The Holocaust

The Life of Holocaust Survivor Rebecca Sandak: Survival, Resilience, and Legacy in Israel

After escaping deportation and hunger, she built a family, served Israel’s water authority, and spoke out against Holocaust denial

Rebecca Lahav (Photo: Private Album)

Rebecca Lahav (Photo: Private Album)Rebecca Sandak was born in Poland to a devoutly religious Jewish family. Her grandparents, whom she only knew through photographs, were deeply observant. Her parents, too, clung to their faith even during the war years. “They kept every holiday and every fast, even though in reality we were fasting all the time due to hunger. They instilled in us the message to hold tight to Judaism and its values. I absorbed it all.”

Her family lived in Włodawa, a town on the Bug River. With the outbreak of war in 1939, they managed to escape across the river, beginning a 10-year odyssey of survival. Those who did not flee were deported to Sobibor. “Our escape was thanks to my mother, Henia, only 27 at the time, with five children. She showed remarkable courage and responsibility.”

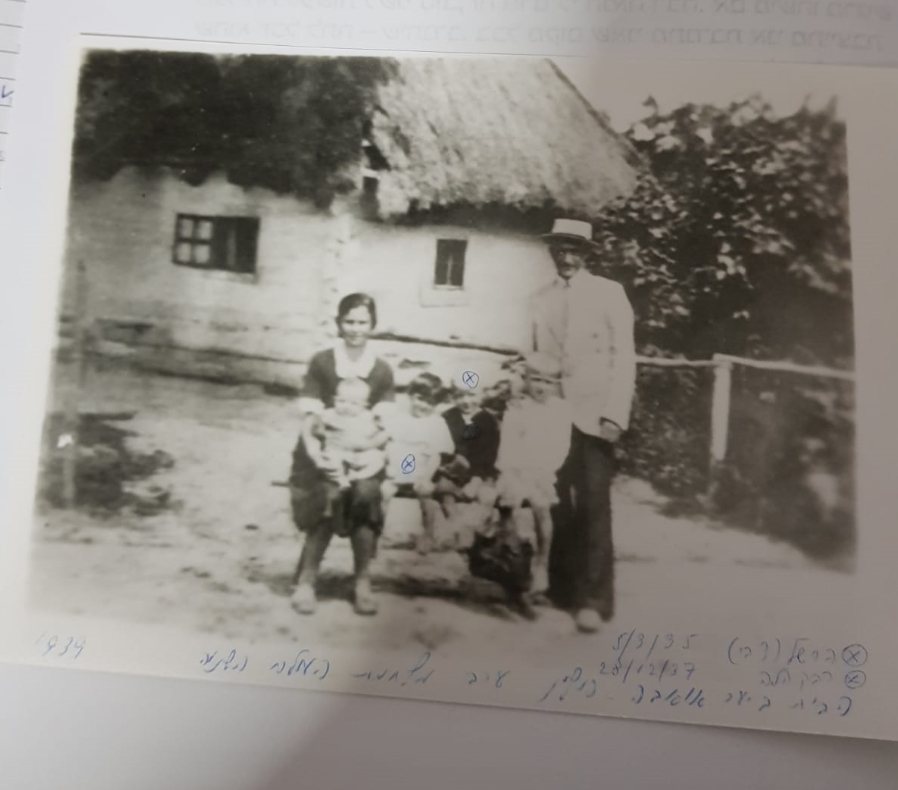

On the brink of war, the Sandak family in 1939 in front of the house her father built in Osova (Photo: Private Album)

On the brink of war, the Sandak family in 1939 in front of the house her father built in Osova (Photo: Private Album)On the Ukrainian side, Soviet forces deported them to Siberia. The men were sent to cut trees in minus 42 degrees or to coal mines. Women worked in sewing factories, and children were locked away in freezing enclosures. Rebecca recalls her mother organizing women to petition Stalin himself to bring back the men. Amazingly, a short time later, leaflets were dropped from planes announcing, “The men are coming home.”

From Siberia, the family was sent to Uzbekistan. Much of the journey was on wagons, “just like in Fiddler on the Roof.” Rebecca became temporarily blind and swollen from hunger. Her father, Nachman, a shoemaker, bartered his skills to fix shoes in exchange for flour. Thanks to a folk remedy — compresses with urine recommended by locals, Rebecca’s eyesight returned.

The Sandak family before the war (Photo: Private Album)

The Sandak family before the war (Photo: Private Album)Rebuilding a Life in Israel

After a decade of wandering, Rebecca reached Israel at age 12. “I wanted to work to support my family. I never really had a childhood. Inside, I always felt grown-up.” By age 14, she was working for the Jewish National Fund (KKL), in technical mapping for new settlements in the Galilee. Later she moved to the government water authority, where she worked until her retirement in 2001.

Rebecca became known as “the woman who measured the Kinneret.” For decades, she was responsible for recording the water level of the Sea of Galilee. “It was a great satisfaction to see the lake fill, the fresh waters blending into the old.” She also worked on water-sharing agreements with Jordan along the Yarmouk River, often serving as the trusted authority. “The Jordanians would say, ‘Whatever Rebecca says, that’s what we’ll agree to.’”

Even after retiring, Rebecca continued to volunteer at the water authority, at Poriya Hospital, and with Israel’s National Insurance. In recognition of her service, she was named an Esteemed Citizen of Tiberias.

Morning clouds March 2019 with Kinneret in the background (Photo: Private Album)

Morning clouds March 2019 with Kinneret in the background (Photo: Private Album)A Survivor’s Family and Legacy

Rebecca raised three children: two sons and one daughter, who became religious later in life. Her younger son, Shai Lahav, is a co-founder of the Israeli rock band Dr. Kasper’s Bunny Show. Her eldest son, Ofer, is a professor of astronomy and space researcher. Rebecca's children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren are living proof of survival and resilience.

Her son Shai wrote a song in English, When She Cries, inspired by his mother’s childhood as a refugee. “It’s about all children whose childhoods were stolen,” he explains. The song features her childhood photos on the cover, as a tribute to her survival and to countless others.

Flooding at Nahal Amud. Rebecca during her days at the water authority (Photo: Private Album)

Flooding at Nahal Amud. Rebecca during her days at the water authority (Photo: Private Album)Fighting Holocaust Denial

When asked about Holocaust deniers and rising antisemitism, Rebecca explained: “Humanity cannot comprehend the enormity of what happened, and maybe that’s why some deny it. They don’t understand how a people could survive, rise, and rebuild. But we did.”

What troubled her most was the fear that the memory of the Holocaust will fade as survivors pass away. “Because the first generation is disappearing, the Holocaust may become just another historical story. It won’t pierce the heart anymore. That is what I fear. Sadly, it’s a natural process in the arc of life.”

Her solution? Less reliance on youth trips to Poland, and more direct encounters with survivors. “Listening to survivors’ voices, watching their testimonies, is far more powerful than visiting empty camps. Every survivor’s story must be documented. It gives them meaning, and it keeps the memory alive for future generations. There is no future without the past.”

Rebecca Sandak’s life story is both a testimony of survival and a call to action: to remember, to record, and to never let the memory of the Holocaust fade.