Righteous Among the Nations: "I Didn't Ask If I Should Do It, I Asked How"

Irena Gut was 17 when Poland fell to the Nazi regime. She courageously smuggled Jews out from under the nose of the German army officer she served. We spoke with Yael Shalmon-Barnea, who translated Irena's story into Hebrew, on the eve of the Tenth of Tevet.

(In the circle: Irena, 17, nursing student, 1939, Radom)

(In the circle: Irena, 17, nursing student, 1939, Radom)How are heroes born? It turns out that the first steps are always small. When Irena Gut, a Righteous Among the Nations, describes in her book 'In My Hands' what she went through during World War II, she emphasizes that she wasn't born a heroine, and when the bombs whistled over Poland, she was definitely scared. But as evidenced by her story, which has become a worldwide bestseller and recently translated into Hebrew, even a young seventeen-year-old girl had a role to play in the face of the Nazi monster that conquered her homeland.

When Irena outlines the creative and daring ways she risked her life personally to save Jews she didn't know, she repeatedly emphasizes, "I didn't ask myself if I should do this, I asked myself, 'How do I do this?'"

Irena can no longer be interviewed about her life story, as she passed away in 2003, shortly after being recognized by Yad Vashem as a Righteous Among the Nations. However, one can certainly converse with Yael Shalmon-Barnea, the translator of the Hebrew edition, and hear from her about the fascinating translation task and the incredible story of a 17-year-old girl during the harsh wartime.

Yael Shalmon Barnea, the translator of the book into Hebrew

Yael Shalmon Barnea, the translator of the book into Hebrew"I Couldn't Do Nothing"

"The book was written in English by Jennifer Armstrong, and I translated it," Yael emphasizes at the start of the conversation. "I first read it over a decade ago when my aunt in New York recommended it to me, and I immediately thought it must be available in Hebrew. In practice, things were delayed until I undertook the task about three years ago. I worked on the translation for about two years, then delayed it for another year due to COVID and other constraints, until it was finally published recently."

Irena's story is almost unimaginable. "It seems that from a young age she wanted to be a 'good person'," says Yael. "That's how she entered nursing studies, and when the war broke out, instead of returning to her parents' home, she found herself moving with the Polish army towards the Soviet Union. She went through several transformations, journeys, and hardships until she eventually started serving in the Nazi officers' kitchen in Tarnopol."

Yael continues, saying that as a kitchen worker in a building turned Nazi hotel, Irena repeatedly heard senior officers discussing the "Jewish problem", but she still didn't understand the magnitude of the tragedy. Only one day, when sent to set tables upstairs, did she see from one of the top windows what was happening in the ghetto. "Suddenly gunfire broke into the quiet ballroom," Irena describes in the book. "I ran to the window to see what was happening. The scene below was like an anthill being trampled – men, women, and children ran in the streets, SS men poured out of the trucks and shot at the fleeing Jews. The white snow turned red with blood. It was unreal. It couldn't be real." Irena goes on to describe how, until that point, she had seen the cruelty and brutality towards the Polish people but hadn't imagined how much worse the Jews had it.

"In the afternoon, when I cleaned up after the meal, I found myself alone in the kitchen," Irena continues. "I had been waiting for this opportunity. I took a trash bucket from the floor beside me and went toward the ghetto. Taking a quick glance at the street, I approached the fence, took a large cooking spoon, knelt down, and scraped at the dirt until I made a small hole under the fence, about the size of a loaf of bread. From the bucket, I took a layer of potato peels and a tin can filled with cheese and apples, pushed it through the hole, and hurried back to the kitchen. 'Helping a Jew – punishment is death,' was the warning I heard repeatedly. It was written on posters and announced over loudspeakers in the city's streets. Despite this, every day I found a chance to slip out and leave food under the fence. I knew it was a drop in the ocean, but I couldn't do nothing."

In the Nazi Commander's Basement

The most remarkable aspect of Irena's story is the fact that she attempts in every way to help Jews even when appointed as an aide to a German army commander, managing to rescue Jews from the inferno right under the noses of the commanders from the SS.

Further into the book, she describes how she utilized her position near the top Nazi officials responsible for the entire area – the army commander and the SS commander. Many times they would sit together to eat, and Irena would serve them food, hearing everything they said. Whenever she overheard plans for an impending action, she would ride her bike to the ghetto and announce to the Jews: "Run, it’s coming!" At odd hours, she would sneak Jews into the nearby forest, using a cart she rented for them. On their way to the forest, they had to pass inspections and checkpoints, repeatedly risking her life.

