The Holocaust

A Survivor’s Mission: Irena Wodislavsky’s Fight to Keep Holocaust Memory Alive

Decades after surviving the Holocaust, Irena Wodislavsky turned her home into a living museum, and hopes the torch of remembrance will be carried forward

(Photo: Private Album)

(Photo: Private Album)“It takes someone with a heart to accompany this project,” says Irena Wodislavsky, a Holocaust survivor who turned her home in Ariel into a Holocaust Memorial Museum. “I speak from my pain. It’s very important to me that the museum continues, even after I am gone.”

Irena and her late husband Yaakov — both Holocaust survivors, founded the House of Rememberance of the Holocaust and Heroism in their home. It became their life’s work: commemorating the millions of Jews murdered because of their identity, while also educating the next generations in tolerance and love of humanity.

Fewer and Fewer Survivors Remain

According to Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics, by the end of 2016 about 186,500 Holocaust survivors were living in Israel. Among them:

57,500 had been in ghettos, hiding places, labor camps, or extermination camps.

101,000 had lived in territories under Nazi control, including many born in North Africa.

28,100 were refugees forced to leave their homes due to the Nazi regime.

The majority were elderly; projections showed that by 2035, only about 14% of those alive in 2016 would remain. Women make up a growing share, especially in the oldest age groups.

(Photo: Private Album)

(Photo: Private Album)Childhood in Hiding and the Tragedy of Little Avraham

When World War II broke out in 1939, Irena was only three years old. Born in Poland, she survived in hiding with non-Jews. Her husband endured forced labor camps before arriving in Israel in 1946. Irena, hidden by a woman named Veronica, only learned she was Jewish when her father found her after the war.

One memory haunts her still. At age five, Veronica asked Irena to bring food to a Jewish boy hidden in the farm’s storage rooms. His name was Avraham, about ten years old, dark-haired, with deep black eyes. For days, Irena brought him food and played with him. Then one day, he was gone. Veronica told her his parents had taken him.

Years later, Irena learned the painful truth: Avraham had tried to escape through a window. His appearance marked him as Jewish, and locals pointed him out. A German soldier killed him on the spot. His parents, who had hidden in Veronica’s barn after escaping a deportation march, were betrayed and murdered by Poles. “To this day I think: Avraham could have grown up, married, had children…” Irena says with sorrow.

Veronica’s Courage

Hiding Jewish children meant a death sentence in Nazi-occupied Poland, yet Veronica risked everything. “She was a hero,” Irena says. “She had worked for Jews before the war and remembered them fondly. That’s why she helped.”

Even decades later, Veronica did not want recognition from Yad Vashem out of fear of her neighbors. Irena remained in contact with her, supporting her whenever possible.

Creating the Museum in Ariel

After the war, Irena immigrated to Israel, became a chemist, was widowed, and later remarried. With Yaakov, she dedicated herself to preserving memory. Their home became a four-level museum filled with rare items:

Clothing from Auschwitz

Yellow badges and armbands

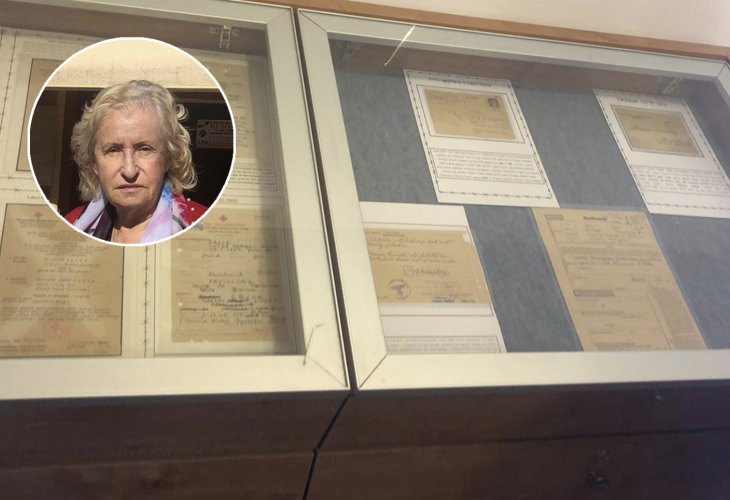

Postcards and letters from ghettos across Europe

Yaakov was a stamp collector, and at auctions Irena began buying Holocaust-era items: postcards from Warsaw, Krakow, and even Auschwitz. “The collection is a treasure that cannot be measured in money,” she explains.

(Photo: Flash 90/Rachel Kruti)

(Photo: Flash 90/Rachel Kruti)Teaching the Next Generation

Groups of students visit regularly. “Yes, the children are very curious,” Irena says. “They ask questions, they want to know. They see me and realize I was once a child who lived through the Holocaust. It fascinates them how I survived, and what I felt. That is my strength: to pass the story on.”

She insists on showing them authentic artifacts. “When children touch the objects, they say: ‘This is touching the Holocaust.’ That leaves a mark.”

What Will Happen After?

Today Irena maintains the museum with the help of just two volunteers. She has no children or grandchildren to continue the work. “I put all my strength into teaching, receiving groups, and maintaining this house. But my greatest fear is: what happens next?

“I am willing to donate the collection to another museum, if they commit to preserving it with respect. I need someone with a heart to take this on. My only wish is that the museum continues, so people can see things here that they won’t see anywhere else.”