The Holocaust

Holocaust Survivor Moshe Blech: From Auschwitz to Liberation in Israel

A teenage boy’s journey through death marches, labor camps, and miracles of survival

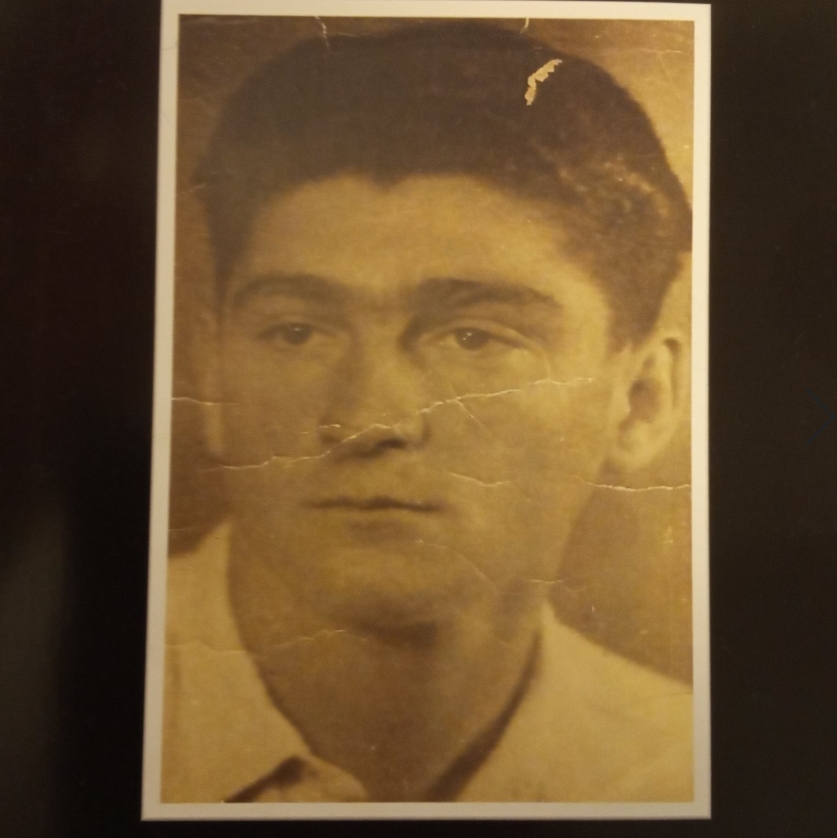

In the circle: Young Moshe Blach (Photo: Private Album)

In the circle: Young Moshe Blach (Photo: Private Album)The stories of Holocaust survivors are always difficult and chilling. Such is the story of Moshe Blech, who endured immense suffering during the war.

“I was born in Czechoslovakia, and I first felt the horrors of the Holocaust when I was 15,” Moshe begins. “At first, we were taken to Auschwitz, where my father and I went through the infamous height selection. We managed to hide my 13-year-old brother, who was very short. Later, we were transferred to Warsaw, where we spent about six months working in the ruins of the city. There too, my brother escaped selection thanks to a neighbor who pushed him forward in line so no one would notice his height.”

Murky water (Illustration photo: Shutterstock)

Murky water (Illustration photo: Shutterstock)Death Marches and Dachau

One day, the Germans told the laborers that they must march toward Germany. “Those unable to walk were told to board trucks. A Gestapo officer whispered to us not to get on, and we understood that anyone boarding was doomed. We began to march without food or water, with a raging river flowing beside us, and we nearly died of thirst. During the march, my father collapsed, along with about half the group who couldn’t endure. After several days, we reached a forest and dug for water in the ground. We drank, but it gave us terrible diarrhea. Only when we reached the German border did heavy rain finally quench our thirst.”

After days of hunger and exhaustion, they were crammed into cattle cars bound for Dachau. “By the time we arrived, only a few barely alive people crawled out of each car. The rest had died along the way.”

(Illustration photo: Shutterstock)

(Illustration photo: Shutterstock)Forced Labor and Survival in Landsberg

A month later, Moshe was transferred to the Landsberg camp, where Jews were forced to build factories hidden in the forests. “Every morning, I had to hold my head up so I could jump from my bunk before the German officer came in to beat us awake with a rubber pipe. We carried cement sacks heavier than ourselves — if one fell, the worker would be thrown into the cement himself.”

Moshe could not endure the work and once hid among the dead bodies. Meanwhile, his younger brother was assigned to the laundry and later to the kitchen, so he could smuggle Moshe scraps of bread. Eventually Moshe was caught and locked in a cellar, but he managed to escape and was reassigned to easier day shifts in the forest, where sometimes he found mushrooms to eat.

