Magazine

From the Operating Room to a Life-Saving Gift

After witnessing the suffering of dialysis patients and the power of unity in times of war, Dr. Eli Bechor made a profound decision

- Hidabroot

- |Updated

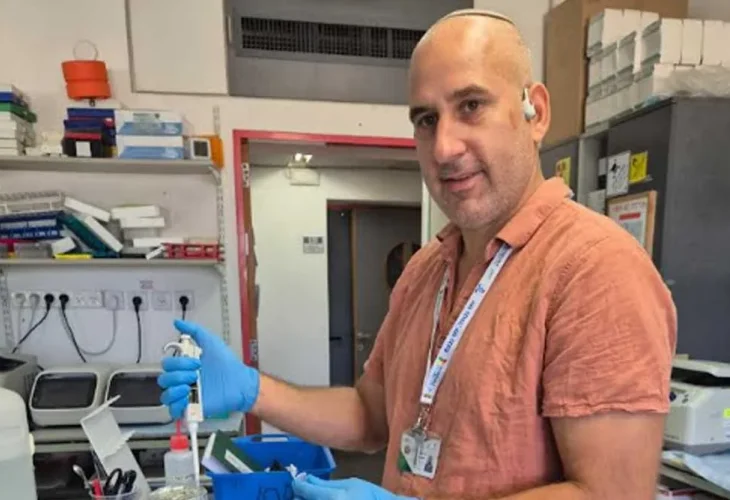

Dr. Eli Bachor

Dr. Eli BachorAbout seven years ago, a message arrived on the cellphone of Dr. Eli Bechor, a senior surgeon at Hasharon Hospital in Petah Tikva. The message came from a fellow soldier from the Golani Reconnaissance Unit. He informed his reserve-unit friends that he was flying to Switzerland to undergo assisted suicide.

“I’m just saying goodbye and want to tell you farewell. You were an important part of my life,” he wrote.

“This was a lone soldier with no family. At the age of 35, he was suddenly diagnosed with kidney failure,” Dr. Bechor tells Hidabroot in an interview. “He was forced to undergo dialysis treatments and decided that this life was not for him.”

Of course, his friends could not remain indifferent. “We began spreading his story everywhere we could — the story of a soldier who came to Israel on his own, served in an elite unit, and suddenly found himself suffering from kidney disease out of nowhere.”

Their efforts bore fruit. Through the organization Matnat Chaim (Gift of Life), a person who was exposed to the story came forward and volunteered to donate a kidney.

“The transformation our friend went through was unbelievable,” Bechor says. “Not only did the transplant bring him back to where he was — it propelled him ten steps forward. From being a lonely person with very limited income, he built a family and developed a high-tech startup that now operates worldwide.”

“Like Taking a Person Out of the Grave”

The world of kidney transplants is not foreign to Dr. Bechor, 41, married and a father of five. He lives in the religious moshav Kfar HaRoeh in the Hefer Valley and specializes in surgery and trauma. In his ten years as a surgeon, he has taken part as a senior team member in around thirty transplants.

“As a surgeon, I’ve encountered kidney patients before and after transplantation, and I’ve even operated on some of them myself. Another case close to home was when I operated on my neighbor — a healthy woman whose kidney function suddenly deteriorated. She developed kidney failure and required dialysis.”

That personal connection deeply affected him. He witnessed her suffering during dialysis treatments and then saw the new life she received after the transplant. That case, together with the story of his army friend, became one of the main motivations that eventually led him to donate a kidney himself.

What touched you most about the suffering of dialysis patients?

“The lives of people with kidney failure are not really lives,” Bechor explains. “First of all, you’re not productive — you can’t work or progress in life. Beyond that, your entire existence revolves around dialysis. Treatments are every other day — one day treatment, one day rest. On the treatment day you spend the entire day hooked up to a machine; the next day you’re completely exhausted and need to recover; and the day after that, another treatment.”

During dialysis, patients are connected to a machine that replaces kidney function. For several hours, all the blood in their body circulates through the machine. In addition, they face many restrictions, including severe limits on fluid intake.

“But the restrictions are actually the smaller part,” Bechor emphasizes. “The main issue is that you don’t have a life. There is no day off when you can truly function, study, work, or be with your family. Quality of life for dialysis patients is extremely poor, and they suffer from many chronic illnesses. Their life expectancy is very short — less than ten years. At age 80, that’s one thing. At age 36, it’s unbearable.

