The Photographer's Daughter: 'Unearthing the Photos, It's a Dream'

Batya Lussos, 'the daughter of the photographer from Yanova,' was only nine years old when World War II erupted. She miraculously survived the 'Children's Aktion' in Kovno and endured the harsh life in the ghetto. Now, she unveils in a unique exhibition the rare photographs taken by her father, along with the incredible stories behind them.

In circle: Batya Lussos (background photo: shutterstock)

In circle: Batya Lussos (background photo: shutterstock)"At nine, I stopped being a child," says Batya Lussos, pausing. It's a significant silence expressing feelings words cannot convey. How can one explain what happens to a young child as a world war breaks out, innocence evaporates, replaced by overwhelming fear and helplessness?

Recalling those days isn't easy for Batya, but as she attests, they are part of her essence. "When World War II broke out, I instantly became an adult," she describes, "I had no dolls, no games, not even friends, because we were moved to the Kovno Ghetto, and I was almost the only child who survived the Children's Aktion. I walked around with the feeling that at any moment I could die, not to mention the terrible hunger. To illustrate this, it's enough to say that my father went into the ghetto weighing 100 kilograms and came out weighing 39 kilograms."

Batya, before World War

Batya, before World War

Innocence Lost

Nearly eighty years have passed since the war's outbreak, and Batya claims to remember everything. She remembers her pounding heart and trembling legs at the sound of Nazis approaching;; she also recalls planning to shut her eyes when the shooting would start.

But Batya also remembers what was just a few years earlier when she and her family lived in Yanova with a sweet and innocent routine. "In those days, Yanova was a large Jewish community of about 2,700 Jews," Batya notes, "Our family was well-known, mainly because of a photography studio called 'Union' established by my father, the photographer Tuvia Joffe. Many people from all over – Jews and non-Jews – came to be photographed there."

Batya grew up in her father's studio, and these years remember as especially sweet and experiential. "We had a large, spacious house," she describes, "The second floor was for living, and the bottom floor was for the studio. Many important people came, some to be photographed and others because they loved Dad and wanted to be with him. The waiting room was always full. I used to walk among the people and mainly loved entering the darkroom with Dad. It seemed like magic when Dad would go in with films and come out with photos. During the work, he would sing in Hebrew and Yiddish. He had such a pleasant voice, and I would join him."

