Chabad Envoy in Chernivtsi: "The Governor Announces Justice, and People Broke into Tears"

Eighty years after the Bukovina Holocaust began, the governor of Chernivtsi announced that he will do justice and return one of the city's major buildings to Jewish hands. Chabad emissary Rabbi Menachem Glitsenstein shares this excitement and reveals what Jewish visitors seek each year in Chernivtsi.

(Photos: The Jewish Community, Chernivtsi)

(Photos: The Jewish Community, Chernivtsi)In Ukraine, near the northern Romanian border, lies the city of Chernivtsi. For years it was recognized as the capital of the Bukovina region—a modern and beautiful city, full of architectural buildings, statues, monuments, parks, and green squares.

In the city, there is also a Jewish community led by Chabad's Rabbi Menachem Glitsenstein. "To be an emissary here means to live the history, all those years that passed since World War II until today, to feel the Jews who were here before, and to be in close contact with those living here now," he describes.

In the past week, the past and the present merged together when, in an unprecedented manner, the governor made a special announcement for the Jewish community, which Rabbi Glitsenstein wants to tell us about. But first—some history.

Tracing the Roots

"It used to be common to call Chernivtsi 'Jerusalem on the mountain'," says Rabbi Glitsenstein. "There were so many Jews there that it felt almost like Jerusalem. Over 50,000 Jews lived in Chernivtsi until World War II—from all streams and kinds. The city also had over 60 magnificent and active synagogues. The Jews were able to manage large businesses and assume senior positions, and they spoke more than five languages, due to the Austrians' rule until 1920. So they spoke German, most knew French, and due to proximity to Romania, they also spoke Romanian, Yiddish, and Hebrew. To this day, a few Jews who lived here before the war still reside in Chernivtsi.

"Another interesting point," says Glitsenstein, "is that although during the war the Nazis sent most Jews to ghettos and camps, seemingly leaving no Jews in the area, after the war, most Jews of Chernivtsi emigrated to Israel, the U.S., or other countries. However, all those who wished could return to Chernivtsi with the Russians' permission. Following the Soviet Union's dissolution, about 40,000 new Jews came from the surrounding areas, replacing those who lived there until the war. For decades, there was a very large Jewish community, but towards the 1990s, many emigrated to Israel, leaving about 1000 Jews, who are the ones residing here today.

"The Jewish community in Chernivtsi is not large," clarifies Rabbi Glitsenstein, "but because there are descendants of the 50,000 Jews who lived here until the war and the 40,000 who lived here after, Jews from all over the world come here for root-finding trips. We repeatedly meet elderly people coming to Chernivtsi with their children, grandchildren, and even great-grandchildren. They try to locate the homes they lived in, find familiar streets, and recall memorable buildings. Sometimes they are also looking for documents, like birth certificates or various records, and we direct them to the local archive and try to assist them. The city also has a large cemetery with over 70,000 Jewish graves, considered one of the largest cemeteries in Europe, where no grave has been destroyed. There is also a cemetery archive, and almost daily, we encounter families who have located their parents' graves and recite Kaddish for the first time in their lives. The stories we receive are extremely moving, and every time, we are amazed to hear them".

According to Glitsenstein, one of the well-known graves in Chernivtsi is that of Rabbi Israel of Ruzhin, known as the 'Holy Rabbi of Ruzhin,' from whom six Hasidic dynasties emerged. "The rabbi's grave is a pilgrimage site for thousands of followers who arrive throughout the year, with plenty of hospitality activities, prayers, and lessons taking place.

Rabbi Menachem Glitsenstein

Rabbi Menachem Glitsenstein"In fact," adds Rabbi Glitsenstein, "we divide our time between activities for the Jewish community in the city—managing Jewish schools and kindergartens, as well as holiday activities, prayers throughout the week, taking care of the kashrut issues, etc., alongside receiving numerous tourists who come here from all over the world. Incidentally, quite a few students come to study here, mainly in the field of medicine, and we try to help them too, and there are Jewish tourists visiting from the entire region as part of trips. Because Chernivtsi is considered a developed city, with malls, beautiful shops, a train system, and an airport, we try to welcome everyone, even large groups. It's important to us that Jews visiting Chernivtsi know they have an address here for any Jewish need, there is kosher food and people who would be glad to assist with any issue."

80 Years Since the Bukovina Holocaust

What about the non-Jews in Chernivtsi? Do you sometimes encounter anti-Semitism?

"Unfortunately, there's anti-Semitism everywhere in the world, but specifically in Chernivtsi, we don't really experience anti-Semitic incidents. It's important to understand that Chernivtsi has always been, regardless of the Jews, a city inhabited by people from various countries and cultures. This created a situation where there's an effort to accommodate everyone, and there's no sense that everyone must look or be the same."

