"The Investigators Said: 'Convert to Islam or We Will Kill You'"

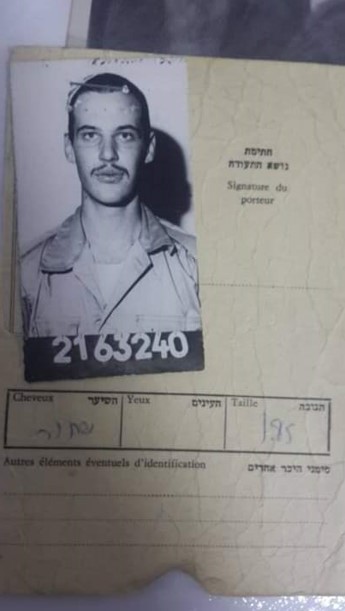

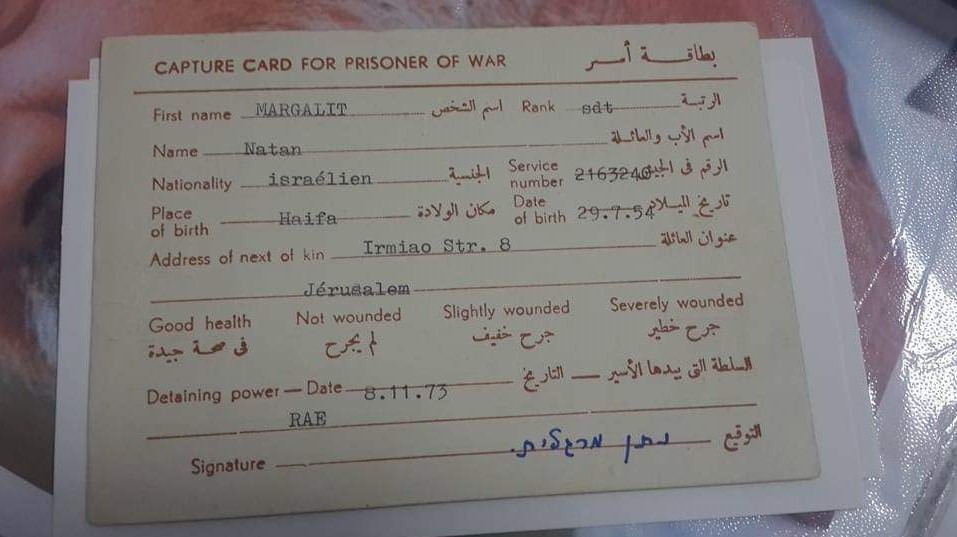

The moments when he realized that war is more than child's play, the attack on the tank that led to surrender, the long days without food in Egyptian captivity, and the moments he was taken to a synagogue in Cairo for propaganda purposes. After years of memories, with the world tense about a new conflict, Natan Margalit shares his recollections of the Yom Kippur War.

In these days, when the winds of war are blowing, and the entire world is closely watching the situation on the Russia-Ukraine border, there are those who see these events and are reminded of their personal war experiences.

This is Natan Margalit, currently a retiree of Clalit Health Services, and formerly a young soldier who served in one of the northern outposts on the Suez Canal during the Yom Kippur War. When he recalls the events that took place during that difficult war, you can't help but hear the tremor in his voice, the terror in his throat, and understand that war is no joke. It's something that leaves a mark, following the warriors for the rest of their lives.

Alone in the Outpost

"I was just a 19-year-old at the time," he goes back to those days. "You have to understand that the atmosphere back then was completely different from today. It was shortly after the Six-Day War, and everyone was drunk with euphoria, having conquered three countries in just six days. The feeling of 'our own strength and power' was immense, and people felt that there were no limits to the IDF's capabilities. Personally, I had the chance to be exposed to contingency plans stating who would be the city officer in Antalya, Turkey, as well as to maps and military stretches of additional areas we intended to conquer and control. It was as if we were a massive empire.

"Probably due to this immense euphoria, someone fell asleep on the job and didn't read the map correctly. The awakening was too late and came at a heavy price."

Margalit tells about himself: "I was then at the Suez Canal, and we were just engaged in routine drills. Yet, that morning of Yom Kippur, we were informed that at six in the evening gunfire was expected, and therefore we should pack up our external observation posts by 4 PM and return to the outpost. We still didn't realize it was war until 1:30 PM, when an urgent update was received – 'What is expected at six in the evening will break out within a few minutes.' A few moments later, an Egyptian plane was flying over the canal, signaling the start of the artillery assault. That was essentially how the war began, while we were fasting, inside the canal."

Did you feel fear?

"At this stage, we weren't afraid, we didn't even understand what was happening, but we felt entirely in the battlefield, hiding inside the bunker that shook with every shell and shell."

