"Teachers Abused and Punished Me Because They Didn't Understand I Couldn't Learn"

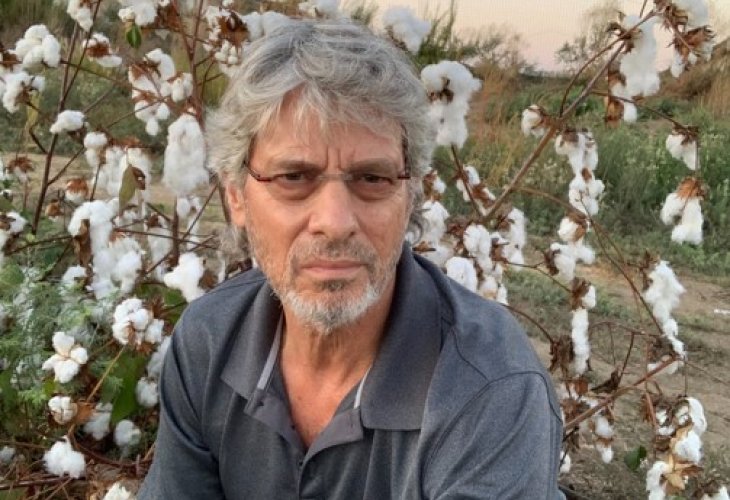

Shmuelik Tasler was a brilliant and witty young man with a learning disability, but he couldn't learn. His teachers failed to understand until the day he decided to teach them a lesson. Now, fifty years later, he revisits his life's story and pleads: "Teachers, look for the abilities in your students, because they are always there."

It's hard to talk to Shmuelik Tasler and hear about his school experiences from more than fifty years ago. Tasler grew up in Kibbutz Yavne, where he also received his education—or as he prefers to say, he was "somewhat educated"—during his elementary school years.

"It may surprise that a 68-year-old remembers every detail from his school days, but that's the reality. These memories have become tangible parts of my life," he says painfully. "That's also why I'm sharing my story, because I feel it carries a significant message for parents and teachers. I hope to save at least one child like me among so many in similar situations."

Wanting, But Unable

Tasler entered first grade like all the other kibbutz children and managed to cope until sixth grade. "I didn't learn a word, but the teachers somewhat turned a blind eye," he recalls. "But in seventh grade, serious learning began, along with demands and punishments. Teachers made it clear time and again that a child who doesn't study or do assignments is lazy and must be punished. They weren't trained educators but community members fulfilling a role, and they knew how to punish both physically and verbally."

Tasler chooses not to detail the types of punishments but insists none of them truly helped him learn or changed his situation. "I didn't learn a word, didn't take exams, and didn't do a thing—absolutely nothing," he says. "Even when asked to bring my parents' signatures, I didn't comply. When I brought home negative tests, I faced yelling, as my parents always believed the 'teachers were right.' It was easier to forge a signature or not bring a signed test at all."

Did the teachers think they were helping you with these punishments?

"The main issue with the teachers was that they assumed I didn't want to learn, not that I couldn't. They thought I was lazy and believed punishments would change me. Only years later, when my attention deficit disorder was diagnosed, was I able to understand why those punishments didn't help. When a child has severe attention issues and a learning disability, standing them in a corner doesn't help, nor do slaps or ear pulls. How can a child write 'Song of the Sea' a thousand times or learn prayers by heart when they're incapable?"

On the Railway Tracks

"My teachers really tried to educate me," stresses Tasler. "They went out of their way, even giving me extra lessons in the afternoons instead of letting me play with friends. I went to a teacher who tried to help with homework, but he freaked out when he realized I hadn't even copied the questions from the board. The last session ended with a strong ear pull, and he said, 'Go away and don't come back without your homework.' Leaving his house agitated, I felt blood dripping from my ear, which was beyond my tolerance. I decided it was time to involve my parents. As I walked, contemplating the speech I'd give them, I realized no one was home.