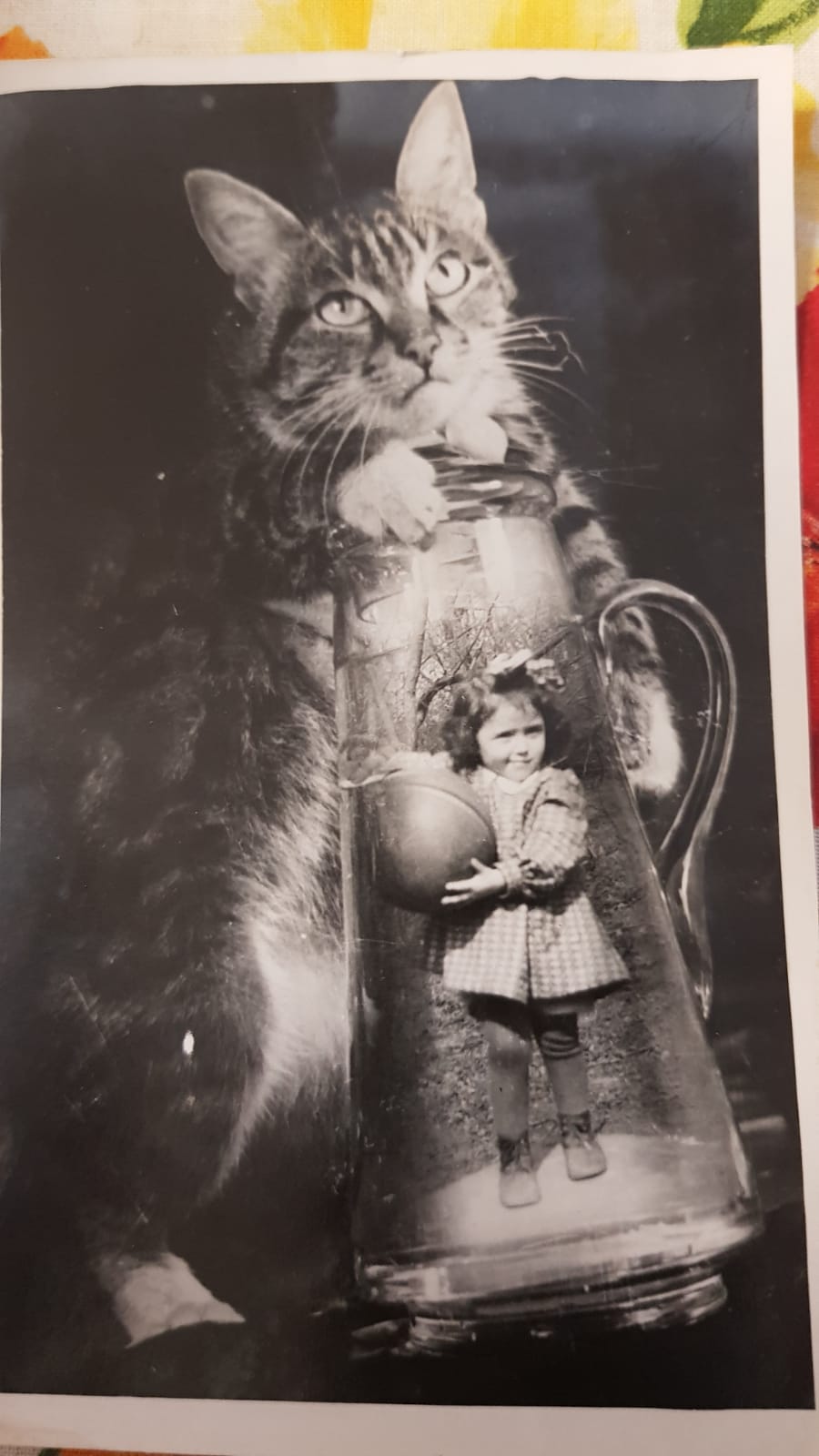

Batya also has an unforgettable memory: "One day, Dad showed me a photo he took that showed a man apparently sitting inside a bottle. I was so excited about it and asked Dad to show me the picture repeatedly. Finally, he told me, 'If you want so much – I'll photograph you in a bottle, too.' I remember thinking and wondering – how will Dad get me in the bottle? Maybe he would take a fork and push? It might hurt a bit, but Dad certainly wouldn't hurt me too much... And what if he forgets to get me out of the bottle? I remember it preoccupied me so much. Those were beautiful, innocent days. No one could have imagined that something so cruel would cut short this good routine."

Artistic photos. Example inside a kettle

Artistic photos. Example inside a kettle

Trying to Create Routine

Batya returns to the terrible days of the war: "After we moved to the ghetto, we all engaged in forced labor; Mom stood me on a brick and put lipstick on my lips so I'd appear older than my real age, so they made me, a nine-year-old girl, engage in sewing. Every day I went to work with all the adults. I felt like a dwarf, and Mom repeatedly said, 'Even if we survive, Batya will be a dwarf.' For three years, I didn't grow, wore the same dress, the same coat, and the same shoes. Surprisingly, after the war, there was a change; once freed and I started eating, I gained weight immediately. My sister was hospitalized with typhus in those days, and when she was released, she didn't recognize me and asked, 'Who is this girl?'"

When Batya speaks of her family, her voice shakes. "The unthinkable happened to us; out of the entire ghetto where thousands of Jews were, only 500 people survived after the war, and from the town of Yanova, about 100. Our family, to the best of my knowledge, was the only one that survived intact – Dad, Mom, and four children. It was a miracle from Heaven; we felt Hashem wanted to keep us. There's no other explanation."

