Personal Stories

The Remarkable Life Story of Oded Zand: Overcoming Disability, Adoption, and Adversity

How a child born with severe disabilities transformed hardship into purpose, strength, and spiritual inspiration

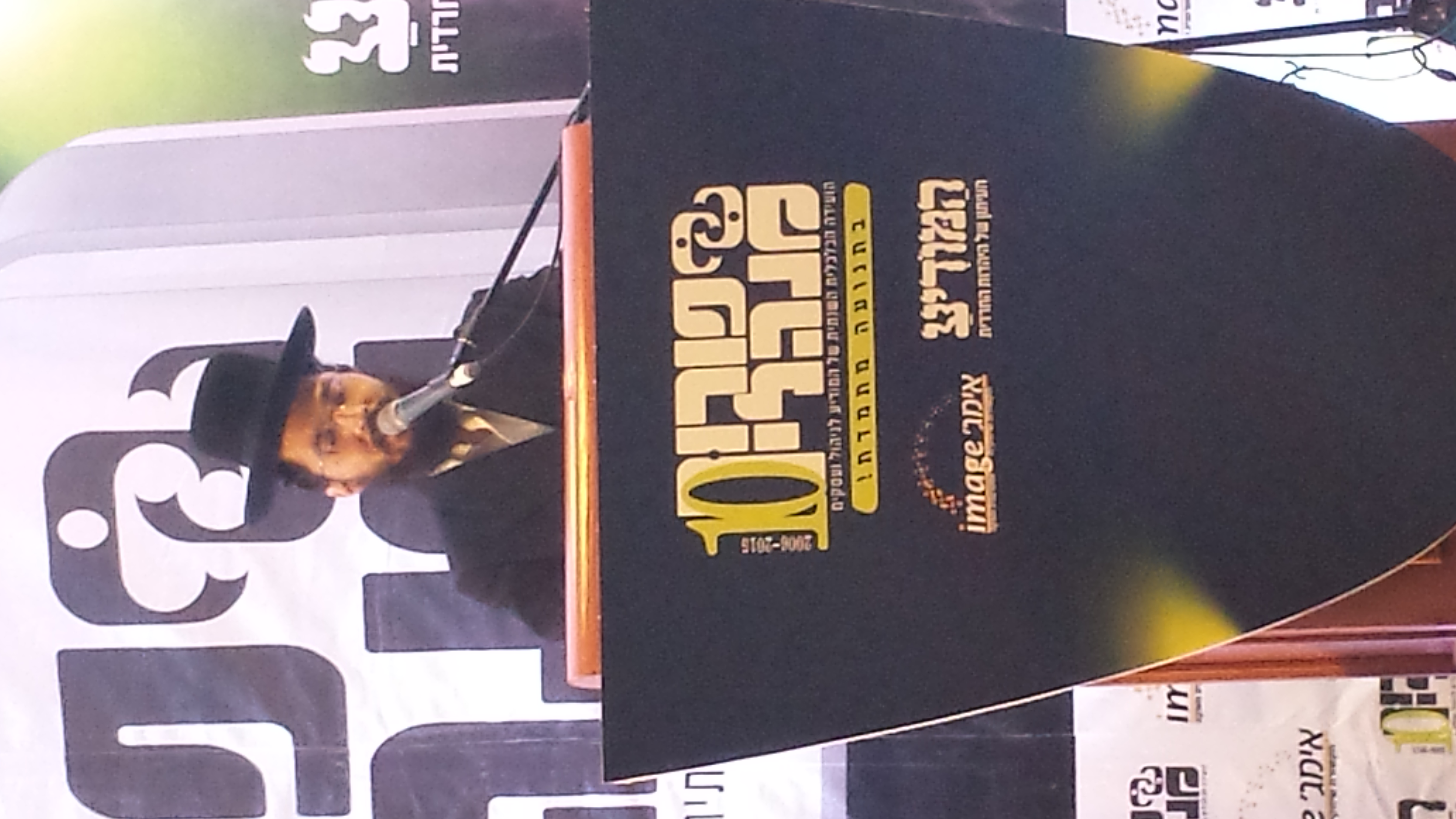

(Photo: Courtesy of the Interviewee)

(Photo: Courtesy of the Interviewee)

Imagine a newborn infant lying abandoned in a hospital, born without fingers and with disabilities in his legs. What are the chances that such a child would one day succeed in life? Yet this is exactly the story of lecturer Oded Zand.

Zand, who recently published his book “With My Zero Fingers,” in which he recounts his life story, says in a conversation with Hidabroot: “All my success comes from the guiding hand of Divine Providence that accompanied me every step of the way.”

