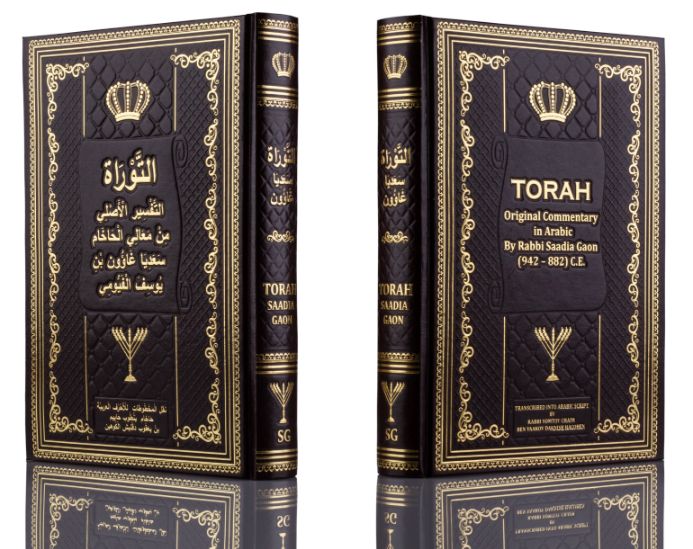

The Rabbi Translating Sacred Texts into Arabic: "This is My Life's Mission"

Rabbi Yom Tov Gindi lost his sight about 12 years ago, but this doesn't stop him from dedicating all his time to translating Rabbi Saadia Gaon's commentary into Arabic and Hebrew. "It all began in my childhood in Aleppo, Syria," he reveals.

Rabbi Yom Tov Gindi

Rabbi Yom Tov Gindi"Translating sacred texts into Arabic?" I ask Rabbi Yom Tov Gindi, sure that my ears are deceiving me. "Into Arabic?"

He smiles and confirms. "Yes," he says, "I am working on translating Rabbi Saadia Gaon's commentary on the Torah into Arabic. I have been dedicating eight years to this. It is my life's project."

And don't be mistaken. This is not easy for him at all. About 12 years ago, Rabbi Gindi lost his eyesight, and he works on the translation using special computer software, typing blindly in Hebrew, Arabic, and English, and the computer reads aloud what he has written.

"Arabic is my mother tongue," he emphasizes, "and it's also the language in which Rabbi Saadia Gaon wrote his commentary over a thousand years ago. However, Rabbi Saadia Gaon wrote Arabic using Hebrew letters, making it difficult for Arabic speakers to read the commentary. On the other hand, Hebrew speakers also struggle because they can't understand the words' meanings. I am working on translating the commentary into both Arabic and Hebrew, making it accessible to everyone."

The Journey from Aleppo to Israel

Rabbi Gindi has been connected to the Arabic language since his childhood when he grew up in Aleppo, Syria. "I was born in 1955 to a devout family," he recounts. "We lived within a large Jewish community, and as a child, I was sent to study Torah seven days a week, including on Shabbat, where we only studied sacred subjects. The atmosphere in the community was very spiritual; we adhered strictly even to minor commandments, and there was a specific emphasis on teaching children from a young age to read the Bible correctly, understanding all the nuances."

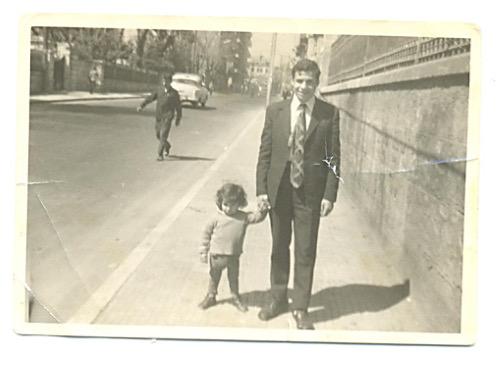

His father and younger brother on a street in Aleppo

His father and younger brother on a street in AleppoDid you experience antisemitism?

"Yes, unfortunately, there were many Arab residents in Aleppo who tried to harass community members, especially children. I remember one day during the Six-Day War, I returned home from Torah studies, and one of the workers from the laundry called me over and said, 'Wait and see, we will slaughter you soon.' At that time, all Aleppo residents were sure that the State of Israel was about to collapse. Some of the workers employed by my father went through our apartments and marked what each would take as loot and who would inherit the house. After a week when the war ended in a surprising victory for the Jews, the Arabs approached us with bowed heads, saying, 'We were good neighbors, remember? So when Israelis come here, tell them about it...'"

