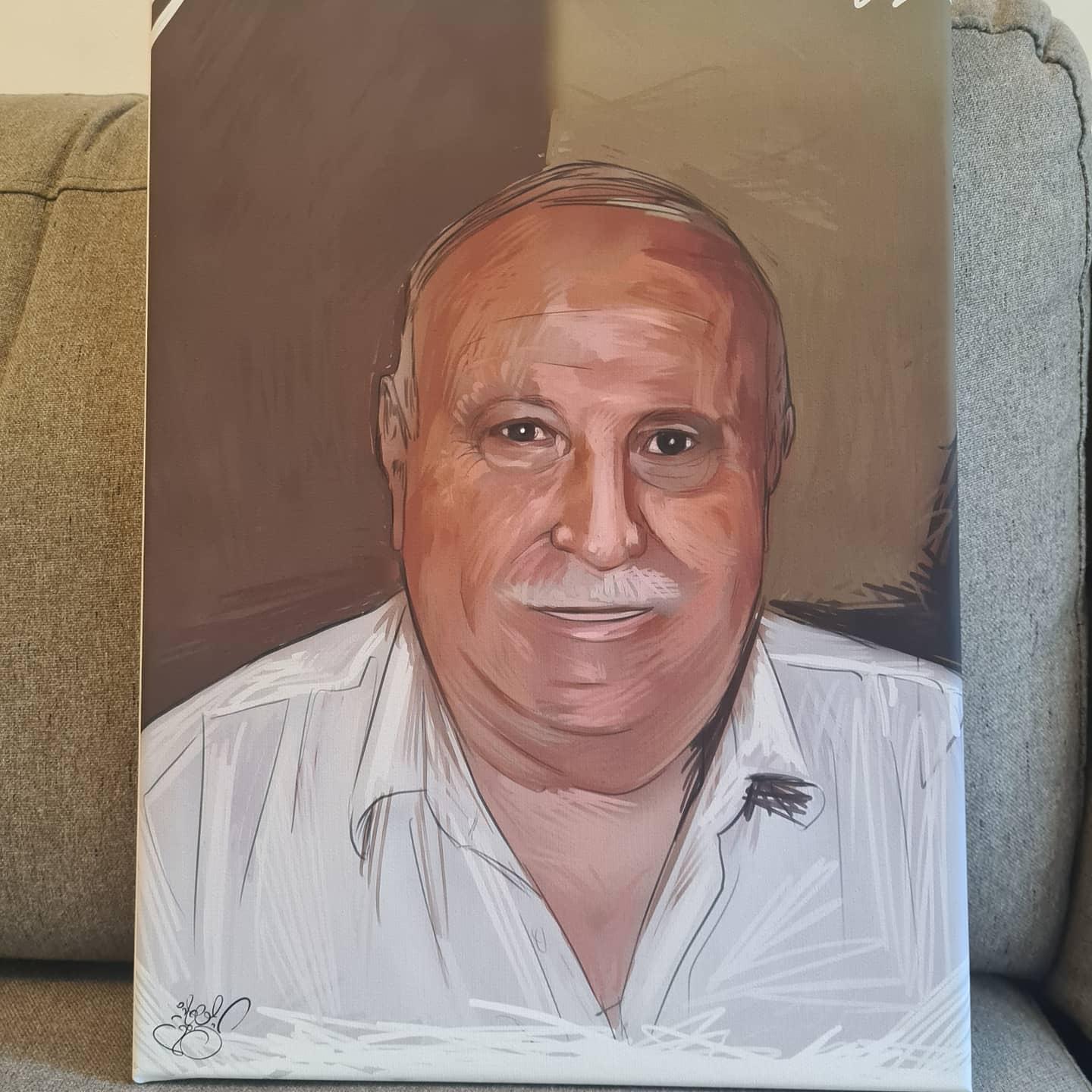

Portrait Artist Reveals: "Without Painting, I Wouldn't Have Survived Yeshiva"

Shneor Lipsker paints portraits of renowned Jewish figures, rabbis, and private individuals, having discovered his talent while facing challenges in yeshiva. What kind of 'deal' did he make with G-d?

(In the circle: Shneor Lipsker)

(In the circle: Shneor Lipsker)Many people contact artist Shneor Lipsker to commission portrait drawings. Many are surprised to hear that Lipsker, who has gained significant recognition in the past year, is a young man, only 20 years old, in his first year after marriage.