“As a surgeon, I’ve seen that when you take such a person and donate a kidney, you are literally pulling them out of the grave and turning them into a healthy person. I’ve been involved in dozens of such procedures. The process — both for the donor and the recipient, is complex and challenging, but ultimately not long, and the risks are relatively low. The transplant teams across the country are very experienced.”

When did you decide to donate a kidney yourself?

“After the story with my army friend,” he says. “I realized that there was something here, and that I myself had to donate — only the question was when. I believed it was the right and good thing to do.

“As a doctor, I understand that the risks — both of the surgery and of living afterward with one kidney, are minimal to almost negligible. On the other hand, what you give the recipient is enormous. For me, it was simple math. It was clear to me that one day I would donate.”

“One Body”

In 2023, Dr. Bechor was in Canada for a fellowship, a specialization lasting one to two years. He lived there temporarily with his family.

“On October 7, when the war broke out, I got on the first plane back to Israel,” he recalls. “I wasn’t the only one. The vast majority of doctors in Canada under similar circumstances — Israelis there for a year or two, dropped everything and returned immediately.

“All the flights were completely full of people who left jobs, studies, or post-army trips. They took the first plane home because it’s your people, and you don’t stay abroad when your people are at war.”

The flight deeply shook him. “I saw young people with long hair lying under seats because there was no room, people sharing food with one another. I always say we didn’t even need fuel to fly that plane — the energy of the people onboard was enough.

“During that flight I understood: okay, I’m coming to Israel, I’ll do reserve duty and whatever I can. But this people is so much one body, that it isn’t fair for me to keep two kidneys when someone else doesn’t even have one.”

Bechor served for about a month as an IDF physician, then returned to his family in Canada, completed his fellowship, and came back to Israel that summer.

“When I returned, I began the process with Matnat Chaim. We found a man my age, who was healthy, working, functioning, with a family and children. Suddenly, a disease of unknown origin struck his kidneys. He didn’t smoke and hadn’t done anything that could damage them. The illness simply appeared out of nowhere.

“Because of kidney failure and dialysis, he suffered a cardiac event and required bypass surgery at age 42 — something extremely rare. Of course, he also had to stop working. From a normal, functioning man in his forties, he became disabled and broken at 43.”

Beyond these details, Bechor prefers to protect the recipient’s privacy. He adds only that they met for the first time on the day of the transplant and have remained in close contact.

When you realized the donation was really going to happen, did fears arise?

“Not about the procedure at all,” he says. “I’ve been present at around 2,500 surgeries in my life — the operating room is like my second home, if not my first,” he laughs. “I have no fear of surgery, certainly not of kidney donation, which is very safe.

“I also wasn’t worried about the day after. We have enough medical data to know with a high degree of certainty that there is no significant impact on life. Today I live a completely normal life. I’m two months post-donation — last night I played soccer until midnight, and today I operated all day. I have no limitations.”

How did family members and colleagues react?

“Clearly, anyone who donates a kidney does something that deeply moves the people around them. I’ve always viewed kidney donors as extraordinary individuals. But there was something especially powerful about the fact that a person from the medical world — a surgeon who performs transplants himself was doing it.

“I received hundreds of emails, messages, and calls from people who had received kidney transplants and from people whose family members need one. People who were debating whether to donate told me plainly: ‘Now that I see a surgeon donating a kidney, I feel safe to do it myself. I know it’s truly okay.’

“Every donation has two layers of impact: first, it’s a noble and valued act in itself; second, it influences wider circles beyond the donor and recipient. Maybe someone will read this article and say, ‘It seems safe enough and legitimate enough — maybe I’ll think about it too.’”

Is that why you agreed to be interviewed?

“Exactly. There are circles of goodness here — like throwing a stone into water and watching the ripples spread. We’re trying to pass the good on.

“I’m in a WhatsApp group of donors. One of the members planned to give a lecture and asked everyone to write why they donated a kidney. Dozens of responses came in — many of them very moving. I think the common thread is the feeling that you are part of something larger than yourself. We are all a divine spark from above, but there is also one great soul of the Jewish people, and each of us is a small organ within that soul.”

What did you write?

“I wrote that I donated a kidney because it didn’t seem fair that I have two kidneys while he doesn’t even have one. It’s like walking in the desert with two bottles of water while someone next to you is dying of thirst — it makes no sense.

“I donated and returned to a normal life. The donation isn’t constantly on my mind. But for the recipient — he will never forget the deep pit he was in, and how he returned to normal life. It’s simply not fair to walk around with two kidneys in such a situation.”