Rabbi Gindi notes that these "good neighbors" also ensured that from 1990 to 1994, no Jew could leave Syria, and before that—in the 1980s—only one family member could leave for medical treatment exclusively. They ensured that Jewish families could not escape Syria.

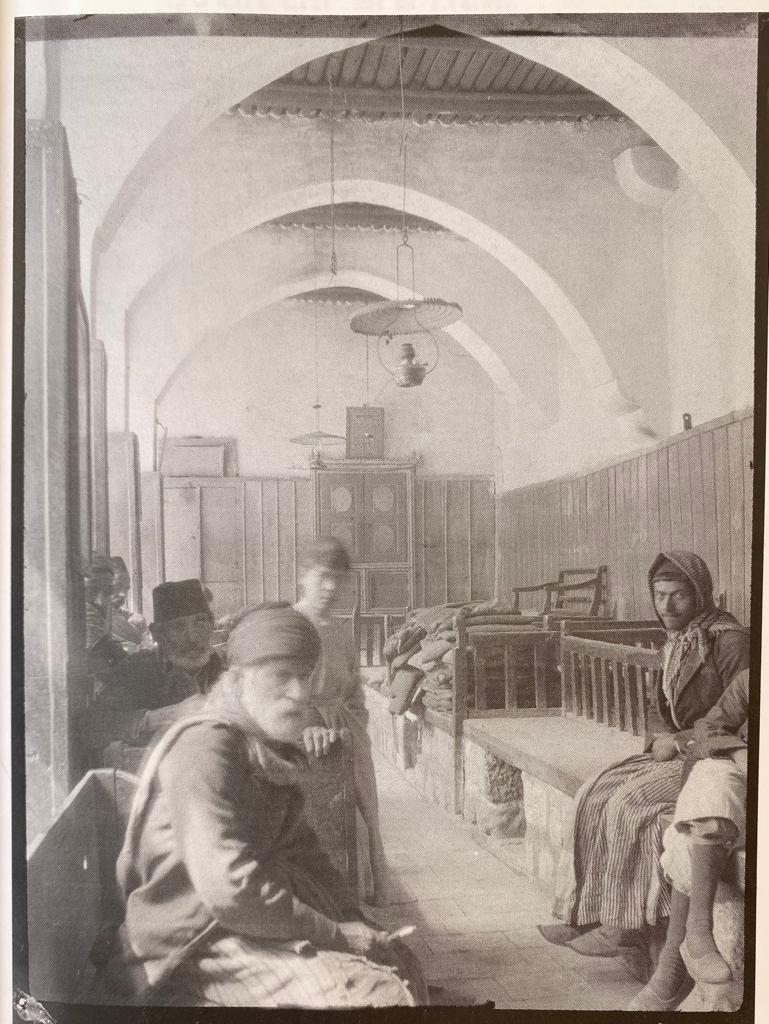

The Great Synagogue of Aleppo

The Great Synagogue of Aleppo"I remember in 1990 when the Iron Curtain fell, the Lubavitcher Rebbe said that just as the gates were opened for Russian Jews, so too would they open for Syrian Jews. Indeed, by 1992, it was possible for any Jew wishing to leave Syria to go to America, so the Jewish community almost completely emptied."

But he himself immigrated to Israel much earlier. "When I was 17, a traumatic murder occurred in Aleppo—a non-Jew bet with his friends that he could kill Jews, and indeed he murdered a young Jewish man named Zaki Katzav. During the murder in 1973, the entire Jewish community was in turmoil. We young people took the bloodstained coffin with the stained shirt on top and marched in a procession along 500 meters to a street with embassies, where they forcibly returned us and dispersed the funeral. Already then, I felt I couldn't stay in Aleppo even if they wouldn't allow me to participate in the funeral as I wanted. It was clear to me that my future was not there."

