Torah Insight for Parashat Bechukotai: Breaking the Cycle

Discover why the prohibition against theft is written in plural form and understand the reason for the prolonged exile

(Photo: shutterstock)

(Photo: shutterstock)"Close the window," grumbled one of the passengers on the bus to the person sitting in front of him, "it's cold outside."

"And if I close the window," teased the passenger who wanted fresh air, "will it be warm outside?"...

* * *

In Parashat Bechukotai, the curses appear as a conveyor belt, each one following the previous, and each being a continuation of the former. These matters are indeed purposeful and contain lessons and foundations like the entire Torah. However, in this context, we will try to focus on one point where we all need strengthening, some more than others.

"And the sound of a driven leaf shall chase them... and they shall stumble one upon another as before the sword, when none pursues." There is no doubt that this is a terrible curse. Let us try to examine the depth of this verse - according to Rabbi Ephraim Shlomo of Luntshitz, author of "Kli Yakar" - and understand the connection between the fact that Israel will hear "the sound of a driven leaf" rustling in the wind and flee from it, and the subsequent fact that "they shall stumble one upon another."

Rabbi Moshe Yitzchak Darshan, "the Maggid of Kelm," related: I have always wondered why the Torah defined the prohibition against stealing in plural form, "lo tignovu" (you shall not steal, plural)! Why not say it in singular form, "lo tignov" (you shall not steal, singular)? [The prohibition "lo tignov" in the Ten Commandments refers to "kidnapping" - a person who steals people to sell them as slaves. "Lo tignovu" refers to property].

Until I witnessed an incident - the Maggid of Kelm told in his sermon to the townspeople: My neighbor had a chicken stolen from her yard. Instead of going into the house and telling her husband about the theft, so he could go and complain at the police station in the nearby town, my neighbor did something else - she entered the yard of her neighbor to the left, quietly stole a chicken from there, and returned to her yard as if nothing had happened...

(Photo: shutterstock)

(Photo: shutterstock)The neighbor who had just had a chicken stolen from her, of course, knew nothing about it. She went out to her yard and found that she was missing a fowl. And what do you think? That she went to tell her husband? Not at all! She turned to the yard next to her on the left and took a clucking bird from there and quietly left.

The third neighbor took from the fourth, and the fourth from the fifth, until at the edge of the town, after two or three days, the voice of a poor peasant woman was heard lamenting that a chicken had been stolen from her yard...

That is why the Torah warns in plural form, "lo tignovu." Even if something was stolen from you, you have no permission to steal from others who will then steal from their neighbors and so on.

Now let us approach the words of the "Kli Yakar" and this is the essence of his words: When people are exiled from their land, they tend to unite and comfort each other, to provide emotional support and be brothers in adversity to one another. But the people of Israel, unfortunately, behave differently, and thus Achiya the Shilonite prophesied about Israel: "And Hashem will smite Israel as a reed is shaken in the water."

And what is this curse? Every reed that is pushed by the wind in the water pushes against its neighbor. So each reed is pushed twice, once by the blowing wind and once by its neighbor that is pushed against it. Similarly, Israel in their exile, instead of encouraging one another and saying to their brother "be strong," they are pushed by the gentiles, and as a result of the "pushes" of exile, they push one another, and then that person pushes another - until the last of them falls.

This explains the connection between "and the sound of a driven leaf shall chase them" referring to the decrees of exile, and "they shall stumble one upon another" meaning that each one will push his fellow. And since Israel are connected to each other at their root, the pushing does not stop with the last one; it returns spiritually to the first one...

And why does this happen? The "Kli Yakar" explains a depth in the verse, revealing that this curse is not a punishment from heaven. It is a consequence of inappropriate behavior among ourselves: The Sages in the Talmud interpret the verse "and its leaf shall not wither" as referring to "the casual conversation of Torah scholars," which also requires contemplation and study, because it is not idle talk.

We see that a "leaf" is compared to conversation, and it has importance.

Unfortunately, the "Kli Yakar" makes a painful and truthful comparison: we talk and chatter in the streets of the city about what we heard about so-and-so, and about such-and-such. These words of gossip spread like fire in a field of thorns, along their way they cause casualties, and sow hatred and division.

This is the reason why Israel is pushed twice in exile: once from the decrees of the gentiles and the second time - we cause to ourselves through the evil tongue that knocks people down like a domino effect, one after another.

* * *

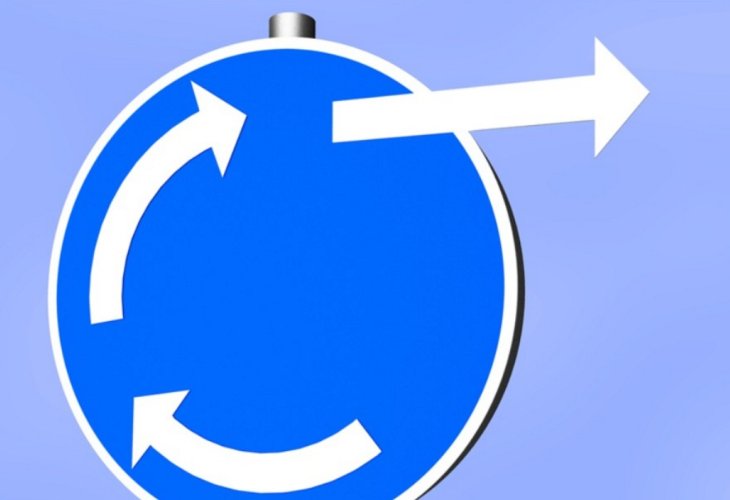

When we are convinced that we are allowed to behave inappropriately toward others because "they pushed me - so I will push too," we should remember that at the end of this process, that push will return to us. But if we restrain ourselves and avoid pushing, we can "break the vicious cycle."

Refraining from one forbidden word may seem to us as if it doesn't affect our surroundings. It's true that outside it will remain cold, but "closing the window" will make it pleasant for us.