Jewish Law

Moving Through the Stages of Mourning

Our Sages have outlined a path leading from intense grief back to life

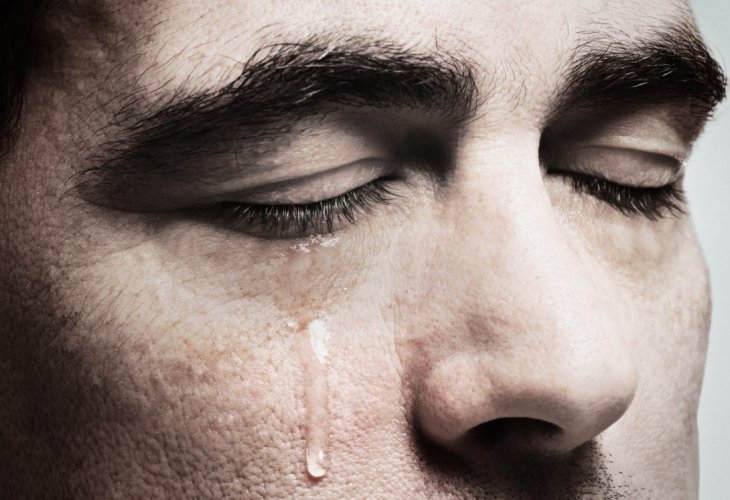

(Photo: shutterstock)

(Photo: shutterstock)Grieving within appropriate boundaries

While adhering to the laws of mourning is essential and expressing grief and sorrow important, we must keep in mind that excessive expressions of grief are not beneficial. Therefore, our Sages stressed that grief should be maintained within appropriate and reasonable boundaries, to ensure that excessive sorrow does not hinder the mourner’s return to normal life once the mourning period is over. One example of this is the law mentioned in Parshat Re’eh, the prohibition against cutting one’s body or pulling out one’s hair as an expression of grief over a loved one’s death.

Excessive weeping

While mourners are encouraged to weep, excessive weeping is discouraged. The Gemara cites a verse in Jeremiah that states: “Do not weep for the dead, nor bemoan him,” which the Gemara explains as an injunction against excessive weeping and inappropriate mourning. However, the Sages also cautioned against going to the opposite extreme — minimization of expression of mourning. A person who does not allow himself to cry when a loved one passes away may appear strong and resilient to those around him, but our Sages knew well that this would not be to his benefit. The Radbaz (a prominent rabbi of the Middle Ages) writes that if one’s child passes away and he does not shed a single tear, this highlights the person’s negative character traits, especially hardness of heart.

Our Sages established specific times when mourners may immerse themselves in their grief, such as when visiting the grave of the deceased at the end of the shiva, at the end of the thirty-day mourning period, at the conclusion of the first year after the passing, and on each anniversary. During visits to the gravesite, accumulated grief can be released while prayers are offered for the elevation of the deceased person’s soul.

Jewish law (halachah) also differentiates between various timeframes for mourning. Seven days are allocated for returning to a more or less normal routine, but a person needs far longer to free himself from a deep attachment to a deceased spouse and consider the idea of remarriage. According to halachah, one may not remarry until three festivals (Pesach, Shavuot, and Sukkot) have passed. The reason for prescribing such a lengthy waiting period is, the rabbis tell us, “In order that he will forget his love for his first wife, after experiencing the joy of three festivals.” The nature of joy is that it makes one forget sadness, and the power of several accumulated joys can help a mourner to move on from mourning over his deceased wife and be able to contemplate marrying another woman and building a healthy home.

Community involvement in the mourner's grief

When a person loses a loved one, relatives and friends are expected to do what they can to ease the mourner’s pain. This is expressed via the mitzvah of “nichum aveilim—comforting mourners.”

Consoling a mourner involves listening to them pour out their feelings and actively participating in bearing the burden of their grief. In fact, those who come to comfort are also expected to share in the grief to a degree, and this alleviates the mourners’ distress. Rashi (the great medieval rabbi and commentator on the Torah) explains that one of the reasons why we rip the clothing of the children of the deceased person is “so that the onlookers should weep at seeing even a child’s garment torn.”

Those who have seen even young children reciting Kaddish for a parent will certainly identify with the anguish this causes, and this is an anguish that the community is supposed to feel.

The family of the mourner

The closer a person is to a mourner, the more they are expected to identify with the feelings of loss. The Shulchan Aruch (Code of Jewish Law) stipulates various customs for relatives of the mourner which are no longer practiced in our day and age. However, the spouse of someone mourning a parent is obligated to adapt his or her behavior for a specified period of time.

Rehabilitation — a gradual process

Mourning in Jewish law is a process which begins with external expressions of intense grief and gradually eases those bereaved back into regular daily life. Immediately upon the passing of a close relative, mourners enter a state called “onen” in which they are expected to be immersed in their sorrow to the extent that they are actually forbidden to pray and fulfill the commandments. They even eat without making blessings.

The next stage of mourning is that of the day of the funeral. On this day, a mourner does not put on tefillin and all the halachot of the shiva period come into force.

The following stage comprises the first three days of mourning with their special laws. Then come the rest of the days of shiva, when mourners are still expected to be entirely focused on their loss.

After the shiva ends, mourners enter the stage of the “shloshim,” the first thirty days following the funeral. During this period several of the shiva restrictions no longer apply but mourners are still forbidden to cut their hair and nails, for example.

The year of mourning applies only to those whose parent has passed away. During these months, a bereaved child may not listen to music or participate in celebrations such as weddings. And, they will continue to mark the parent’s passing every year on the anniversary, in order to maintain a perpetual connection between parent and child.

Our Sages tell us that, “It has been decreed that the dead should be forgotten from the heart after twelve months.” Memories will always remain but grief and sorrow naturally fade with the passage of years.

***

Every Jew who is in mourning for a loved one is obligated to follow this path from grief to healing and should not imagine that he can develop his own methods of recovery from loss. Paths that differ from the way of Torah may appear beautiful and tempting, and may even promise euphoria, but the illusion will be fleeing and over time, the damage they inflict will make itself felt.

The warning to mourners against following an independent path that is not in the spirit of the Torah is summarized by the Rambam (Laws of Mourning 13:12) in a few words: “Anyone who does not mourn as the Sages commanded is cruel. Rather, one should fear and worry and examine their deeds and return in repentance.”