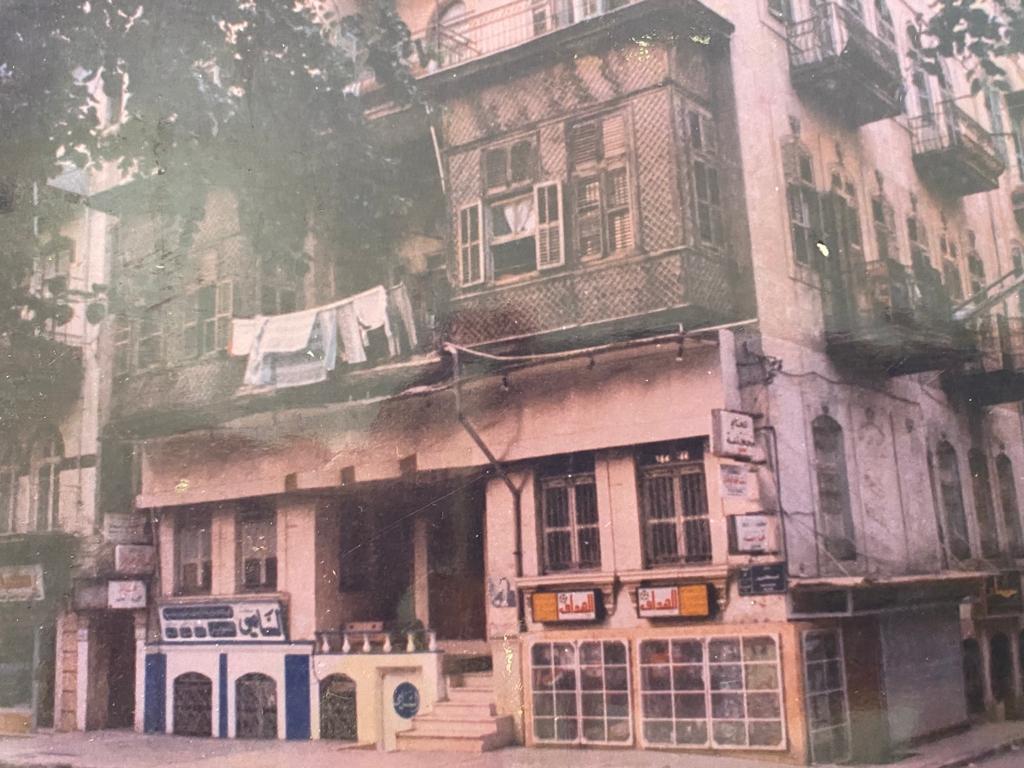

Family building of my father

Family building of my father"By the grace of Hashem, shortly afterward, I escaped to Israel through the border," he recounts. "I did it with the help of a smuggler, who, of course, demanded a lot of money for it. Along with me were my two sisters, and we arrived in the country, leaving our parents behind with younger siblings. One of my brothers also managed to immigrate to Israel shortly after us. In fact, I did not meet my parents for nearly ten years, and during that entire period, I had to take care of my sisters—support all three of us and provide shelter and food. Alongside all this, I studied electrical engineering and served as an officer in the Air Force."

During those days, Rabbi Gindi connected with the Chabad Hasidic movement after attending a Chanukah party for students studying with him at the university. "I attended the event, and it moved me deeply—the dances and the songs suddenly reminded me of the sacred atmosphere I knew as a child. Thus, I found myself getting closer to Chassidut and later also moving to live with my sisters in Kfar Chabad."

My father as an Air Force soldier at the immigrant center in Kfar Chabad

My father as an Air Force soldier at the immigrant center in Kfar ChabadAbout ten years later, when his parents immigrated to the country, Rabbi Gindi made sure they were accommodated in the immigrant center in Kfar Chabad. By the way, Rabbi Gindi recounts that his parents and brothers escaped from Aleppo through great personal risk via Turkey, and it was a great miracle that none of the family were captured along the way. "Here in the country, it wasn't easy for them; they had to adjust to the new life and the different mentality, but they were so happy to have reached the Holy Land. That was what mattered to them. Nothing else concerned them."

Life's Project

For years, Rabbi Gindi worked in the aerospace industry, but due to a work accident that injured his eyes, his vision began to deteriorate gradually until about 12 years ago when he lost it completely. During those days, he realized he couldn't continue his job, but it was precisely the time to fulfill the dream that had accompanied him for years—to translate Rabbi Saadia Gaon's writings on the entire Bible. Thus, 'Project Saadia Gaon' was born, and he embarked on the mission.

"I believe that making the commentary accessible to Arabic speakers is an incredible opportunity for us," he says, "because essentially, there are almost no Torah commentaries translated into Arabic, unlike other languages. The few existing translations are mostly extremely distorted. For years, non-Jews who wanted to read the Bible used distorted writings, where translation was done upon translation, each altering as they wished. Now, this is an opportunity to give them a true and accurate translation."

Do you really think the translation of holy books interests them?

