City: Inside the Jewish Community of Caracas

Despite crime, political turmoil, and economic collapse, Venezuela’s Chief Rabbi reveals how Jewish life, faith, and community resilience continue to thrive in Caracas

- Chaim Gefen

- |Updated

Rabbi Yitzhak Cohen, Chief Sephardic Rabbi of Venezuela, inside the Caracas synagogue

Rabbi Yitzhak Cohen, Chief Sephardic Rabbi of Venezuela, inside the Caracas synagogueCaracas, the capital of Venezuela, ranks first on the list of the most dangerous cities in the world — according to a study by Forbes magazine, based on statistical data from international organizations. To illustrate, out of every 100,000 residents, about 130 are murdered each year. Powerful and extremely violent criminal organizations control the streets of Caracas, which is why it bears the dubious title of the most dangerous city in the world.

“Despite everything, and despite Venezuela’s global branding as a dangerous country, life here is beautiful,” says Rabbi Yitzhak Cohen, Venezuela’s Sephardi Chief Rabbi. “Most of the Jewish community is concentrated in Caracas, and I can personally testify that I have never been attacked in any way, even though I walk around the streets with clear Jewish symbols.”

Presidential Recognition

Rabbi Cohen, 70, born in Spanish Morocco, began serving as Venezuela’s Sephardi Chief Rabbi 48 years ago, after receiving rabbinic ordination in Israel. “At first I came to Venezuela on a two-year mission,” he recalls. “The Jewish community in Caracas needed Torah support, and my intention was to strengthen its spiritual standing and then return to Israel.”

After two years of spiritual and Torah activity, community leaders asked to appoint him as the country’s Chief Rabbi. “I had one condition: that the Rishon LeZion, Rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu (of blessed memory), agree to it. I didn’t want the appointment to be only internal to the community — I wanted it to receive the approval of Israel’s Chief Rabbinate, which indeed happened.”

Beyond recognition from Israel’s Chief Rabbinate, Rabbi Cohen’s appointment also received recognition from the Venezuelan government. “That wasn’t the goal,” he clarifies, “but the role I took upon myself required me to build a relationship with the government — if only in order to receive assistance and support on matters that required its approval.”

Like what, for example?

“Anything related to imports. For example, in Venezuela we don’t produce matzah or wine, and we need government approval to import these products from nearby countries where they’re produced under supervision and kosher oversight. If the government doesn’t approve it, we won’t have matzah and wine for Passover. The relationship I built with the authorities was not political,” he emphasizes. “The goal was only to help manage Jewish religious life and protect the Jewish community.”

A President Hostile to Israel

In the late 1990s, Hugo Chávez, leader of Venezuela’s socialist party (PSUV), rose to power. Until his presidency, Venezuela maintained diplomatic relations with Israel, but those ties deteriorated following his antisemitic remarks. In 2009, during Operation Cast Lead, Chávez accused the IDF of “genocide” and carrying out a “Holocaust,” and expelled the Israeli embassy staff from the country.

Did you feel antisemitism from Chávez?

“No. I met him three times in the presidential palace. We spoke about religious matters on the agenda, and he never showed antisemitism toward me or toward the community. We had good relationships based on respect and appreciation, and more than once he said he was my friend. Everything I asked and demanded from him for the needs of the Jewish community — he helped and supported.”

How does that fit with the hostility he expressed toward the State of Israel?

“One must understand one thing: leaders like Chávez exist in many countries, and they separate between Jews and the State of Israel. In Iran, for example, Jews live there, even though the Iranian regime tries to destroy Israel. Our worldview is that the State of Israel is inseparable from the Jewish people — and of course that is the correct view, but in their eyes ‘the Jewish people’ and ‘the State of Israel’ are two completely different things.

“In a broader perspective,” Rabbi Cohen adds, “there are two types of antisemitism. There’s the new antisemitism characterized by hatred of the State of Israel and opposition to its existence, and there’s cultural antisemitism that passes from generation to generation. In Venezuela there isn’t cultural antisemitism, for one simple reason: the Venezuelan people barely know what Jews are. So even if there are expressions of hatred or incitement, it isn’t directed at the Jewish people.”

Still, during Chávez’s rule, the “Tiferet Israel” synagogue in Caracas was attacked. This happened only days after Chávez expelled Israel’s ambassador, making it hard not to see a connection.

The attack took place on Friday night, January 31, 2009. An armed gang broke into the synagogue and took control of the building for several hours, during which they vandalized property and caused extensive damage. Members of the gang — including former police officers, sprayed antisemitic and anti-Israel graffiti and called for the expulsion of Jews from the country. They were later sentenced to ten years in prison.

“The attack happened at the large, historic synagogue located in central Caracas, but by then most of the community had already moved to the eastern part of the city, where we built a new and magnificent synagogue,” Rabbi Cohen says. “A few Jews remained in the city center, but the attack took place late at night, so they were at home and didn’t know what was happening nearby. By the grace of Heaven, there were no physical injuries.”

