The Holocaust

Holiness in Everyday Life: Parshat Kedoshim and the Legacy of Holocaust Survivors

Commandments, compassion, and the choice to build life after destruction

- |Updated

Returning to routine after the holiday season can be an adjustment. Rabbi Shlomo Wolbe used to say that even the “landing” after the holidays is important. He compared it to a spacecraft reentering the atmosphere — those moments of reentry are known to be very delicate. In the same way, we need to pay attention to how we land back into daily routine — carrying with us the “payload” of the holidays: our decisions, insights, and everything we discovered about ourselves, our families, and our lives.

The Torah portion of Kedoshim, provides us with guidance on how to do just that. It is one of the portions with the largest number of commandments, and in the daily reading, we encounter these instructions: “Every person shall revere their mother and father,”“Do not turn to idols,”“Do not steal, do not deny falsely, and do not lie to one another,”“Do not swear falsely by My Name,”“Do not oppress your neighbor,”“Do not rob,”“Do not keep a worker’s wages overnight,”“Do not curse the deaf, and do not place a stumbling block before the blind.” This is just the beginning.

The very name of the portion — Kedoshim (“holy ones”), reminds us that holiness is not something distant or mystical. Commentators explain that it’s about living with holiness within everyday life, including paying workers on time, respecting parents, and treating others with fairness and dignity. That’s a successful landing.

Why Not Curse the Deaf?

Parashat Kedoshim continues with its demands on us in every area of life. One particularly interesting command is: “Do not curse the deaf.” Why not? After all, a deaf person doesn’t hear the curse. Wouldn’t it be more logical for the Torah to say: “Don’t curse anyone — men, women, children, elderly”? Why single out the deaf, who, in theory, won’t even be hurt by what’s said?

Maimonides explains that the Torah isn’t only concerned with the person being cursed, but with the one doing the cursing. The verse comes to protect the soul of the speaker: that they not train themselves in anger, resentment, or revenge.

Even if the person who is cursed doesn’t hear, doesn’t know, and doesn’t feel, what matters is what’s happening to the one who speaks. Whose situation is actually worse: the driver who gets shouted at in traffic, or the one who loses his temper and yells? The referee insulted from the stands, or the fan who shouted himself hoarse?

Kedoshim teaches that when it comes to negative speech, the harm is not measured only by the pain caused to others, but also about the damage we do to ourselves by letting anger shape our words.

Breaking the Cycle: Don’t Become Pharaoh

Too often, a child who suffers violence grows into an adult who repeats it. A child who has been hurt is at risk of becoming someone who hurts others. The Exodus from Egypt sought to break that cycle: to take the Israelites from slavery to freedom — not only physically, but emotionally. To shatter the pattern where those who once suffered become the ones who cause suffering.

This message is repeated again: “For you were strangers in the land of Egypt.” It is a constant reminder of how to treat the vulnerable and the outsider. Remember what you went through, and don’t pass the pain forward.

Surviving Pharaoh doesn’t give one permission to become Pharaoh. In modern terms, surviving Hitler doesn’t give anyone legitimacy to harm others simply because they once suffered. On the contrary, it obligates us to stop the chain, to choose a different path, and to build a world based on faith, responsibility, and kindness.

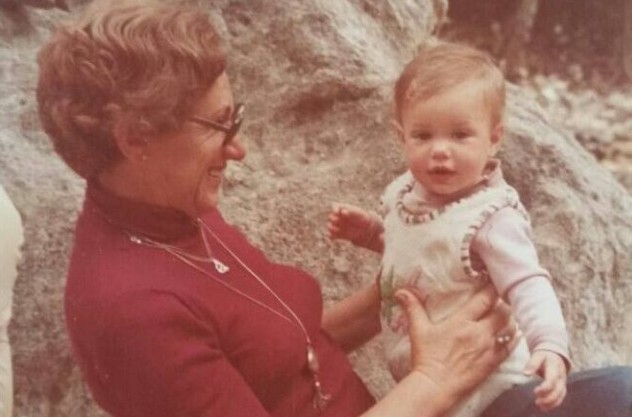

Sivan Rahav-Meir with Grandmother Zila of blessed memory

Sivan Rahav-Meir with Grandmother Zila of blessed memoryHolocaust Memory and Life After Trauma

My grandmother Ada Rozenstrauch, of blessed memory, was born in Piotrków, and survived Bergen-Belsen. She passed away at the age of 94. Until very late in life she worked as a gymnastics teacher and was a figure of strength and inspiration. After losing many family members in the Holocaust, she came to Haifa with my grandfather and built a new life, raising my father and his brother.

The Torah reading of Kedoshim reminds us: “Sanctify yourselves and be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy.” What is holiness? We often speak of the “martyrs of the Holocaust” — the six million murdered. But there was also immense holiness in the decision of survivors to cling to life, and to not drown in bitterness.

Some explain that this is the very essence of the Kaddish prayer: “May His great name be magnified and sanctified.” After devastation, we must continue to magnify life, to bring God’s presence into the world, and to sanctify reality itself.

Today, when families tragically lose loved ones, an entire nation surrounds them with care and solidarity. After the Holocaust however, millions of survivors — each one an orphan, bereft of parents, siblings, home, had no such national embrace. And yet, they chose to rise from the ashes: to build, to plant, to teach, to learn, and to love.

From the depths of evil and destruction, they added goodness and holiness. In this sense, survivors themselves — including my grandmother Ada, are truly among the Kedoshim, the holy ones of the Holocaust.