"It's not just that I think, I see the inquiries that reach me every day from all over the world, and it's amazing. Moreover, there is also a significant contribution to the Jewish people because, as I mentioned, my translation is both into Arabic and Hebrew. It is unprecedented because very few Jews speak Arabic, and no one has taken on this mission until now.

"You have no idea how much Kiddush Hashem has been accomplished worldwide thanks to this translation," he adds. "Since I published the books with Rabbi Saadia Gaon's commentary, they have reached countless Arabic speakers worldwide who seek to learn Judaism, and this is an opportunity to convey the messages. Some have approached me and told me that for the first time, they understand that their claims about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are incorrect since the Torah indicates precisely where the Land of Israel is, and according to Rabbi Saadia Gaon's commentary, it is not the land they claim belongs to them. Some have also told me they study the text I send them at universities and wish to translate it into additional languages. I see unequivocally how the translation I write manages to lead to much love and closeness to the Jewish people and uproot much ignorance existing worldwide."

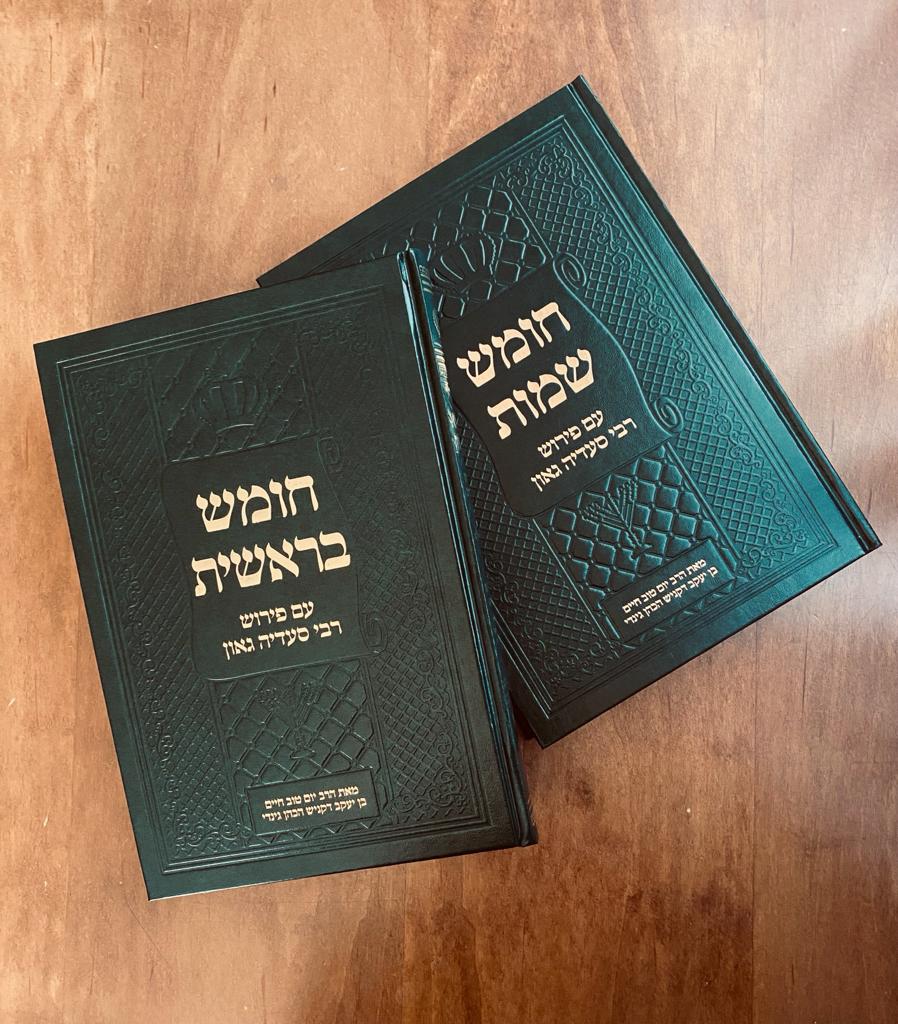

So far, Rabbi Gindi has published two books of Rabbi Saadia Gaon's commentary—on Genesis and Exodus. "These days, I am also working on the commentary on Leviticus," he says. "The work is extensive, partly because Arabic has 28 letters while Hebrew has 24. I need to be creative and manage to edit the texts accordingly. But I am working on it, and very soon, the book, with Hashem's help, will come to light."

And what are your future plans?

"I plan to continue translating the rest of RSG's works and hope this commentary will also be translated into additional languages and spread worldwide so that all creations know what true Torah is, this is my aspiration."