Margalit notes that there is an organized procedure for leaving the bunker, which states that you have to wait until the artillery stops and then leave in pairs, certainly not all together. "Once we got out, the situation became dire – we suddenly realized that war is no joke, it's not just smell and gunpowder. Suddenly we saw our medic killed and another person lifeless. I remember climbing into the position and being hit by a rain of shells. It was an especially furious attack that came as a complete surprise."

In the next stage, Egypt began to attack from three directions, and it became serious moment by moment. "At one point when I was standing outside, I suddenly saw a tank directly in front of me. I tried to fire at it, and then I saw a giant flame coming out of it and hitting my position – all the sandbags collapsed and nearly buried me. I was hit by shrapnel, mainly around the head, the position was completely destroyed, and at the last moment, I managed to squeeze into the bunker to rinse my face and check my condition."

The attack continued all night, and by morning, Margalit and his friends already understood that they had run out of ammunition, and of course, they couldn't fight with stones and sticks, which meant they had to retreat. In the afternoon hours, they received an organized retreat order that allowed them to leave the outpost and retreat back into Sinai. The plan was to continue, of course, into Israeli territory, but along the way, Egyptian army ambushes appeared.

"Initially, we managed to pass several ambushes peacefully," Margalit details, "but then the Egyptians spotted us, and they placed mines on the road, didn't even bother to bury them in the sand – our first tank passed between the mines, the second tank tried to pass but hit a mine, while we were in the third vehicle and didn't even have time to try, as we were hit in the front part of the vehicle. We had no choice but to flee the vehicle, with the Egyptians surrounding us and capturing whoever managed to survive."

"We were a company of 48 soldiers," Margalit states the difficult numbers, "and from those, only 18 returned, each with their own difficult story – some of us were wounded, some captured, and there were those who were both injured and captured. Only one soldier managed to escape unharmed."

"Put Your Hand and Convert to Islam"

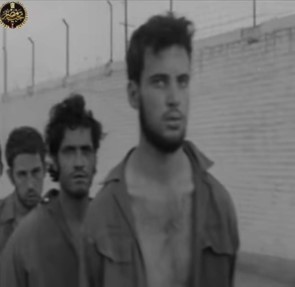

Natan Margalit himself was captured, and he notes that the hours when they were led on the banks of the canal, to Cairo, were the hardest of his life. Throughout the journey, they were ordered to shout: "Long live Sadat, Dayan is dead, Golda is dead." "Their goal was to trample on the heroes of Israel of that era," he explains, "It was very humiliating."

He was in Egyptian captivity for three months, and according to him, the most difficult thing was the loneliness. "Although there were many soldiers who were captured, each of us was in a separate cell and couldn't keep in touch. Being in the company of fleas for three months is one of the most difficult things."

What went through your mind during all those days? What were your thoughts occupied with?

"On one hand, the Egyptians kept proudly telling us that they had conquered Be'er Sheva and Tel Aviv, that all of Israel would soon be in their hands. I didn't believe them, I was sure it was an overactive Arab imagination, but when they moved me occasionally from place to place and I saw massive amounts of prisoners on the way, I began to believe that their achievements might be bigger than I thought."

Tell about the interrogations. What were you asked during them?

"In the first interrogation they wanted mainly personal details – first and last name, service number, then they asked me: 'Which corps do you belong to?' I wanted to tell the truth – 'Infantry', but at the last moment I realized it would be a mistake to say that, so I changed it and said: 'Rabbinate Corps'. The investigators were angry: 'There is no such corps.' I insisted there is, and in return, they pulled out a huge book on the Israeli army, listing all the most classified units, which I myself didn't know about, proving to me that there is no such thing as a Rabbinate Corps. But I continued to insist, and since I was among the few soldiers with a kippah, it apparently made sense to them. From then on, they treated me as a religious figure."

"One day, they devised a horrifying tactic – the investigators took me out of the cell in the middle of the night, into the yard, then suddenly I saw a dim light, and a table with a green cloth on it came into view, with a book that looked like a holy book, with golden, ornamental letters. The investigator told me: 'Put your hand on the book,' and I immediately understood it was a Quran. He continued to demand: 'Now say everything I say to you,' and continued: 'We've decided to convert you to Islam.'

"I don't know where my courage came from, as a 19-year-old, to burst out and ask him: 'You have 20 million Muslims, why do you need another one?' And he answered me seriously: 'You're not just another one, you're a religious figure, and we want you to be a Muslim.' I told them I certainly wasn't willing, and their response was: 'We will execute you tomorrow at the sixth hour.' Afterward, they blindfolded me and returned me to the cell. The night that followed was horrifying, with thoughts constantly trying to comprehend what the sixth hour was and in what way they were planning the execution. I didn't have a watch, so I couldn't estimate the times precisely, but I concluded that if I see the location of the shadow through the window, it means the day is already over, and if so – probably they won't kill me, and they just wanted to scare and threaten. Ultimately, as you can comprehend, if I am chatting with you today, then most likely the plan was canceled.