Born Into Challenge: “My Parents Chose Denial”

Zand was born in Soroka Hospital in Be’er Sheva. “I was born without fingers, and with disabilities in my legs,” he shares. “I was my parents’ second child, and they were completely shocked. They expected a healthy baby and never imagined bringing a child into the world with such difficulties.”

Their response was extreme: “Just 24 hours after my birth, my mother disappeared from the hospital, leaving me alone in the nursery — a one-day-old infant.”

Looking back, Zand judges them generously. “These were different times,” he explains. “There were no frameworks or support systems for children with medical challenges. They were overwhelmed, and I hold no resentment. As a believing Jew, I am certain that this was exactly what Divine Providence intended for me.”

Hospital staff struggled to decide what to do with him. Attempts were made to find an adoptive family, but no one came forward. “People want to adopt a child who they believe will thrive. No one seeks out a child with disabilities,” he says calmly.

(Photo: Courtesy of the Interviewee)

(Photo: Courtesy of the Interviewee)A Failed Adoption — Then a Miracle

“A religious nurse at the hospital decided to suggest me to her aunt and uncle in Bnei Brak,” Zand recounts. The couple had been childless for 15 years. The nurse gently encouraged them to consider the adoption as both a mitzvah and a source of joy. They agreed.

But before the adoption was finalized, something astonishing happened: the couple suddenly found themselves expecting a child.

“We don’t understand Heaven’s calculations, but perhaps it was in the merit of the kindness they intended to do,” Zand reflects. Their doctor advised postponing the adoption — and the plan was cancelled.

Yet Providence intervened again. The aunt’s brother shared the story with a colleague — a Holocaust survivor, a righteous man with children of his own, who decided to adopt Oded purely as an act of kindness.

“They also knew,” Zand explains, “that if no Jewish family adopted children like me, non-Jewish families would — with the intention of raising them in their own faith, Heaven forbid.”

At six weeks old, Oded was brought home to his new family in Bnei Brak. “They already had five children. I became the sixth.”

A Father of Greatness and Silence

Zand pauses to honor the man who raised him. “My adoptive father passed away three years ago at age 93. My mother, may she live and be well, still enjoys seeing the blessing in my life.”

His father, a Ger chassid and a survivor who buried his own parents during the Holocaust, rarely spoke idle words. “He would wake up at 3 a.m. to serve his Creator,” Zand recalls. “He never complained. He rebuilt his life from ashes.”

He laughs as he adds, “He hated idle chatter so much that nobody wanted to volunteer with him…”

A Courageous Kindergarten Teacher Who Saw Beyond Disability

“When my mother tried to enroll me in kindergarten, the teacher panicked and refused. She said I would hurt the reputation of the private kindergarten. My parents had no choice but to keep me home.”

Eventually, a kindhearted Chabad teacher named Tova Hershkovitz agreed to take him — on one condition: he would not come on the first day, so the children could adjust without fear.

It worked. “She sat me beside her and gave me small jobs. The children grew to love me. Parents told her their kids came home saying, ‘There’s a boy in our class with no fingers — and he can draw!’”

(Photo: Courtesy of the Interviewee)

(Photo: Courtesy of the Interviewee)The Stares, the Pain, and the Prayers

Although Zand adapted well, the world often responded with confusion or discomfort.

“When I walked in the street or entered a synagogue, children stared at me like I was an exhibit. If I was alone, it was painful. I would silently pray for strength. Those moments actually brought me closer to God.”

The challenges continued in yeshivah and later during the matchmaking period. “I married at nearly 25. My friends married easily; my proposals were often unsuitable. It wasn’t simple.”

He used the waiting period to earn semichah (rabbinic teacher certification) and later published a book from those studies.

“My Disability Became My Mission”

Zand now volunteers in hospitals, visiting people who have lost limbs.

“There is a huge difference between someone born without limbs and someone who loses them. I try to give them hope, to show them life is still possible.”

One particularly emotional meeting was with a family whose baby was born without fingers and with leg issues, just like him. “They were afraid to take him outside. They even avoided family events. I told them gently that hiding him would only harm him. ‘If my parents had hidden me,’ I said, ‘I wouldn’t be who I am today.’”

Moments of Humility and Humor

He recalls the embarrassment of being asked to roll the Torah scroll in synagogue — a job he physically cannot do.

“Usually I would step out before the rolling. Once I didn’t make it. When I declined, an older man scolded me for not honoring the Torah. After he insisted, I pulled my hands out of my pockets. He turned red and walked away.”

“Judge Others Favorably — We All Have Trials”

Zand concludes softly: “Whatever challenge a person receives, it is because Heaven knows he can overcome it. Don’t live in the past. Live the ‘now’ and embrace the mission God gave you.”