"I know it seems incredible, and even I sometimes stop and can't believe I've reached this place," he notes with a smile. "It's mainly interesting because unlike other artists who say they were 'born with a pencil in hand' or 'have been drawing since they remember themselves,' for me it was different. My first drawings were around age 12, and even then not seriously. The first time I started to realize my drawing talent was a few years later - when I began studying in yeshiva."

Lipsker pauses for a moment, takes a deep breath, and says, "When I think back on my yeshiva years, I can say they were the most amazing years of my life. I truly had the privilege to grow and to dedicate myself to learning. But as a young man, I also faced significant social challenges, and I can say unequivocally that drawing is what sustained me and gave me the strength to continue studying. From above, Hashem took care of me and provided me with the necessary tools, so I wouldn't fall, so I would persevere."

"Drawing Kept Me in Yeshiva"

Lipsker continues: "At the beginning of my time in yeshiva, I didn't quite find myself. My self-confidence was very low, and I noticed I could hardly speak fluently with my friends; I even started to stutter. It bothered me a lot, especially since I was a very sociable child and never lacked confidence. I always felt that I had something to contribute in this new setting but couldn't express myself, which was so frustrating..."

He says he quickly found himself during breaks and leisure moments, when other students engaged in discussions, unable to join in, sitting and doodling on paper. "I didn't think I really knew how to draw, mostly I doodled, but suddenly my chavruta noticed, and more boys gathered around, starting to ask what I was drawing. Even then, I still felt it was just doodles, but as those around me got excited, I started to realize there might be something here, maybe I really do know how to draw. This led me to draw more and more, and it created a kind of addiction for me. Whenever I had to deal with something, I'd retreat to paper and pencil..."

Nevertheless, he emphasizes: "It's not that I always received positive feedback. I remember an incident where a second-year student passed by my table, glanced at a drawing I had invested days into, tore it to pieces, and told me, 'Listen, it's ugly.' For a long time, I also approached dozens of authors and publishers asking if I could illustrate in their books for free, and none of them got back to me. But at no point did I give up. I always believed in what I was doing and simply kept drawing, explaining to my roommates excitedly, 'You'll see, one day I'll turn this into a profession.' At that time, I mainly connected with comic and caricature drawings, sometimes also drawing portraits of people, like friends around me, and trying to copy pictures."

But how did the yeshiva allow you to do this? What did the staff say about it?

"Perhaps it is indeed surprising, but in yeshiva, despite being conservative and very closed off, they clearly understood that it didn't come at the expense of learning, and even the opposite – the satisfaction from drawing strengthened me and gave me the desire to invest more in study hours. Later, in the big yeshiva, I even started to incorporate paid drawing work, not before consulting with the supervisor who told me I was the first in yeshiva to be allowed this, but on one condition – I wouldn't spend more than an hour and a half a day on it, and during the rest of the day dedicate the time exclusively to learning and not engage in drawing at all. That was the agreement that accompanied me through all my years in yeshiva, and I adhered to it with honor. I didn't even have an email in yeshiva, and on weekends I would return home to send all the materials I had prepared collectively."

After several years of study at the large yeshiva, Lipsker flew to Moscow, where he studied ritual slaughter and certification, continuing to paint in the meantime. "By then, it was already clear to me that my aspiration in life was to become an artist, and I tried to achieve and implement it. Not only as a hobby, but truly professionally."

Portraits or Nothing

About a year ago, shortly after the wedding, Lipsker realized that although painting was especially dear to him, to support a household, he needed to not only paint but also bring in a salary. This led him to reluctantly set aside the page and colors and turn to work in an insurance agency. "I did the job properly, but I always felt my hand couldn't rest, I had to draw, and at any given moment, I found myself doodling on small memo pages. At the end of the day, many doodles had accumulated."

Meanwhile, his young wife had an opportunity to see him drawing portrait pictures, and she was very impressed and naturally suggested: "Why don't you offer to paint people?" For him, this was a complete switch. "Until then, I was drawing for newspapers, mostly comics and caricatures, but I hadn't thought that portraits might catch on. But then my wife suggested that, and I started thinking, 'Why not?'"

