The Transformation of Silverdon: From Jamaican Reggae to Talmud Study

The teens of the '90s might recognize him by his stage name "Silverdon," but today Gili Benjamin is in a completely different place. No longer pursuing a doctorate, embracing his Yemenite roots, he is grateful to his grandfather for keeping him from entering churches and is now most excited by studying the Talmud in a kollel. A surprising interview.

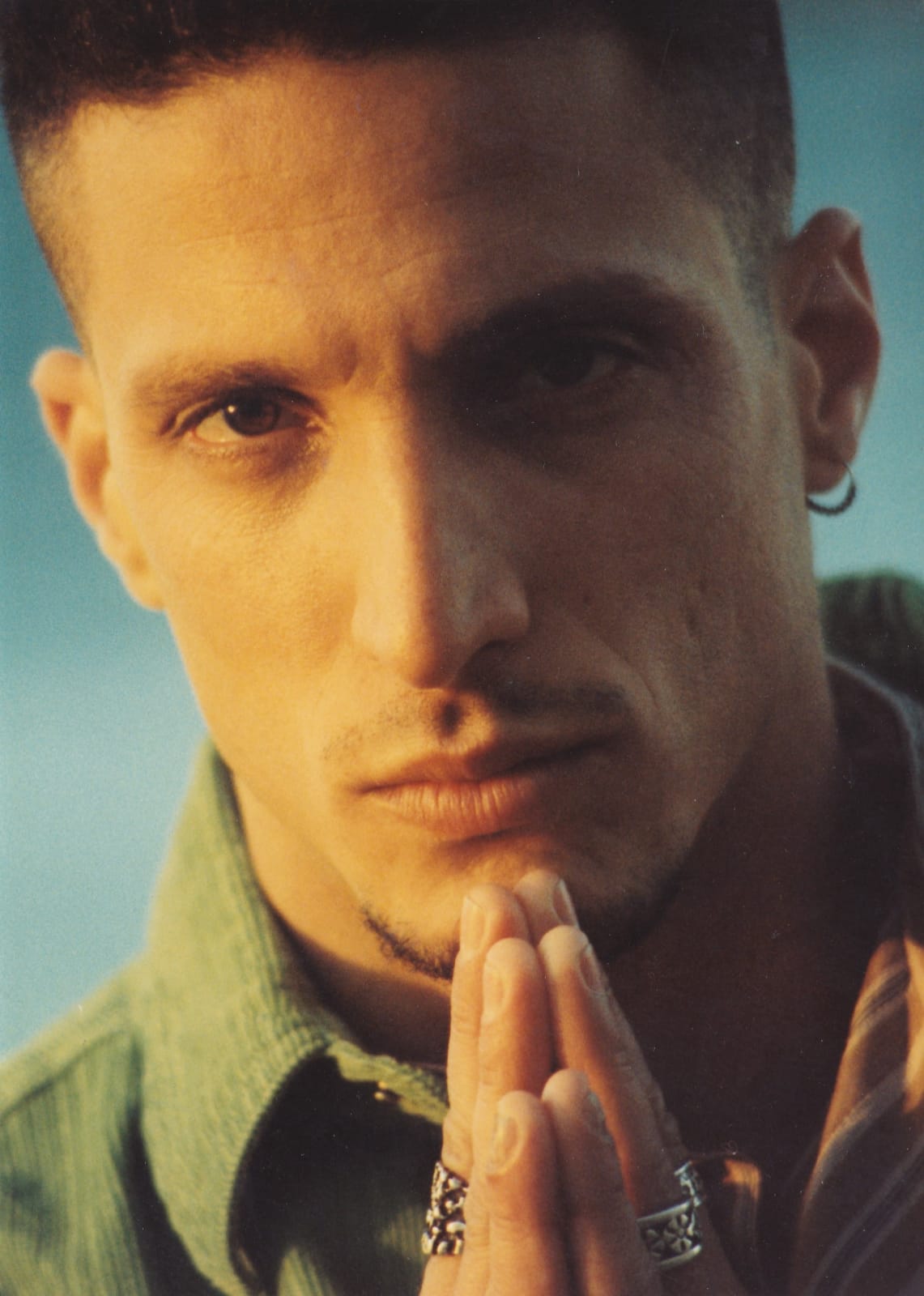

Gili Benjamin (Photo: Tal Akuka)

Gili Benjamin (Photo: Tal Akuka)As a 15-year-old teenager, Gili Benjamin fell in love with reggae music and spent many hours around recordings, listening, and getting to know the industry. In the '90s, young Gili traveled to the U.S. after his military service in Israel for a sort of "preparatory work" in Miami and New York, and from there he moved to Jamaica. He quickly climbed to the top of the Jamaican music scene, earned the nickname "Silverdon," released a debut album that became a blockbuster hit, and performed with artists like Rita and Ziggy Marley. Only many years later, Gili returned to his roots and strengthened.

