"Inmates Walk Here with a Kippah and Tzitzit, It's Not a Show"

Rabbi Yaakov Meir Elkoubi, the rabbi of Ketziot Prison, often meets inmates with tzitzit and a kippah asking how to strengthen themselves, and he's not surprised. He mentions a growing spiritual awakening at the prison. How does this relate to the book he is about to release?

(Photo: David Cohen/Flash90)

(Photo: David Cohen/Flash90)When Rabbi Yaakov Meir Elkoubi entered the synagogue at Ketziot Prison the day after Simchat Torah and saw it full of praying inmates—wearing orange uniforms, seated on wooden chairs, awaiting the start of the prayer—he rubbed his eyes in disbelief. In the next moment, he rubbed them again, this time out of sheer excitement.

"There are always inmates who come to pray," he notes, "but usually it's hard for us to gather a minyan. Yet this time the synagogue was packed full. I think not even on Rosh Hashanah were there so many worshippers."

Ketziot Prison is located in the sands of Chalutza in the south and is considered the largest prison in Israel, divided into different wings. "You might think inmates would be preoccupied with themselves and serving their sentences, uninterested in the outside conflict, but it turns out they're fully aware, very concerned, and also pray and strengthen themselves, feeling it's the least they can contribute," shares Rabbi Elkoubi.

From the Kolel to the Prison

Until about a year ago, Rabbi Elkoubi was a kolel student, living in Sderot. He studied at the local kolel and simultaneously invested in rabbinical studies. After nine years of study, he received certification as a regional rabbi and thereafter sought a significant religious role where he could apply the extensive Torah knowledge he had acquired.

It was during this time an offer arrived for him to serve as a rabbi at Ketziot Prison on behalf of the IPS (Israel Prison Service). "Initially, I hesitated a bit," he admits, "but after deep thought, I concluded that through this position I could help people who have reached the lowest and darkest point in their lives. If I could establish a close and proper connection with them, I could provide the right and precise assistance. It was clear to me this was a mission, and this understanding motivated me to take on the role."

It's undoubtedly a significant change—from learning in a kolel to being with inmates!

"Certainly. It was a drastic change for me. Until then, I was a kolel student living in a bubble, surrounded by others who looked and behaved like me. Suddenly, I switched the entire atmosphere and was surrounded for hours each day by inmates serving sentences, typically having been expelled from all possible frameworks. You could say it's a complete opposite. But I prepared myself well beforehand, and to some extent, I can say I've been positively surprised. It turns out that even people in their hardest situations can show their greatness, seeking advice on halachic topics, overcoming themselves, or making difficult decisions even if it's not easy for them. I encounter these situations all the time, especially recently during the conflict, where it seems everyone is trying to strengthen themselves."

There is a well-known phenomenon of inmates who, upon entering prison, start wearing a kippah. Do you think it's genuine or a show?

"I don't know what's in everyone's heart, but here at Ketziot Prison, I definitely meet inmates where, at least for some, it seems very genuine indeed."

On the topic of tzitzit, Rabbi Elkoubi adds that as part of the inmates' work, they also dedicate special hours each day to tying tzitzit, which are then passed on to soldiers. To differentiate, they are also responsible for building coffins, which, unfortunately, are also needed these days."

(Photo: Moshe Shai/Flash90)

Learning from the Inmates

What is your official role as the prison rabbi?

"In addition to having halachic authority to rule on necessary laws, I also deliver lessons and am in charge of prayers, serving as something of a father figure," Rabbi Elkoubi explains. "I think it's easier for inmates to connect with the rabbi and share what's happening to them, rather than sharing with professional figures like a welfare officer, a social worker, or a unit commander. They see the rabbi as a wise person, and sometimes it's important for them to hear what the Torah says about their situation. I try to use my position, quoting from the sages on advice in times of crisis and downfalls, and ultimately, I see that at least some inmates connect deeply to the words. As far as it seems, it's a genuine strengthening that comes precisely from the state of being in prison, with harsh conditions and being so far from freedom. I don't know what will happen to these inmates after they're released, but it's clear that when they're here they experience strengthening."