To his surprise, the idea succeeded beyond expectations. "From the moment I announced I was painting portraits, I received many inquiries from people, some asked me to draw them or create a painting as a keepsake for someone close to them, or just a family picture, many also asked for rabbi portraits and other interesting challenges. After a short period of combining work at the insurance agency with painting, I started feeling I could no longer make dull phone calls while I had such an incredible tool in hand. So I left the office job and stayed only in the art world, enjoying every moment and experiencing great satisfaction. I now exclusively paint portraits; it's my only specialty today."

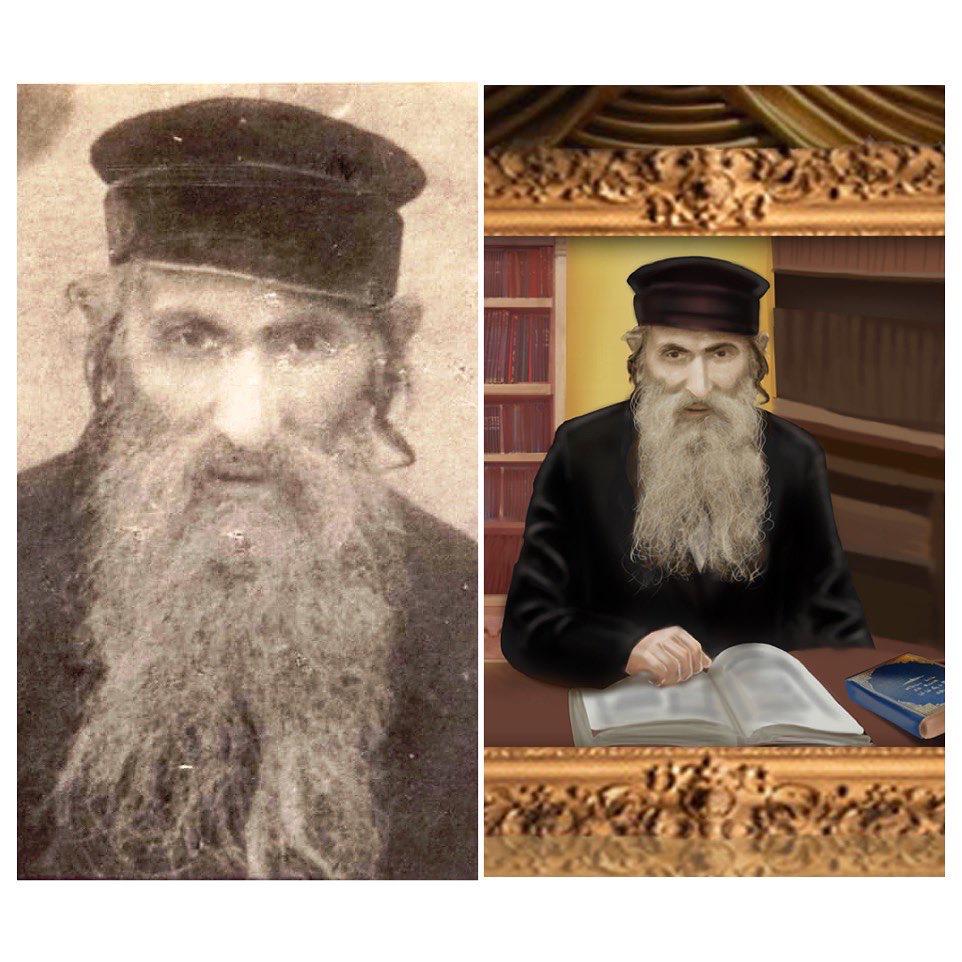

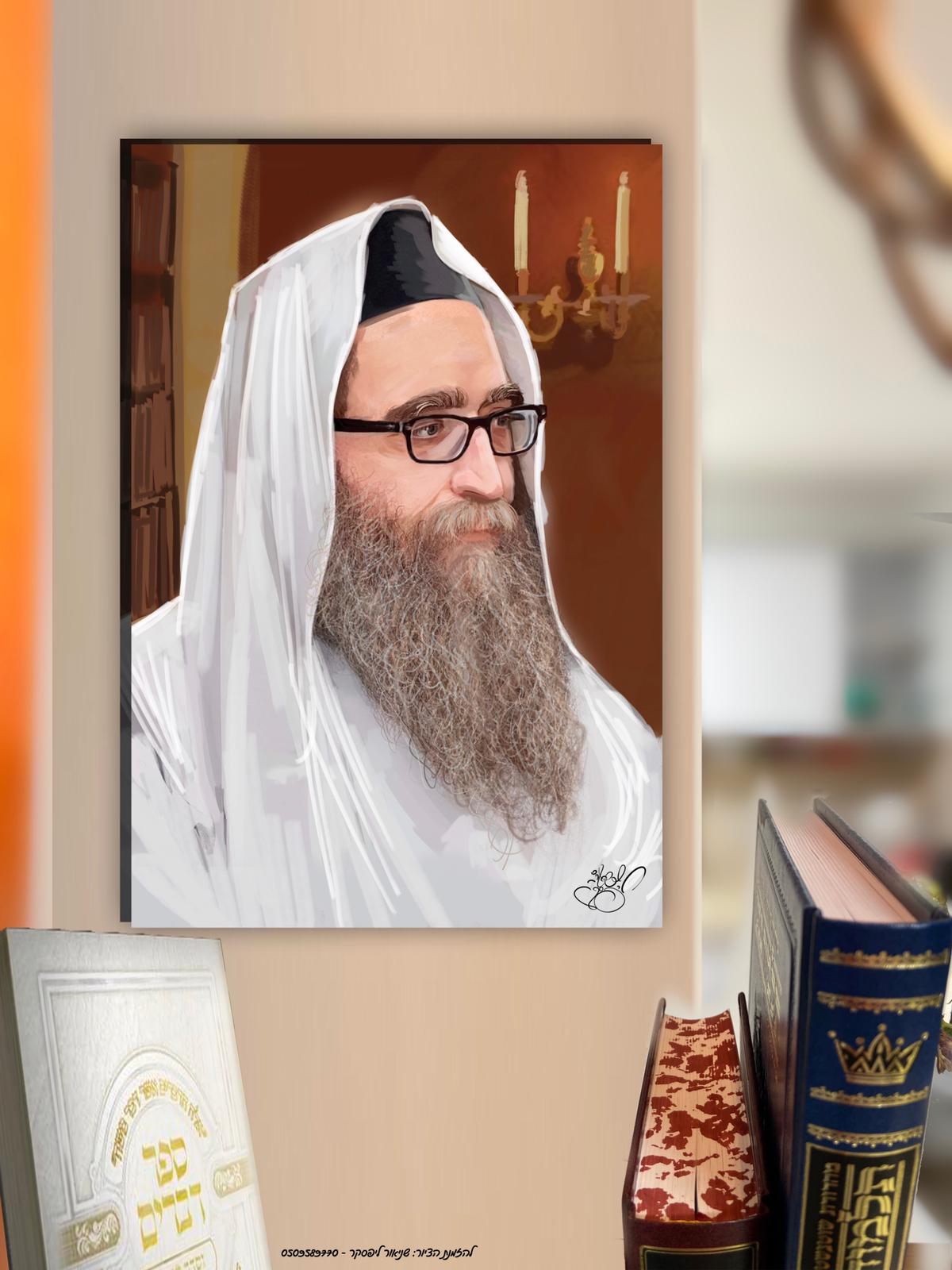

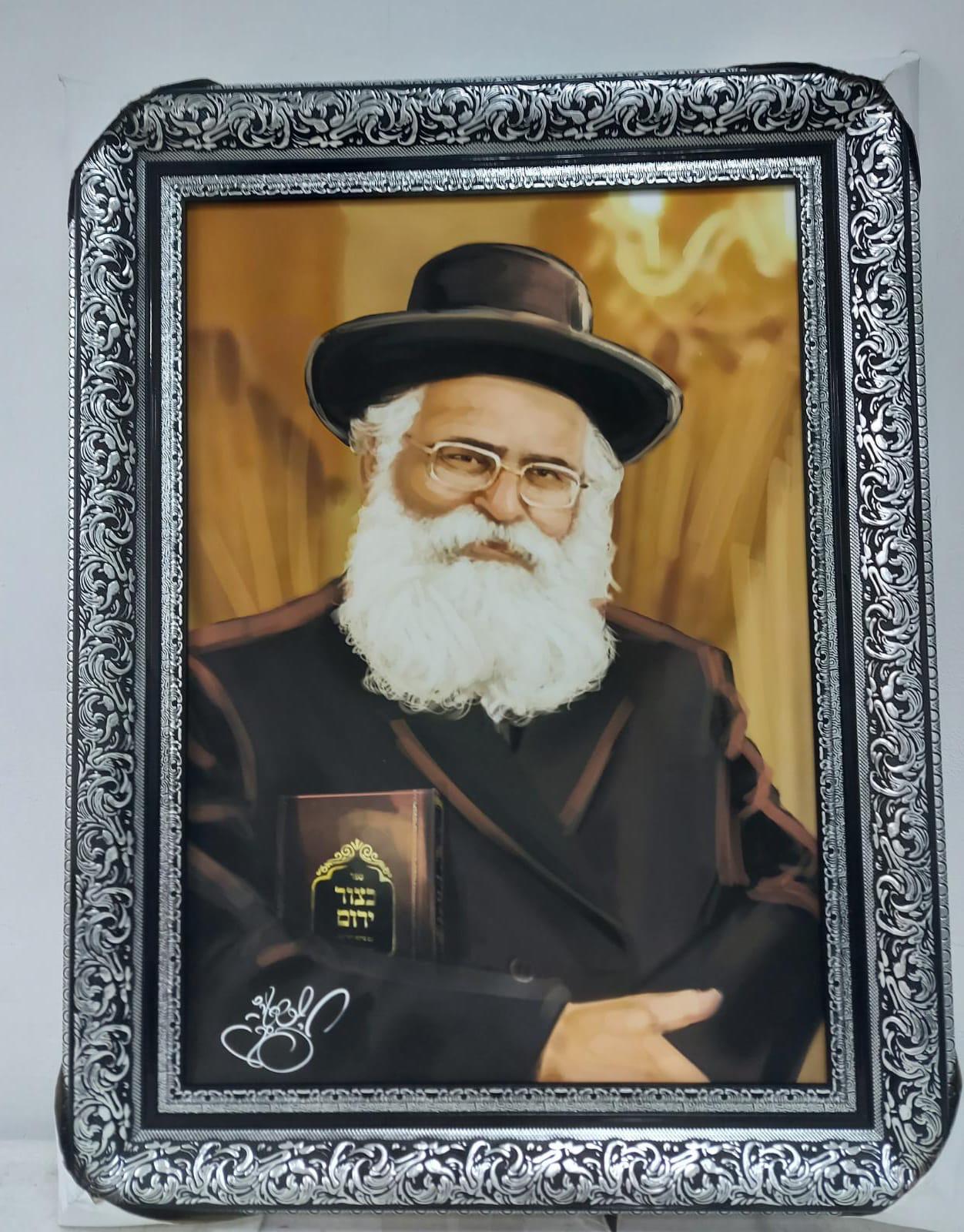