Gili was born to a Yemenite father and a Polish mother, builders of Tel Aviv. He grew up in the port city of Ashdod in a neighborhood of Ashkenazi communities, and it took him time to rediscover his roots.

"The Ashkenazim didn't think I was Ashkenazi enough, and on the other hand, in the Yemenite Vineyard I was considered 'the blond one.'" he recalls in an interview on Hidabroot about his childhood in the neighborhood in Ashdod. "I remember that due to the neighborhood atmosphere, I was really educated to be ashamed when my father spoke with a Yemenite accent with the Ayin and the Het sounds. I felt socially detached, but that was a different era. Many sacred cows have been slaughtered since then. Once I was already a teenager, I reached other insights. Today I have friends from all ethnicities and all kinds, I listen to Sephardic and Ashkenazi rabbis, and I think people should be themselves - and not be ashamed."

"I Lived in a Movie, Didn't Let Extras Interfere"

In Jamaica too, he was quite detached. Gili was the only white person in a black neighborhood, and later became the first white person in the black music arena. "I lived in a movie, where I was the main star, and I didn't let this or that extra interfere with the script. I made a supreme effort to integrate into the Jamaican culture. Everyone already knew me because I was funny, but in Jamaica, they look at you differently not only if you're white but anyone who looks different or foreign."

Recently, with his return to the music world, Gili was interviewed for a radio show in Florida with broadcaster Gregory Cole. On the broadcast, he talked about that time: "I hadn't looked in the mirror for a very long time, I functioned as if I was black in every aspect, and it was clear to me that it was a movie. Today it's the opposite, I have a single called 'White Man Can't Turn Black' - a funny song about someone trying to be black."

When Gili returned to Israel in the 2000s, he tried to replicate his success in Hebrew. He recorded an album called "Speak!" and hosted artists like Fishy HaGadol and Nimrod Reshef from Shabak S, familiar names in the Israeli black music scene. Apparently, Israel wasn't quite ready for him, and the album didn't succeed. Gili began working with his father in the Port of Ashdod.

Years later, when his father passed away, Gili underwent a process that changed his life. "I started getting closer to tradition. My father, of blessed memory, grew up with sidelocks in the Yemenite Vineyard, but over the years he became a big star on the 'Shimshon Tel-Aviv' soccer team and after he retired, worked as a sea captain. He lived a modern life, but on holidays and Shabbat, he went to the synagogue and knew how to chant perfectly. There was silence in the synagogue when my father read. When he passed away, I started going to lessons in the kollel and wanted to do something that would please him. As I began to strengthen, I prayed every day and used the language of the Sages on a daily basis. I thought it would be nice to know the history of the Jewish people and the Hebrew language, which I had already begun to memorize."

Gili completed a bachelor's degree in the Hebrew language and the history of the Jewish people with distinction, with a recommendation for a doctorate. "During my studies, I discovered a disdain for the status of a doctorate. I no longer held it in such high esteem. There were truly those who invested time and energy, and there were also those who copied. I understood that my father's soul's merit would no longer come from the degree, but through those texts that I read in a spiritual manner. Even reading without understanding them could be beneficial."

Gili is currently divorced and has three children (12, 10, 5) in joint custody, to whom he tries to instill values of Judaism and morality. "They are with me half the week, and when they are with me, I do everything - pick them up from school and activities, take them surfing, and in the evening they know it's Torah time. On Shabbat, they even come with me to morning prayers. Each time I throw them a different incentive. I try to instill in them values, to show them the way.

"I give them the foundation, values of interpersonal kindness, giving charity, respecting sages. They are overall believing kids. They read in Yemenite fluently, and that's already a blessing, and at other times, they just do what all kids do - play soccer and go surfing with me in the sea, etc."

It seems that regarding Judaism, you are more connected to the Yemenite tradition.

