The Photographer of Redemption: 'I Didn't Want to Feel Like a Fool, That's Why I Returned to Judaism'

After leading a successful career as a photographer, accompanying political campaigns, and reaching the pinnacle of success, Kobi Klemenovitz decided to document Jews flying to Uman. This decision transformed his life, and now he shares his fascinating story.

Kobi Klemenovitz

Kobi Klemenovitz"I photographed across Israel and the entire world," says photographer Kobi Klemenovitz in his deep, measured voice. "There's almost no place I haven't been, and no photography style I haven't covered. Eventually, through these photos and seeing the infinite, I came to a clear conclusion – there's nowhere else I need to search."

He pauses and raises his eyes. No longer a young man, tens of years of photography, countless successes, and numerous documentations are behind him, with photos that adorned the nation's leading newspapers and famous magazines worldwide. "When I was young, I believed that the more I developed my photography career, the happier I'd become," he points out, "and listen to me – it's all nonsense. None of it really matters. Only after I began to understand these things did I draw closer to Judaism, marry, and today, with a huge family – my three sons from my previous marriage and ten children of my wife Chani from her previous marriage, as we are grandparents to almost 60 grandchildren – I can clearly state that this is the true success in life, everything else is secondary."

Without Judaism, Without Knowledge

Kobi Klemenovitz grew up in a home without any connection to Judaism. "My parents came from Romania," he recounts, "My father came from a religious home. I even have a prayer book that belonged to my grandfather, featuring the Vilna Script. My mother grew up in a home with Passover dishes, but her father had no problem with horse sausage. Initially, when my parents arrived in Israel, they lived in kibbutzim – my dad in Galil Yam and my mom in Giv'at Brenner. Judaism seemed to them archaic and irrelevant, something they weren’t interested in. The holidays and Shabbat were treated as default occurrences."

Kobi in his childhood

Kobi in his childhoodIn hindsight, Kobi recognizes several life events that laid the groundwork for drawing closer to Judaism. For instance, in second grade, when one of his good friends in elementary school returned to religion despite his family's reservations. That was when he first encountered Tisha B'Av... "It intrigued me," he says, "yet I didn’t really grasp its meaning."

During his military service, Kobi also felt the presence of Hashem on several occasions. "At first, I really wanted to get into a pilot course, but was disqualified over something trivial. At the time, I was very disappointed, but today I understand it was part of what led me closer to Hashem."

Those were the days of the Yom Kippur War, and while Kobi served as a keyboard player in the 'Sini Troupe' under the 252nd Division in Rafidim, one of the bombs fell just a few meters away from him. After his military service, he joined as a pianist and singer in 'The Populars,' a band formed by Uzi Chitman. Once an album was produced for the band, it turned out the manager had actually conned the band members, leading him to leave the ensemble.

The reality indeed changed, but Kobi's creative drive and strong desire to move forward did not wane. For him, it was clear that the next step was to study art in London, which he did. "For a year, I studied art at 'Saint Martins' – one of the renowned schools in London. It was a sort of general preparatory year in plastic art which introduced us to various fields within the realm of plastic art and through which, unintentionally, I was first exposed to the world of photography. From London, I moved to Paris, where I lived innocently with a non-Jewish girl, not realizing at the time that there was any problem with that. Even my parents, who came to meet the girl's family, had no objections to the relationship. Fortunately, Hashem worked things out so that I returned to Israel and she remained there. He protected me, and it's good that at that time I was still very impulsive – that's what saved me."

With a Camera in Hand

Upon returning to Israel, Kobi began working with various advertising agencies. "I was just starting out, and for most of the day, my studio in a rented apartment on Arlozorov Street in Tel Aviv was empty, I was desperate for work," he recalls.

One day, a job offer finally arrived. It was from a well-known advertising agency asking him to photograph cottage cheese for an advertisement. "This was my first work with advertising agencies," he says. "I was instructed to photograph the cheese against a very white background. I remember photographing, then taking a bus to my parents' house – where I had set up a darkroom. Upon developing the film, the negatives were filled with dirt, like salt streaks, and I felt awful. Additionally, the background turned out gray, not white. I realized that photography isn’t as straightforward as it seems and that I had a lot to learn to truly specialize."