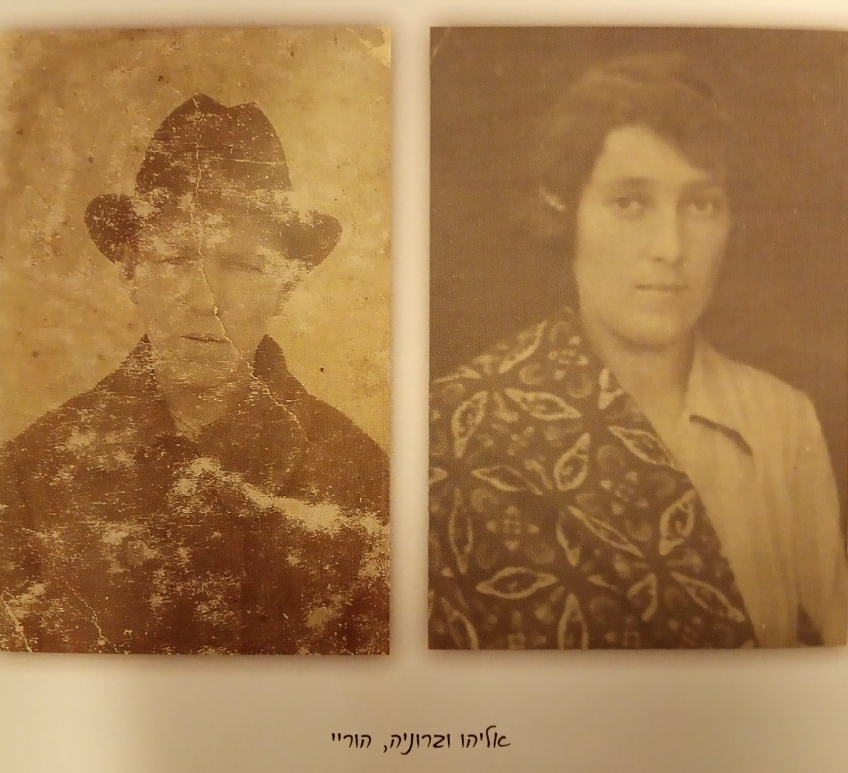

(Photo: Private Album)

(Photo: Private Album)“We Ate Grass and Weeds”

Later, Moshe was moved to Camp 4, known as a death camp: “There was no food until death,” he recalls. “We ate grass and anything we could find. Sometimes my brother smuggled potato peels from the kitchen. The day he was caught, a train arrived to take us to our deaths, and we were forced aboard. Just before we boarded, a man gave us a few potatoes. That saved us.”

Half an hour after departure, American forces bombed the train engine. “I was sick with typhus and very weak, but my brother pulled me, and together we jumped. We wandered in the forest for hours until we encountered Hitler Youth boys, who sent us to a nearby village. Of course, we were caught and taken by wagon to another camp. It was empty, but we suffered terribly there for two days until a German officer announced we would be moved. A French Jew told him we had typhus, so the Germans didn’t take us. We hid for days in the camp latrines until the Germans burned the camp. Those who survived were told by the commander that they were free, and he even pointed us to the food storage. But eating too much after starvation was deadly, and many didn’t wake up the next morning.”

Liberation and the Road to Israel

At liberation, Moshe weighed only 35 kilos and the Red Cross began treating him. He returned to Czechoslovakia and later Hungary, where he discovered a cousin had also survived — but the cousin chose to stay, was drafted into the Russian army, and disappeared. Moshe and his brother moved on to Italy, preparing to immigrate to Israel.

When they tried to come on an immigrant ship, the British detained them in Cyprus for two years. Moshe worked for the British in camp, which gave him some rest. Eventually, he and others escaped under the guards’ noses and tried again for Israel. Their boat sank, but they were rescued by Greeks, hid for a month in an orchard, and finally managed to reach the Land of Israel.

(Photo: Private Album)

(Photo: Private Album)Building a Life in Israel

Moshe was drafted immediately upon arrival and fought in the battle of Latrun. Afterward, he had nowhere to go. “They wanted to release me, but I refused. I had no home. My younger brother had already joined Kibbutz Kinneret, but I had no place to lay my head.”

When he was finally discharged, Moshe slept in the streets until the Histadrut workers’ union arranged housing. Even then, many landlords refused to rent to Holocaust survivors, blaming them for “going like sheep to the slaughter.” The only community that welcomed him were Yemenite Jews. He married a Yemenite woman, and today he has children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. “They are my greatest treasure.”

Documenting Life Stories

Moshe’s testimony is one of many preserved through Yad Sarah’s Life Stories Project. Project coordinator Anat Ben-Zaken explains:

“Many elderly people, especially Holocaust survivors, carry with them dramatic life stories but struggle to share them with family — whether because of age, emotional barriers, or fear their loved ones won’t listen. That’s why we built a volunteer system. Trained volunteers meet survivors for 12–15 sessions, record their lives from birth until their dreams for the future, and together publish a book. We see it as a way for people to process their pain, pass their stories on to the next generation, and feel closure. Often, families are amazed at the powerful life story revealed. At the end, both the survivor and the volunteer receive a copy of the book, and all stories are added to our exhibition.”