"I study in a kollel 3 times a week and learn there with people from all backgrounds – Yemenites, Moroccans, Ashkenazim, and Iraqis. In our history, there are prominent Ashkenazi rabbis and not a few Sephardic rabbis. The Torah is one and unique. But if we talk about customs, then according to the Sephardic sages like Abraham Ibn Ezra, Rabbi Yehuda Ibn Tibbon, the Radak, they are all linguists from the 11th and 12th centuries who wrote entire books on grammar and how to pronounce it. Both according to what they wrote and the sages of the Tiberian school, the Yemenite pronunciation is the original."

Won't Say Jah

About two years ago, Gili returned to the reggae music world. One thing led to another, and in the past year, the subject gained momentum. Recently he even released a new single called "World Clash" about Jewish history.

The song drew many responses, some of which weren’t favorable, especially from his friends in Jamaica. "I sang about Jewish history, about the First and Second Temples. 99% of the responses were overwhelmingly positive, but there was 1% of people who got upset and wrote to me ‘Why don’t you tell them the truth?’ I rubbed my hands delightedly and started writing detailed responses with verses from Psalms, directing them to the scripture. Overall, we had a critical but respectful dialogue among people with different opinions. There was no hatred, just an exchange of sources."

Why did the song cause controversy? They believe in Hashem too.

"Yes, but not in the tenets of Jewish faith. In fact, they claim they are the original Israelites. The Rastafarian religion is a mix of Judaism and Christianity, and they have their own world. One must understand and be cautious of this. Today the youth loves to adopt the red-yellow-green colors - the colors of Jamaican culture - but getting into spirituality is something that clearly no longer aligns with the Shulchan Aruch."

In the past, you said reggae is idolatry.

"I said the Rastafarian religion is idolatry. I sing reggae but will never say 'Jah' or 'Rastafari,' like other reggae singers do. I love and respect all human beings for who they are, but theologically, it is separate from Judaism."

"I've Never Entered a Church"

His return to the stage was expected but not predictable. About three years ago, he received an offer from a pair of DJs who wanted to host him at one of their performances. "I was afraid I wouldn't be able to sing. All these years I was busy with Yemenite melodies, Torah reading, and reciting Psalms, which filled me with joy. I told them I hadn't performed in years, but they asked me to come. I prepared two songs and prayed I would be able to finish them. When I got on stage, it all came back, as if there hadn’t been a break. I began to understand that it’s still in me, and from there, one thing led to another. In the past year, I've performed, appeared on radio shows, sold tickets to shows, and people came. Who would have believed people remember? It was amazing. I combined old and new material, and I'm mainly happy with the feedback I received. It encourages me to keep creating. It's clear that today children and family come above all else, but it's also fun to create and perform, especially when it comes from a spiritual place."

(Photo: Tal Akuka)

(Photo: Tal Akuka)Why even return to the stage? Haven't you had enough?

"I thought I had done it all, had enough, fulfilled all my dreams, and I draw my spirituality from studying Talmud. I just finished a tough topic, and it filled me. But it still doesn't contradict my love for music."

What are you writing about these days?

"Historical texts, Jewish texts, and also light texts about life itself. That said - there is no inappropriate content in them. Recently I also started writing for industry friends."

Is there a plan for another tour in Jamaica?

"I am currently releasing a second song in Jamaica produced by someone very well-known, a 'childhood' friend from my time there. He knows me well and saw how I developed and climbed the ranks. You know you're in a good position when Jamaicans pay you for reggae, and that's what's happening now, there’s starting to be interest."

(Photo: Tal Akuka)

(Photo: Tal Akuka)What do you think is the best thing about Judaism?

"The Torah. Everything that Hashem does is good, and the Torah is a complete, spiritual ethos. I hope, with Hashem's help, to marry again, but right now I'm trying and it manifests in less gossip, fewer sins. I'm not Rabbi Akiva, but that's my ideal, and the look is always upwards, to progress. I thank Hashem for everything He has given me and for my journey in life."

Finally, which Jewish figure do you admire and draw inspiration from?

"A figure whose shoes are hard to fill, if not impossible - Grandpa Ibrahim of blessed memory, who was a sum of all the good traits in Judaism. I was fortunate to know him until I was 12, then he passed away. I didn't understand his language because it was heavy Yemenite, but his spirit was something you couldn't not feel. His image protected me in Jamaica. Many times I was invited to Sunday events at the church, but I never entered. His image was always before me. He had the innocence of the old generation. Everyone has a grandparent from that generation who embodies these virtues, but for me, he was a model for great values."