This learning process repeated itself. "I learned everything the hard way, because there was no one to teach me and reveal the secrets of the profession," he explains.

Alongside his learning, Kobi's name began to spread, and work started coming into the studio. During those days, he was also offered an extremely lucrative job – a political campaign for the Likud party. "The funny thing is that I was as far from politics as the east is from the west, and I didn’t even know the party candidates' names," he recalls. "So I ended up participating in a political campaign almost without knowing whom I was photographing, and it certainly wasn’t cottage cheese... The next assignments I received came through various magazines, often feature stories or magazine pieces, where I was required to photograph opinion leaders who were frequently making headlines that week."

Were you overall satisfied with what you were doing?

"I was very satisfied, and in those days, I also married and later had three wonderful sons. Seemingly, I couldn’t have asked for anything better. The only thing that bothered and still disturbs me today is the low salary. In matters of money, there is no professional ranking – everyone is paid the same lousy wage. There’s no dichotomy between a senior and junior photographer; everyone receives the same bottom-line salary. Conversely, I saw a few friends from abroad who were lucky enough to reach a high, and even very high, salary. Some friends who studied with me at college in London had already purchased houses and luxurious cars."

This led him one day to a major annual gathering of photographers, photography agencies, and gallery representatives from around the globe held in Arles (a small town in southern France where painter Van Gogh lived). "I arrived with great curiosity and hidden hopes," he shares.

At that gathering, Kobi met another classmate from college who was living in London at the time, through whom he managed to access the gathering's celebrity cocktail. There, he found himself face to face with a Frenchman who headed the massive documentary photography agency Vue. "I don't know how I dared, but I simply 'initiated contact' and asked to meet with him. The next day, we met in one of the hotels in Arles, where I told him about the projects I was involved in. He showed interest, and it was agreed that I'd choose a subject for a documentary project and send it to him. It's worth noting that we're talking about the analog photography era, where the final product was a black and white or color print, and not files that could be instantly sent anywhere in the world. That senior person candidly admitted he didn’t guarantee to use the photos he would receive, nor would he return them. We closed the deal and parted."

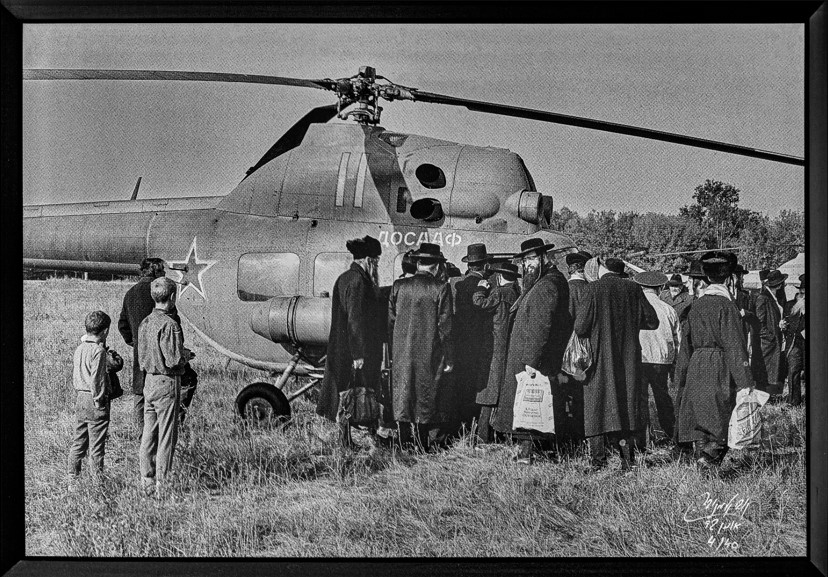

Around that time, another event occurred – Rabbi Amnon Gross, Kobi's cousin and his first influencer, often visited his studio in Tel Aviv during that period, leading to in-depth conversations about Judaism and life in general. "Rosh Hashanah was approaching, and I knew from my cousin that he was planning to fly to Uman for Rosh Hashanah, which wasn’t common during those times, done only by a few. At that time, a remarkable idea came to my mind," he recalls. "I told myself: 'This is the project,' deciding to join him on the flight to Uman. I arrived with only one camera, two lenses, 40 black and white films, and five kilograms of potatoes (everyone brought some food), planning to shoot a documentary project on the Hasidim at Rabbi Nachman – images I anticipated would be unprecedented. But there, after an intensive tour on the eve of Rosh Hashanah, lasting about half a day, with Russian military helicopters taking us to the graves of the holy Baal Shem Tov and Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berdichev, when we landed back in Uman, as I got off the helicopter, I realized I was already in a different place. In a deeply quiet but very determined internal decision, I returned to Judaism. Throughout the holiday, I didn't touch the camera, and eventually, I returned to Israel with new insights. This has been my path since."

