Facts in Judaism

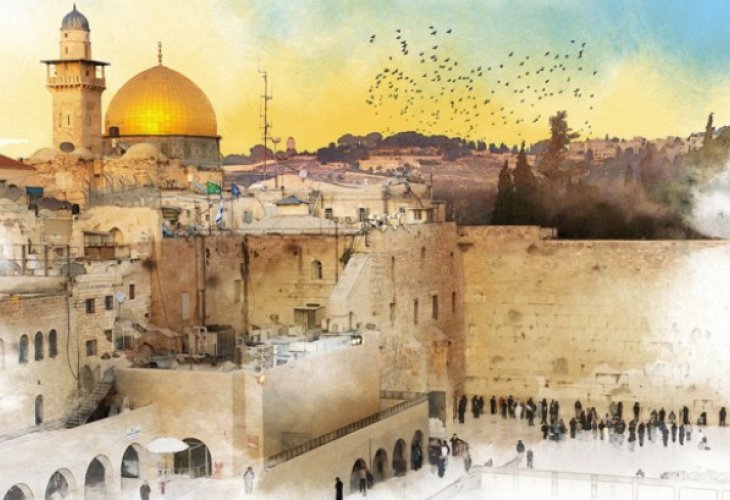

Jerusalem: A City Between Heaven and Earth

From ancient holiness to eternal longing

(Photo: shutterstock)

(Photo: shutterstock)Jerusalem is not just a place—it is a promise, a prayer, a longing that spans generations. From the earliest verses of the Torah to the quiet whispers of prayer said in every corner of the world, Jerusalem stands as the spiritual heart of the Jewish people. Its past is steeped in sanctity, its present wrapped in yearning, and its future the subject of prophecy and hope.

Jerusalem is first mentioned in the days of Abraham, when the Torah refers to Melchizedek, king of Salem—understood by the Midrash to be Shem, the son of Noah and king of Jerusalem. Later, Abraham himself names the site of the binding of Isaac “Hashem Yireh”—“Hashem will see.” The Midrash weaves the two names together: Shem called it Salem (peace), Abraham called it Yireh (vision), and Hashem said, “Let it be called Jerusalem (Yerushalayim),” uniting sight and peace, Divine revelation and harmony.

In the Tanach, the city’s name appears mostly as Yerushalem, a rare hybrid of those two roots, with only five places recording it as Yerushalayim. Yet in the Oral Torah—the Mishnah, Tosefta, Talmud, and Midrashim—the name Yerushalayim becomes the enduring term, reflecting the layered and sacred identity the city has held for millennia.

Jerusalem's geographic location is not incidental. When the tribes entered the Land of Israel under Joshua, Jerusalem stood on the border of Judah and Benjamin, a symbolic placement between territories, uniting the people from its very foundation. Here, the Holy Temple would be built—the site chosen by Hashem, as written in Deuteronomy: “Only to the place that Hashem your God will choose… to place His name there.”

Indeed, after the construction of the First Temple, the verse proclaims, “In Jerusalem, the city I have chosen for Myself to place My name there.” According to the Midrash, before Jerusalem was chosen, the Divine Presence could dwell anywhere in the Land. But once Jerusalem was selected, it became the singular home for the Shechinah (Divine Presence). Hashem assessed every city and found only Jerusalem worthy of the Temple—a choice both absolute and eternal.

Jerusalem is also the gateway of prayer. When Jacob dreams of the ladder reaching to heaven, he awakens and says, “This is none other than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven.” The Sages understood this to mean that prayers offered in Jerusalem ascend directly to the Throne of Glory. This is reflected in Jewish law: a person outside the Land of Israel faces toward Israel when praying; someone in Israel faces Jerusalem; in Jerusalem, one turns toward the Temple; in the Temple, toward the Holy of Holies. All spiritual direction leads to this holy city.

The sanctity of Jerusalem is also codified in halacha, where it ranks among the ten levels of holiness in the Land of Israel—greater than walled cities but beneath the holiness of the Temple Mount. Its spiritual gravity is so central that even after the destruction of the Temple, the Sages wove the memory and hope for Jerusalem into nearly every Jewish prayer and blessing.

In Birkat HaMazon (Grace After Meals), the third blessing is devoted entirely to the rebuilding of Jerusalem. King David instituted the plea for “Israel, Your people and Jerusalem, Your city,” and King Solomon added mention of the Temple. The blessing ends with a heartfelt request: “Rebuild Jerusalem, the holy city, speedily in our days. Blessed are You, Hashem, Who in His mercy builds Jerusalem.”

Similarly, the daily Amidah includes a specific blessing for the rebuilding of Jerusalem. The second blessing after the Haftarah on Shabbat also references Jerusalem: “Have mercy on Zion, for it is the source of our life.” Even in the evening prayer on Shabbat and holidays, we conclude: “Who spreads the shelter of peace… over all His people Israel and over Jerusalem.”

This longing was echoed on Yom Kippur by the Kohen Gadol (High Priest) and by the king at the Hakhel assembly, who mentioned Jerusalem and Zion in their respective blessings: “Who chooses Jerusalem” and “Who dwells in Zion.” Even in moments of great joy—weddings included—Jerusalem is remembered. One of the Sheva Berachot (the seven wedding blessings) asks, “May the barren one rejoice and be glad… who makes Zion rejoice with her children.” This is no coincidence. The Talmud teaches that we must elevate the memory of Jerusalem at the height of our joy: “If I do not remember you, O Jerusalem, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth… if I do not place Jerusalem above my highest joy.”

In fact, Jerusalem is likened to a bride. The future joy of its rebuilding is compared to a wedding, as the verse says: “As a bridegroom rejoices over his bride, so will your God rejoice over you.” For this reason, some customs conclude wedding blessings with phrases such as: “Blessed are You, Hashem, who gladdens His people and builds Jerusalem.”

Today, Jerusalem is once again a vibrant city that pulses with Jewish life, yet we still await its full spiritual redemption. Though rebuilt with stone and filled with people, the yearning for the return of the Divine Presence, the Temple, and the complete fulfillment of prophecy remains.

Jerusalem is both history and destiny. It is the city chosen by Hashem, the city toward which all prayers are directed, the city remembered in joy and sorrow, and the city we long to see restored in its full glory.