During the past two months, Rabbi Elkoubi has also experienced genuine interest in his situation from the inmates. "They are aware that I live in Sderot and are very curious about my situation and my family's state, constantly asking how my wife and I are doing and how the young children are managing."

And how are you managing? Did you evacuate from the city?

"We left Sderot the day after Simchat Torah. Initially, we were relocated to the Reut girls' high school in Petah Tikva, and these days we reside in a guesthouse in Moshav Beit Meir, near Jerusalem. This requires me to travel about two hours each way to work. It’s not easy at all, but I do it with love, seeing how happy the inmates are to see me. It’s clear to me that it has a positive impact."

Everyone and Their Own Prison

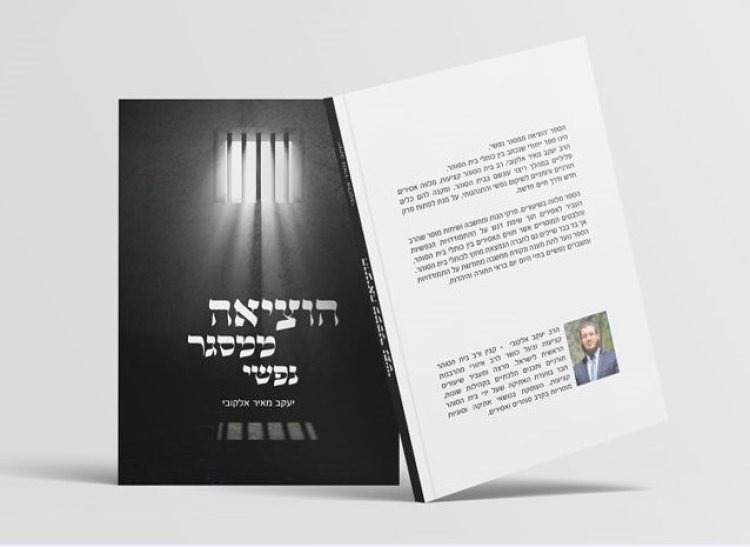

These days, Rabbi Elkoubi is preparing to publish an extraordinary book in which he shares the life activities within the prison combined with lectures and moral words he delivered to inmates over the past year.

"This will be the third book I'm publishing with the help of Heaven," he notes. "And the truth is, I see it as a mission. People outside don't really know what goes on within the walls of the prison, how the inmates cope, and what their worldview is—all while I believe that from their situation, there is so much to learn. In essence, we all feel down at times when we face crises and need a conversation to empower and strengthen us. True, we're not prisoners in a penal institution, but each of us has their own 'emotional release from captivity.'"

The book, which is about to be released in the coming days as Rabbi Elkoubi points out, is divided into five chapters, discussing questions and answers about dealing with life's crises. Later, it also provides directions for making right choices, featuring a whole chapter with parables and moral lessons, and another chapter based on discussions Rabbi Elkoubi delivered to inmates on the Ten Commandments.

"These are conversations I conducted jointly with the education officer," he explains. "Each time, we discussed a different commandment and developed it from various angles. It was fascinating for the inmates, who may have thought they knew what 'You shall not steal' or 'You shall not murder' means, but when we delved into each commandment for almost an hour, it provided a much deeper perspective and intriguing insights."

Do the inmates know that the book is about to be published?

"I haven't told them yet; it's a surprise for them," explains Rabbi Elkoubi, with a tone of affection for the inmates. He pauses for a moment and then adds sincerely: "Sometimes I feel like I learn from the inmates no less than they learn from me. Coming from such a protected and secure place, not truly understanding what people are going through in life, I get to know such complex stories, learn to thank Hashem for having blessed me with different experiences, and also understand that one should never judge anyone until reaching their place. Because I'm not sure that if I had gone through the life's challenges the inmates face, I would have been able to withstand it. There is no doubt this work has changed me and taught me a lot about the essence of life."

(Credit: Courtesy of IPS)