Today, on the wall of Kobi's kitchen hangs a large black and white silk print – a photo he took in Uman that indeed gained tremendous resonance. In the photo, you can see a helicopter on the ground in a forest clearing not far from Uman, with many Hasidim trying to enter it, and on the side, several locals watching them curiously. This image was first published in a group contemporary photography exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum, and since then, in various places, it has become one of the hallmarks of the flights to Uman during times when this was not easy to undertake."

The famous photo from Uman

The famous photo from UmanOne of the questions Kobi often hears is: "What happened to you all of a sudden? What trauma did you experience that made you return to Judaism?"

"This question always makes me raise an eyebrow," he says. "In general, I don't think there's anyone on this planet, since Cain who hasn't experienced some trauma in their life. So I’ve gone through traumas too, but in my opinion, the traumas aren’t the main issue here – usually, if they don’t completely break you down, they strengthen you. I think, for me, it was something else – a feeling of distrust in the system simply developed within me. I felt like a fool, that an entire system was working against me, and I decided to investigate what was truly going on. I felt compelled to explore further to understand my identity, with a clear insight that no one would dictate to me what to do, except me myself."

What has changed in your work since returning to Judaism?

"Fortunately, even before returning to Judaism, I wasn't drawn to take immodest photos, so there wasn’t a significant change. But it certainly led me to refuse certain jobs, and occasionally, there were embarrassing situations. For instance, I was called to photograph a telecommunications CEO on a Saturday night, and I showed up wearing a frock coat and a hat because I hadn't had time to change. I knocked on the door, and when the lady opened, she thought I had come to ask for charity... So yes, the beard and my appearance can be intimidating to quite a few people I photograph, but ultimately, everyone calms down. To answer your question, yes, I try to adhere to halachic guidelines.

"In recent years, a new branch has been added to my professional life – contemporary Jewish documentation. About two and a half years ago, I shot a documentary project at 770, primarily focusing on the inanimate objects there. It's all under the inspiration of 'A Stone Shall Cry Out from the Wall' – which is also the name of the book I'm planning to publish with Hashem's help. I also have plans to scan all the photos from the Uman project and produce a book from that as well. Meanwhile, I'm currently working on a personal project – photographing various figures ranging from celebrities to fringe individuals who possess a divine soul. It's clearer to me than ever that my profession is merely a platform for the mission of reaching out to hearts."

From the photography project: 'A Stone Shall Cry Out from the Wall'

From the photography project: 'A Stone Shall Cry Out from the Wall'***

Just before finishing, Kobi asks me to peek inside his vehicle and shows me a pair of knee pads. "I keep them for the coming of the Messiah," he reveals. "It’s clear to me that when that great and awesome day comes, I’ll be in Jerusalem and nowhere else in the world, and when the Mount of Olives splits in two, I assume many stones will fly around – so the knee pads will protect my knees in certain photography situations. I aspire to be the one running among the crowds to photograph the redemption, and if you wonder what I want to be when I grow up: I hope very much to be a photographer in the communication department of the Third Temple, and if possible, also be the personal photographer of the Messiah himself."

Excitement is evident in his voice as he elaborates: "Especially as a photographer who has seen it all and also constantly reviews the works of others, I observe how in recent years, Hashem is turning the world with such decisiveness and powerful force. You’d have to be blind not to see how we are at the end of the exile and the beginning of the redemption. So many unimaginable natural phenomena occur, nations slaughtering each other, Europe undergoing Islamization, and countless Jews purchasing homes in Israel. You can see before your very eyes how it’s happening, the redemption is practically here, and I aspire to be the photographer to document the revelation of Hashem in the world. May I merit it."