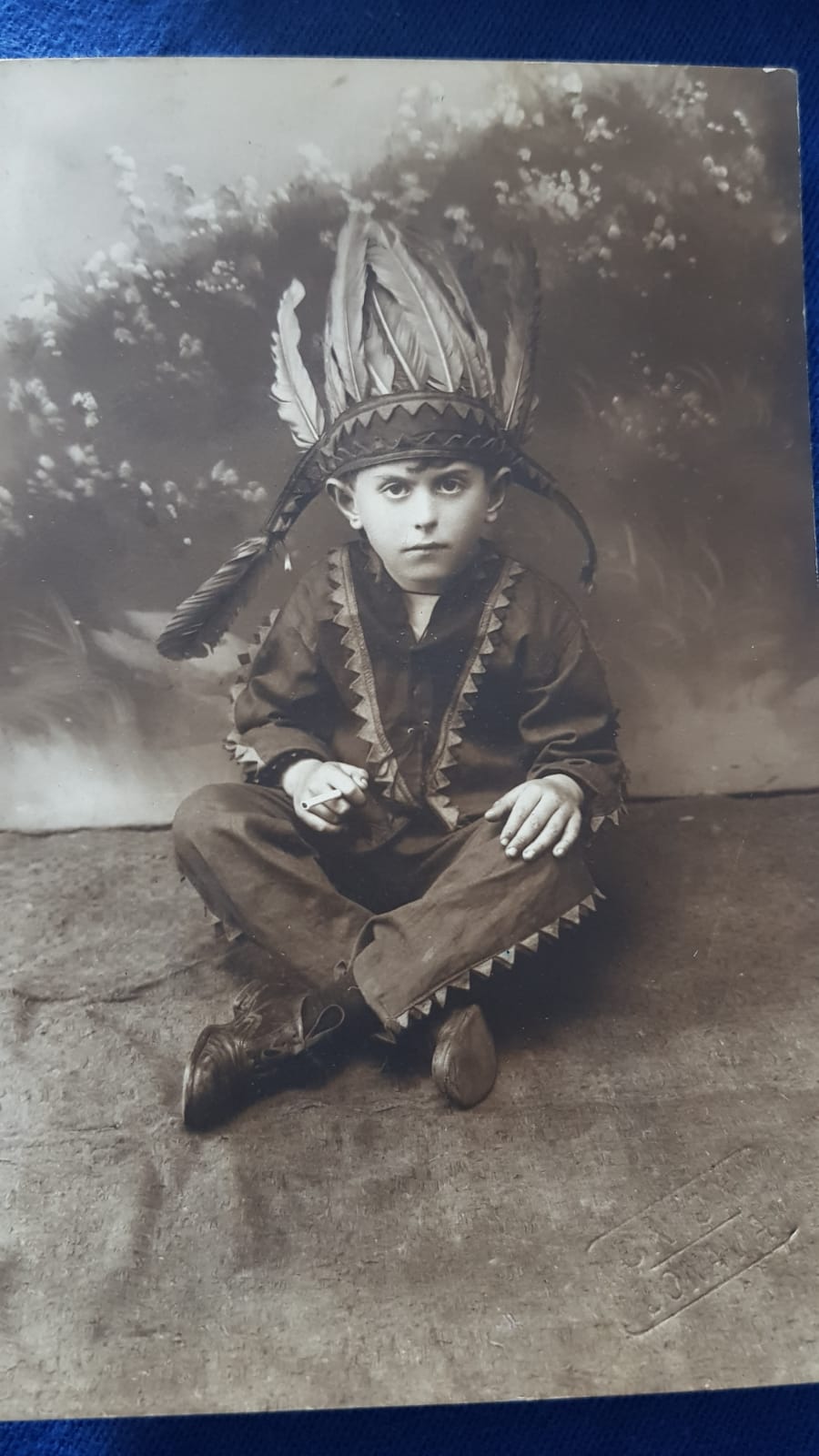

This is writer Kanovich as a child

This is writer Kanovich as a childAfter liberation from the ghetto, the Joffe family didn't return home, as there was nowhere to return to. "All the houses in Yanova burned down, nothing remained," Batya clarifies, "So we stayed in Kovno and rented a flat, or more accurately – two tiny rooms. We needed nothing more. We had no clothes or belongings to store."

Although the ghetto was liberated, the war had not ended. "Nevertheless, my parents were keen to create some sort of routine," Batya points out, "One thing they insisted on was sending us to school. I remember going to study and discovering that all students from grades one to eight were divided into two classes because the surviving children ranged widely in age. We studied in Yiddish and mainly learned about Eretz Yisrael and the Torah. A year later, I was put into a Russian school, even though I didn't know a single word of Russian because we only spoke Yiddish at home. I skipped many grades, placed straight into fifth grade."

Batya smiles but doesn't let the smile linger long, as the memories are indelible. "We did experience an unfathomable miracle, with our entire family surviving, but one cannot ignore that there were also people very close to us who were killed in the war. Almost all of Mom's family was killed, including Grandma, and the same on Dad's side. We had hardly any relatives left, but we fought with all our might to keep living."

