"At 13 I Couldn't Read, Now I Have a Master's Degree"

Zahava Deslin immigrated to Israel from Ethiopia without knowing how to read or write, and unfamiliar with Hebrew. She had a clear goal: to learn and succeed. Today, as Director of Excellence at Kiryat Malachi Municipality, she is certain: "There is no such thing as a child who cannot achieve."

In the circle, Zahava Deslin (Background: Tomer Neuberg / Flash 90)

In the circle, Zahava Deslin (Background: Tomer Neuberg / Flash 90)What is it like for an orphaned girl who immigrates to a new country and is hospitalized? Or, for a girl from rural Ethiopia, unfamiliar with the written word or even using utensils, who suddenly arrives in Israel, expected to integrate, learn Hebrew, and become just like everyone else?

Consider these scenarios and you'll understand the unbelievable story of Zahava Deslin, who came to Israel in 1992 as a 13-year-old orphan from both parents, after a long journey starting from her village in the Kwara region of northern Ethiopia.

But there's further inspiration in Zahava's story, as she currently lives in Kiryat Malachi and is a mother of four. She holds a Master’s in Education and serves in a senior municipal role. “I share my story so people understand that you can go from zero to one hundred; it’s all about our determination, and of course with Hashem’s help," she clarifies.

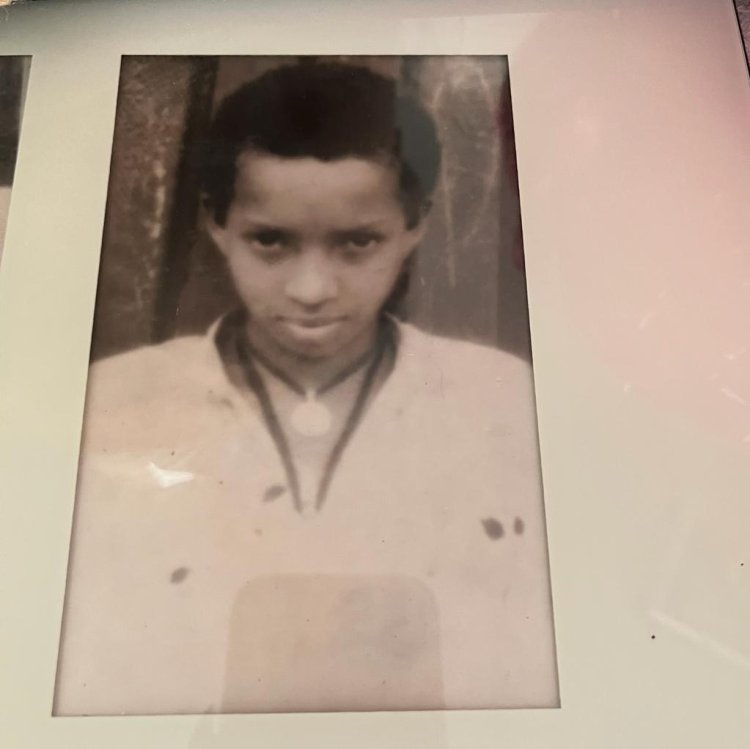

Photo of Zahava as appears in her immigrant certificate ('This was my first photo')

Photo of Zahava as appears in her immigrant certificate ('This was my first photo')

Months-Long Journey

Zahava was born in an Ethiopian village, growing up in a devout family considered one of the oldest in the village. “We are seven siblings," she recalls. "Our parents passed when I was six, and our grandparents raised us."

Her grandfather died a year before their immigration to Israel. Zahava remembers how he would describe 'Yeruslem' (Jerusalem) to them. "He'd draw in the sand, depicting a country surrounded by enemies, made entirely of gold and silver, promising it will be good for those who make it there, but acknowledging the difficulties because of the country's hardships. He was realistic, unlike others in Ethiopia who thought problems would vanish upon arrival. He often told us, 'I’m not sure we elders will make it, or if we do, adapt, but you young ones will thrive.’”

Zahava notes they always knew they would one day go to Jerusalem, so the decision to embark with about ten families, including her immediate family of four siblings and their grandmother who oversaw the months-long journey, came without surprise.

Immigrant from Ethiopia (Photo: Michal Fattal / Flash 90)

Immigrant from Ethiopia (Photo: Michal Fattal / Flash 90)Did you walk the entire way for months?

“Yes, we walked, but had a few donkeys and a horse for the weary. Grandmother mostly stayed on the horse due to her age and asthma, while we children ran ahead, spurred on with stories of 'Yeruslem’ and promises of candy if we hurried, feeling eager and unstoppable.”

What about food and water?

“The adults organized dry food, and although some had more, everyone shared. Water was scarce, relying on rivers along the route. We’d constantly ask, 'When will we reach the river?' and they reassured us to keep going, promising we would find it soon, invigorated by each discovery to drink, bathe, and rest before moving on. We mainly walked by day; by night, we’d sleep on the ground until dawn.”

Throughout the journey, Zahava stresses the Divine assistance. “Unlike other families crossing the Sudanese border, facing immense dangers, our ‘kasim’ (rabbi) advised the Addais Ababa route. Though longer, it lacked the deadly fear of Sudan. We lost only one child, a 4-year-old, a relatively low toll compared to others crossing through Sudan.”

New Immigrant (Photo: Michal Fattal / Flash 90)

New Immigrant (Photo: Michal Fattal / Flash 90)

Jerusalem Lights

After months on foot and then a truck ride, they reached Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital, prepared to wait their turn for a flight ticket. “I was there only two weeks,” Zahava recounts. “I had a throat infection, suffering a lot. They informed us about available tickets and advised my grandmother of our departure. Though initially reluctant, the agency assured her we’d be state wards upon arrival, urging not to delay us. She agreed, and thus, my siblings and I ascended. My fourth sister came later, as a newlywed with her husband.”

What do you recall from the flight to Israel?

“Mostly throat pains. I laid on the plane floor, occasionally peeking up at glimpses of Israel’s houses, lowering my head back down. They attempted to teach me to eat with a fork, foreign to us as we used our hands.”

Upon landing, buses awaited to take us to the boarding school, where from the window, I marveled at the lights and thought, ‘This must be Yeruslem—lights and gold.’ Upon arrival at the boarding school, they quickly noticed my swollen throat, unable to drink or eat, leading to immediate hospitalization, my harshest journey trauma."

Why was the hospital experience so challenging?

"Imagine being alone, surrounded by doctors not speaking a word of Amharic, nor I of Hebrew. They gestured for me to eat and drink, yet I found the unrecognizable food unbearable, served unfamiliar fruits like grapes and peaches; only oranges, unavailable in the summer, were known. The unfamiliar smells made me nauseous."

Staff from the boarding school visited, explaining the doctor’s orders for long-term care unless I began eating. They advised that upon discharge, a guide will announce 'Hofim,' our boarding school's name.”

Each day, I'd gesture refusal at the offered food, walking the corridors, anticipating the guide’s magical word 'Hofim,' yet awaited in vain."

How did you find strength during such loneliness?

“Two girls my age admitted nearby brought me to a kiosk, holding up candy, asking ‘Want?’ I repeatedly said ‘No,’ yet their gesture warmed my heart. A miraculous reunion with a relative who immigrated months earlier invigorated me, as he retrieved my favored 'injera' and sweet grape juice, replacing the frightful fizzy soda. Relishing familiar tastes bolstered my spirits, even aiding pill consumption to recover. A week later, the awaited guide proclaimed ‘Hofim,’ signaling my release, with my sole Ethiopian dress packed."