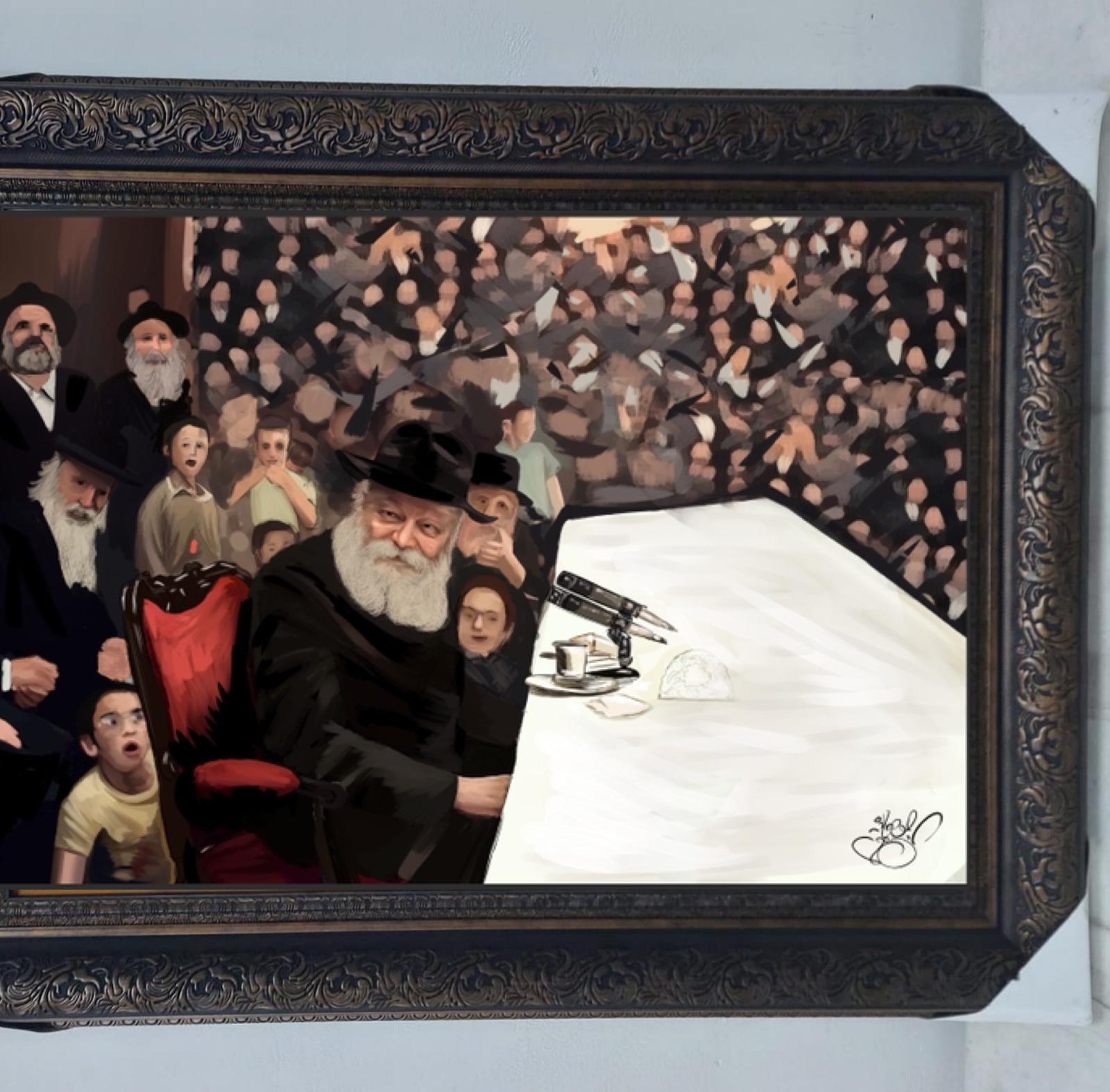

Numerous paintings have passed through his hands in the past year, but he finds the greatest challenge in painting rabbis. "When I'm painting such holy people, I feel like, in some way, I'm bringing them into my studio, and they are really present with me. This, of course, requires me to respect the atmosphere, to listen only to pure melodies while painting, and to treat it with great seriousness. In all my paintings, I dedicate a lot of time to painting the eyes and the gaze, where the essence of the character is reflected. When it comes to rabbis, I can spend long hours on this area, and it definitely demands a lot of me. I usually also ask for several additional pictures of that rabbi because although I draw one picture, when I rely on more pictures, I can get closer to the source and convey more depth in the painting."

And yes, Lipsker admits that sometimes, after hours or even days of work and investment, he concludes that what he drew is not expressive enough or doesn't meet the requirements, and so he leaves the painting aside. "Perhaps one day I'll return to it, and perhaps not..."

Are there characters you absolutely refuse to paint?

"As an observant artist, I don't paint anything immodest at all, and I emphasize this to people who approach me. I've also received several requests to paint people whose path I don't identify with, and morally felt I cannot paint them. In one instance, I was offered tens of thousands of shekels for a painting of a certain figure, and yet I refused because it completely contradicts my principles."

Finally, he wishes to candidly share: "When I started to draw regularly, I felt I needed great si'ata dishmaya, and one day I found myself talking to Hashem and literally saying to Him: 'Master of the Universe, You indeed want me to maximize my abilities and talents, and You also know how much I want to study Torah in addition to drawing. Let's make a 'deal' – You get me clients, and I will learn a page of Gemara each day.' During that time, something amazing happened – every day I learned a page of Gemara, I would receive a commission for a painting the next day. Just like that. I saw clearly that while learning is important in its own right, it also pays off financially. Since then, I strive to stick to it and not stop, not letting a day pass without learning. I know that's the key to success, more certain than anything else."