"By the way," he adds, "I later found out that it wasn't just me who went through this unpleasant experience, since the Egyptians tried to convert even non-religious guys, some of whom were really secular. I had the chance to talk with someone like that, and I asked him: 'I understand why I, a religious guy, wouldn't convert to Islam, but you eat meat and milk on Yom Kippur, why didn't you convert? They could have killed you.' His answer gave me a glimpse of what the nation of Israel is about. He said: 'You exaggerate! There are things I'm not ready to do by any means, I'm ready to die rather than do them.'"

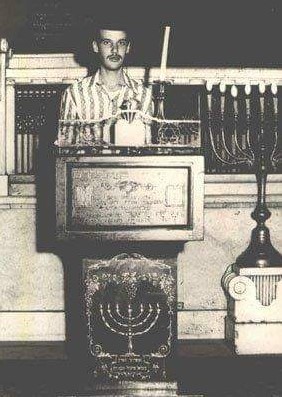

The visit to Sha'ar Hashamaim Synagogue in Cairo

The visit to Sha'ar Hashamaim Synagogue in CairoHungry for Bread

What about food? Did they give you food during that time?

"In the first month, we hardly received any food, because it was the month of Ramadan, and the Egyptians felt it was impossible for them to fast whereas their captives would be eating. In fact, only during Sukkot – four days after Yom Kippur, the day I was captured, I received my first meal – pita with salt, raw potato, and onion. At first, I shook off the salt and swallowed the pita, then asked myself what to do with a raw potato, but out of extreme hunger, I ate it as well, and I even finished the onion. This was the meal that broke the Yom Kippur fast for me. Later, when Ramadan ended, they brought us slightly more food. Meals mainly consisted of fava beans and were very modest and unsatisfying. I lost 17 kilograms during that period, and I'm not the only one – after captivity, we all looked like skeletal figures."

He also has an unforgettable memory: "On the last Shabbat of our imprisonment, I was surprisingly taken out of the cell and asked a question that had never been asked before: 'What is your shirt, pants, and shoe size?' After I answered, they brought me civilian clothes and ordered me to quickly change and go outside. Outside, I discovered two other religious soldiers I'd known, who were captured. The three of us were put into a vehicle and driven without any explanation of our destination. Only when the vehicle stopped did we find out we had arrived at a synagogue in Cairo, where they took us outside and demanded we enter. The worshippers were in the middle of kedushah, so we stood still and didn't move forward. The Egyptian rebuked us, not understanding that in kedushah, one should stand without moving.

"What later became clear is that they brought us there for propaganda purposes, demanding we tell everyone how good our lives were in Egyptian prison. We had no choice and provided what they wanted. There were television crews there recording us and broadcasting it to the world. Afterward, they returned us to our cells, we changed back into captivity clothes, and resumed wearing the prisoner uniforms."

A few days later, the release came. "We were unexpectedly taken out of the cells, without our hands or eyes bound, and led into a large hall, where we finally met all our friends again for the first time in three months.

"Then the Egyptian Minister of War entered and gave a speech in which he explained that Egypt had engaged in an entirely defensive war, explaining how Egypt was protecting its citizens at the line of fire. It was a bunch of lies, and finally, he announced that the war was over, a ceasefire was declared, and as part of it, a prisoner exchange deal was made. That's when we realized we were actually being released."

The next day, Margalit was on a flight to the country, from which he mainly recalls the following story: "There was an older reservist who told me: 'Go into the plane's bathroom, there's an experience waiting for you.' I went to the bathroom as he suggested, washed my hands, and suddenly I saw someone on the other side washing their hands too. It was my reflection in the mirror, but I didn't recognize myself. I had lost weight, grown a beard, and looked horrendous. It took me a while to realize it was actually me. It was a truly shaking experience."

Faithful and Grateful

Today, so many years after the war, what mainly stays with you?

"To this day, I have great disappointment with the entire political leadership, which didn't truly know how to welcome us back as captives. There was a significant lack of experience in the matter, and every request I needed or recognition I sought, I had to plea and request, and even then not always receiving it. I never understood the logic behind it – after all, I wasn't taken captive and beaten because my name is Natan Margalit, but because I wore the IDF uniform, so why isn't there anyone standing behind me?

"And there is something else I've learned over the years – captivity isn't something that starts and ends, but it revolves around one's whole life. Even now, decades after the war, not a day goes by without nightmares. I have a severe sensitivity to noise, and when I am at an event, I always leave very quickly, unable to continue staying there; I find it difficult even to sit in a restaurant, and when I am there, I sit only with my back to the wall, so no one surprises me. I am well aware that these things are due to captivity. Simultaneously, I must note that captivity gave me great strength, and also a lot of closeness and faith. Today I am a much more believing person, and I also know how to be grateful for all the abundance I have had during my life. It is clear to me that nothing is taken for granted."