הרב כהן עם הנשיא לשעבר הוגו צ'אבס, בארמון הנשיאות

הרב כהן עם הנשיא לשעבר הוגו צ'אבס, בארמון הנשיאותWhy did you move to the eastern part of the city — did you suffer harassment in the center?

“This happens everywhere in the world: Jews are always moving around. Consider New York, for example — many Jewish communities live there and move from place to place. In Venezuela as well, the Jewish population moved to the east of the city. We did not suffer harassment in the previous place we lived, and there is no other Jew here who is persecuted because of Judaism. We walk around the streets with Jewish and religious symbols, and no one harms us.”

בית הכנסת הספרדי במזרח קראקס

בית הכנסת הספרדי במזרח קראקסStrange Politics

Surprisingly — or perhaps not, President Chávez did not condemn the synagogue attack. Nicolás Maduro, who was then Venezuela’s foreign minister, was the only one who publicly condemned the antisemitic attack. After Chávez died in 2013, Maduro succeeded him. Maduro’s policy toward Jews and Israel was the opposite of his predecessor’s: he expressed friendship toward the Jewish people and even announced his intention to renew diplomatic relations between Venezuela and Israel. “Maduro has another advantage over Chávez,” Rabbi Cohen says. “He claims that his family was originally a Sephardi Jewish family.”

In 2018 Venezuela held presidential elections. Maduro won, but was later accused of stealing and falsifying the election. His rule increasingly took on the character of dictatorship and communism, and the U.S. Department of Justice accused him of turning Venezuela into “a criminal organization serving drug traffickers and terrorist groups.” The U.S. government placed a $15 million bounty on his head.

Against the backdrop of a constitutional crisis, opposition leader Juan Guaidó declared himself interim president, a move supported by Venezuela’s National Assembly. Many countries — including the U.S. and Israel, recognized him as president, ignoring Maduro’s presidency. In early 2023, Guaidó was removed by the opposition itself, which decided to dissolve the interim government he led.

בית הכנסת בקראקס

בית הכנסת בקראקסWhich of the two is more identified with the Jewish community and supports it?

“Maduro is the one in control, and the rest are a small minority that is nullified by the majority,” Rabbi Cohen says. “That small minority has no power and no leadership — especially since he is currently in the United States. The Torah teaches us, ‘and to the judge who will be in those days.’ Today, the ‘judge’ is Maduro, and we need to support him and merit protection for the Jewish community — without entering political matters that won’t help us at all, to put it mildly.”

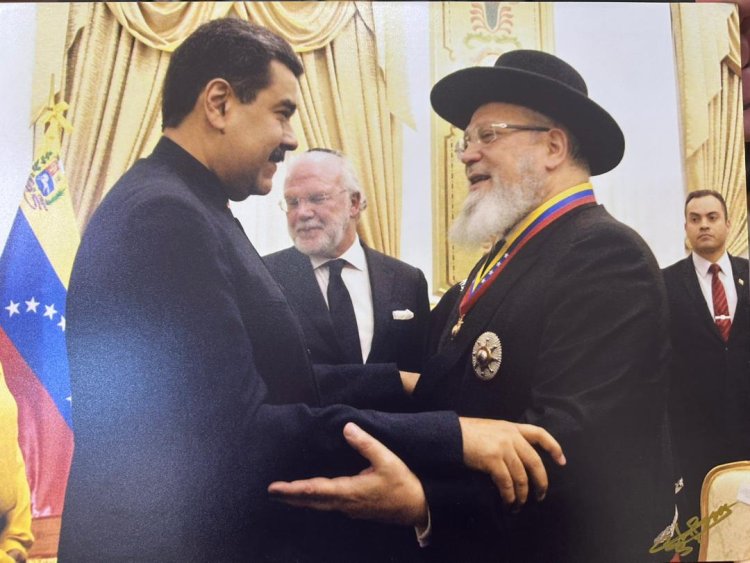

עם הנשיא ניקולאס מדורו

עם הנשיא ניקולאס מדורוHunger and Thirst

Venezuela’s economy has experienced ups and downs. The decline reached its peak under Chávez. During that period, many Jews fled Venezuela, claiming they left because of growing state antisemitism under Chávez. “They didn’t flee because of antisemitism,” Rabbi Cohen insists, “but because of the unstable economy.”

How did the Jewish community cope with the economic crisis?

“The community supported Jews — financially and socially, who could not afford their monthly expenses. It was a difficult period, but we went through it together. Every Jew received the help they needed. The community also funded medical treatments for those who required them.”

With so many serious challenges — security, economic, and social, don’t Venezuelan Jews dream of leaving and immigrating to Israel?

“Of course. It’s the dream of every one of us. But aliyah is a personal matter, and each Jew must decide for himself. If I want to rise spiritually, for example, that’s my personal matter and not anyone else’s. Exactly the same here: each person must decide for himself when he fulfills his dream and moves to the Land of Israel.”