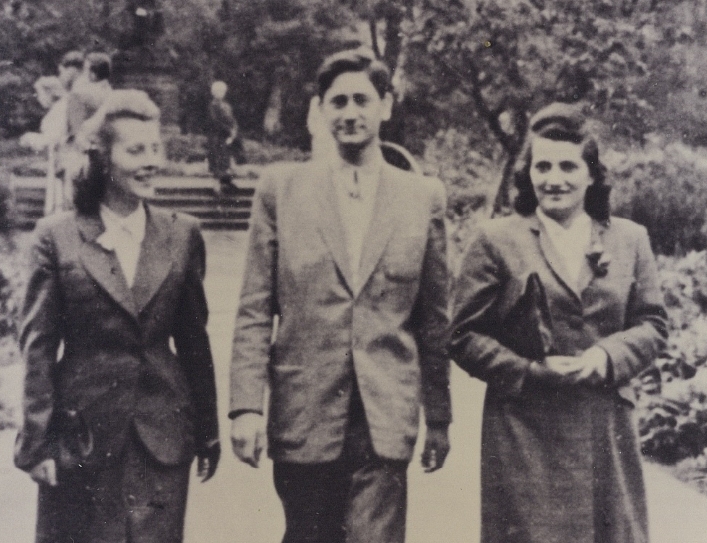

1945, Krakow. Irene, Hershl, and Paula Morris. Irene in the suit tailored by Hershl (Credit: Courtesy of the family)

1945, Krakow. Irene, Hershl, and Paula Morris. Irene in the suit tailored by Hershl (Credit: Courtesy of the family)Besides working in the officers' kitchen, Irena was also in charge of the laundry, employing Jews there. Even in this role, she mobilized for their sake, and even on the last night when she knew the Nazis' plan – that the next day there would be no more Jews in Tarnopol, she told them: "You're not returning to the ghetto tomorrow but staying here." Then she performed the most daring and inconceivable act imaginable – she moved them into the Nazi officer’s house, smuggled them into his basement, where they hid until the war's end.

Twelve people hid in the basement, and during their stay, it was discovered that one of the women was pregnant. Irena describes debating whether to bring tools to perform an abortion, given the significant risk that a crying baby would reveal their hiding place. She also mentions that she couldn't bring herself to do it, and eventually, the infant survived alongside the others in the basement.

Towards the end of the book, there is a sense of closure, as after the war ends, Jews whom Irena saved end up saving her. Yael excitedly quotes Irena’s conversation with her Jewish saviors:

"Hashem blessed you with a family. Now help me find mine," I pleaded. "They lived in Kozlowa Góra, in Upper Silesia. Could you help me? I can't move freely with the Russians–"

"Whatever you need, Irena. We'll find them," Ida kissed me again, then Phoenix carried me back upstairs, through the door, to the backseat of the car, and covered me with a blanket."

For two weeks, Moishe Lifshitz and his wife Paula cared for me until I recovered. They told me they had been in the Tarnopol ghetto and escaped thanks to one of my early warnings. Now they were eager to repay me. Rumor from Katowice was that I'm a dangerous criminal, wanted by the Soviets, and they were trying to hunt me down in the area."

Simply Saying Thanks

Yael has been involved in translation and editing for years, but translating this book wasn't easy for her at all. "Overall, it's a painful story about a horrific period with the greatest human atrocities," she explains. "During the translation, whenever I went through the words, I cried in the same places repeatedly, sometimes even before that, because as a translator, I knew what was coming. It drained me emotionally."

The front cover (Credit: Ilona Bezauszko | Psycat Covers)

The front cover (Credit: Ilona Bezauszko | Psycat Covers)There are so many unpublished stories about Jews who survived the Holocaust. Why do you think it's important to memorialize the Holocaust through the eyes of someone who isn't Jewish?

"I think there's a lot of hope seeing that there are good people from all religions," Yael believes. "Personally, I was so moved to read on the 'Yad Vashem' site about all the Muslim Righteous Among the Nations. It was really important for me so that we don’t create a Holocaust out of ignorance, and mainly so that we know to preserve human dignity if found in a position to help. Both survivors' stories and those of the Righteous Among the Nations are important for a more comprehensive picture of the human spirit's power. To show us these things are possible and miracles can happen."

Do you think Irena was so exceptional, or are there others like her whose stories we just don’t know?

"Can I say both? There's no doubt Irena was very special. I believe all readers can fall in love with her, and it happened to me too. But are there more similar stories? Of that, I have no doubt, but it's clear to me we lack testimonies for all of them. Acquiring such a testimony isn't easy at all. The people who helped during the Holocaust didn’t do it for recognition, reward, or honor. They truly did what they felt they should do at that moment, and no one really knows where they found the courage and strength to do it. Irena never sought posthumous recognition, and more so – she began sharing her story because she began hearing about Holocaust deniers appearing worldwide. She couldn't tolerate it, so she started speaking in schools, synagogues, to both Gentiles and Jews, to tell her story and recount events."

Irena (first from the right) at the nursing school (Credit: Courtesy of the family)

Irena (first from the right) at the nursing school (Credit: Courtesy of the family)If you were to meet Irena, what would you say to her?

"I couldn't meet Irena since she passed away before I read the book. Initially, understanding she's no longer alive, I felt a kind of loss because I had so much to say to her and so many things to ask, but the truth is if I had met Irena, I think I'd just hug her. She is, in my eyes, such an inspiring figure; I wish I could just say thank you."