As part of trying to return to routine, Batya's father decided to return to his work as a photographer. "Dad set up a new studio and gave it the name of the old one, 'Union,'" she says. "The new studio Dad opened wasn't as large and spacious as the previous one, but he rented a flat with several rooms and invited people for photographs. This time, different people came compared to those before the war, most not even Jewish, but Russians wanting to send pictures to family. Because the town we lived in was very close to Kovno, many soldiers passed through and stopped to be photographed. Suddenly, pictures had newfound value as they documented those who survived, those who were living."

"But the main difference in pre-war photos to those after was the clothing of people. Before the war, people came to be photographed in their best outfits, and after the war, no one had anything; everyone was photographed in their regular clothes. But Dad continued to be charming and charismatic, creating a good atmosphere and trying, even in such a sensitive situation, when people carried much pain and sorrow, to spread joy and humor."

Exile in Siberia

The Joffe family hoped to settle and forget the hardships, but the routine didn't last. One night, they received the news that the entire family was being exiled to Siberia. "Our only guilt was that Dad was wealthy before the war," Batya laments, "Of course, we tried to argue, but it didn't help. So, we were sent to Siberia and stayed there for 25 years. We studied, married, and even had children there until we learned in the early '70s that there was a chance to move to the Land of Israel, fulfilling the dream that had always accompanied us. When we understood this, we moved back to Lithuania for two years, considered 'refuseniks.' Only after enormous efforts did we receive the permits and could finally move to Israel."

In 1975, Batya emigrated to Israel with her husband and two children; the rest joined later. "Sadly, our father, who always said 'Next year in the rebuilt Jerusalem,' passed away in Siberia, and my older sister also died there after trying to reach Israel in 1946, only to be caught at the border and jailed. She's buried next to my father. But her children did what their mother didn't live to do – one daughter now lives in Israel, and the other is in the process of emigrating. Now, the entire extended family resides in Israel; we meet often and maintain very warm connections."

Batya notes that for many years, she and her siblings mourned that there was no trace left of all the photos their father took before the war, as the pictures in Yanova were destroyed when the entire town went up in flames, and those from Kovno were left behind when they were taken to Siberia.

"After many years, when we were already living in Israel, we were contacted by my father's cousin, who lived in the U.S.," Batya surprises, "He was already 80 years old but mentioned that Dad used to send him our photos before the war, and now he had the opportunity to return them to us."

Batya mentions that the moment of receiving the photos was incredibly emotional. "It's not just receiving a memento; it's much more than that – these are photos that are part of our lives. After all, Dad took them, and his whole life revolved around photos. We managed to gather quite a few pictures in our hands, some of us and some featuring other people that Dad photographed."

An Exhibition for Generations

But the Joffe family story has a surprisingly incredible continuation. At this point, Len, Batya's daughter, joins the conversation and shares a remarkable event: "A few years ago, we traveled with our parents on a roots journey to Lithuania and visited, among others, our cousin who lived there. The cousin connected us with a historian named Arthuras Narkevichus from Yanova, who was surprised to learn that mom is Tuvia Joffe's daughter and we are his grandchildren. He told us he was collecting photos from the studio, as they document the town that was obliterated. The historian showed us all the photos he gathered, and also the things he wrote about Grandpa. We completed what was missing and added our photos to the collection. We ended up with just under 200 photos, providing the main basis for an exhibition that debuted a few years ago in three different cities in Lithuania."

Len, Batya's daughter

Len, Batya's daughterLen notes that at the exhibition, you can see, for example, a photo of the Jewish writer Grigory Kanovich, who passed away just last month, a Purim photo of a child who came to be photographed, and many more pictures of people, women and children, who unfortunately did not survive the war.

Purim photo of a child who came to be photographed

Purim photo of a child who came to be photographed"In the coming days, the exhibition is about to be displayed for the first time in Israel, initially at 'Tzohar' in Lod, and after a few weeks, it will move to 'Tzohar for Roots' in Jerusalem, and we plan to present it in many other places around the country," explains Len.

"It particularly excites us that the exhibition is opening at this time," comments Batya, "because this week marks Dad's birthday – Tuvia Joffe, the unique figure behind those photos. We feel the exhibition has such a strong message of Judaism and values reinforcement. Yes, we also have hope that following the exhibition, other families will see the photos and maybe even recognize their loved ones. From our experience, every photo has unimaginable value, and each is worthy of finding its way to family members."