"Unable to wait and driven by desperation, I did something drastic. I tore a page from a notebook the teacher had inscribed 'Don't come back without homework.' I penned my own note, put it in my bag, and stormed off to the railway tracks, a fifteen-minute walk away. I focused entirely on my dreadful plan until I reached the tracks. Then, at the last moment, a memory of my mother—a Holocaust survivor—flashed in my mind. She always said, 'We did everything to live,' and as I heard the approaching train, her words hit me, and I rolled to the side on the gravel. The ground shook, the train passed, and I stood up, dusted myself off, and returned to the Ashdod junction. Ignoring the car horns around me, I continued until I crossed the intersection, driven by a need to teach everyone a lesson. It was the weekend, and I decided to disappear. Staying with a friend in Kfar Mordechai for Shabbat, his family welcomed me warmly, offering a sweet sense of victory. Apparently, I taught the adults a lesson, as my disappearance caused a stir in the kibbutz. But before panic set in, my friend's parents contacted mine and calmed the situation."

A positive thing emerged: the message got through, and until the end of elementary school, teachers left Tasler alone. In high school, unable to participate in most classes, they gave him a simpler path—working in the fields. "I loved working," he remembers. "I got my tractor license young, tilled the land, and felt good about it. I occasionally attended classes, mostly joining during breaks and trips, so socially, I wasn't affected, but I didn't dedicate a minute to studying."

Tasler insisted on living like his peers, even joining the paratroopers and achieving the unthinkable by passing officers' courses ("I'd rather not detail all the hardships," he notes). "I always had a strong desire to be like everyone else, fighting tooth and nail for everything I wanted despite the challenges and failures."

"Save the Children"

Tasler pauses, taking a deep breath. "I could look at life from the vantage of my respectable 68 years and say 'I won.' After all, I've built a family, have an extraordinary wife, three sons, and a daughter who will marry soon. Life is great; I've learned computer and mobile device repair, succeeded in my work, and fulfilled many dreams. Hashem granted me much kindness, but I'm still haunted by those teachers who taught me failure at age 12. I can't shake the sense of deprivation from painful school memories.

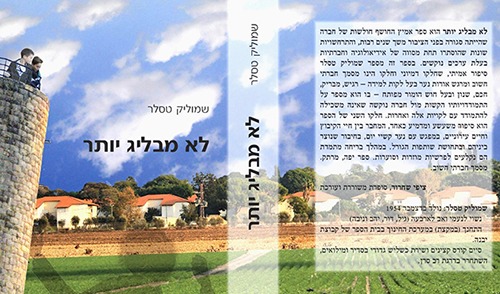

"Every time I remember my near tragedy on the railway tracks and my mother's saving words, my heart aches because 40 years later, I couldn't save my son, Dorik, who suffered similar attention and concentration issues. Despite fighting for him, wanting him to know I was there, I failed. These hard feelings led to writing the book 'No Longer Holding Back,' sharing my life story with some alterations and fictional elements to convey the message and ensure no more children endure what I did."

Tasler emphasizes how difficult it is to discuss the topic and expose the pain. "But now, as school starts, conveying this message to parents and educators is crucial: if you see a child struggling academically, regardless of diagnosis, allow them to develop their inherent abilities, because there's no child who's not good at anything. We can always identify their strengths. However, don't remove them from frameworks; don't make them feel out of place because experiencing the opposite extreme isn't beneficial either. Children and teenagers need frameworks to save them and ensure they feel safe. Our responsibility as parents and educators is to balance a structured environment with recognizing a child's difficulties—not to label them as 'struggling' but to create opportunities for them."

Do you think educational staff are aware of these issues?

"Fortunately, awareness is rising. I take great interest in what happens in my grandchildren's schools, noting the adapted courses and programming. I wish we had such opportunities or that Dorik did. It's a completely different world, and I'm confident that such children can find their place and thrive."

Tasler wishes to end on an optimistic note: "I thank Hashem every day for my life, as they are filled with meaning and content. I live in the kibbutz I love, continuing my mother Hana Tasler's legacy—she's a 98-year-old Holocaust survivor living nearby. My son recently moved here, and my daughter plans to as well. I have grandchildren and much joy in life. These are the best lives I could wish for."