Despite the lack of visible anti-Semitism in the country, the buildings of the numerous synagogues that once belonged to the Jews and were nationalized have not yet returned to them. "Out of the 60 synagogues that existed here before the war, we're left with only one active synagogue where three minyanim are held daily," explains Rabbi Glitsenstein. "The other synagogue buildings have been repurposed—some are now cinemas, a synagogue serves as the state TV building, and some have turned into hospitals. All were grand and invested structures, but the communists nationalized them, turning them into government buildings."

For years, as Rabbi Glitsenstein witnesses, the Jewish community never imagined there was a chance to regain even one of these buildings. The idea seemed hopeless, and they continued to pray at the only synagogue in their possession, but last week, an unexpected major change occurred.

It happened early last week, on July 7, the day exactly eight decades ago when the Germans gathered about 500 Jews deemed the most important in the community, including the chief rabbi, major professors, and other figures, in Chernivtsi. They were then led in a terrifying march to the killing pit. Thus began the Holocaust of Bukovina, and immediately after, the ghetto was established.

"Being a Chabad emissary in the city for the past 16 years, it was clear to me that we needed to hold a significant event to mark the 80 years of that historic day, and that's precisely what we did. We organized a very impressive event and invited the ambassador of Ukraine, ambassadors from Israel, the governor, and the mayor. We held several events and ceremonies—starting near the monument, then gathering at the city square before continuing to the killing pit. "The feeling was very mixed," he admits. "On the one hand, we commemorated a horrible day for our people—a true holocaust, murder, and massacre. On the other hand, you can’t ignore the fact that the Jewish people live on, and we get to host generations of Jews coming to revisit their roots. We also held a special and fascinating forum discussing the Bukovina Holocaust."

Back to Jewish Hands

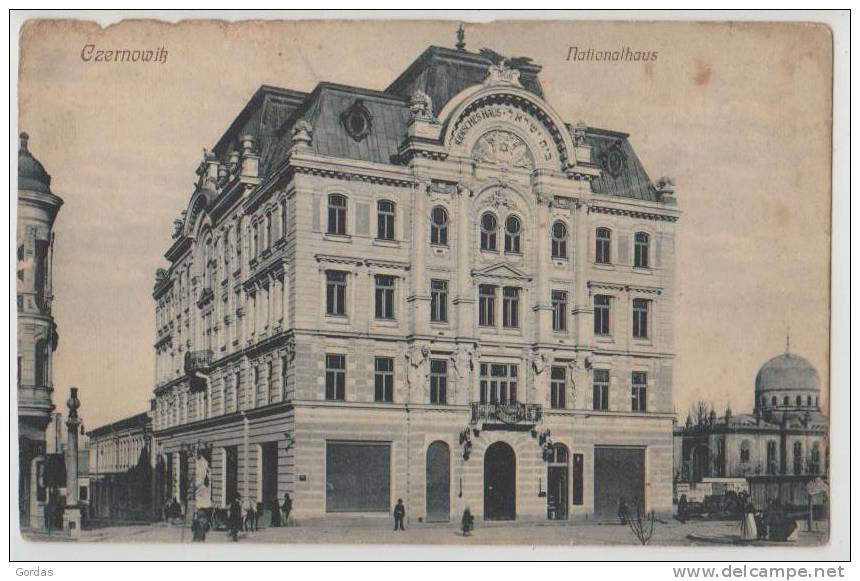

Then came the big moment that no one in the Jewish community could have dreamed of. "In the special event we organized, the governor of Chernivtsi announced to us that he declares a national justice, in which he will return the community building back to Jewish hands—one of the city's most magnificent structures, known as the 'House of Culture', offering concert halls and other cultural uses."

The building returned to Jewish hands after 80 years

The building returned to Jewish hands after 80 yearsEven here, Rabbi Glitsenstein says the reactions should have been mixed. "On the one hand, it is clear to us that this building is Jewish property; it belongs to us by right, not by grace, and perhaps we should even demand rent for all the years it wasn't in our hands... On the other hand, this is a very impressive step for the Jewish community—a step that hasn’t been seen in 80 years. Finally, this building, built by Jews and belonging to Jews, will return to its rightful ownership."

What do you plan to do with the building? What will it serve you for?

"We plan to use it as the community's school, as we lack classrooms in the current building. In addition, we plan to establish a Jewish Bukovina memorial museum inside and use the additional rooms for other community activities. In fact, most of our activities will move there, and the most exciting part is that after 80 years of the building being detached from Jewish life, Jewish life will resume there."

Rabbi Glitsenstein excitedly adds that after the declaration that the building would be returned to Jewish hands, elderly Jews came to him with tears in their eyes. "They told me how moved they were that the governor announced this building would be returned to Jewish hands, as for them, this is the city’s symbol, and until 80 years ago, it was also the clear Jewish symbol of Chernivtsi. It's impossible to describe the excitement."

The building today

The building todayAnd what about the other buildings in the city that were owned by Jews? Do you hope to get them too?

"There is an important building called 'The Temple'—in the past, it was the central synagogue of Chernivtsi, and today it houses a cinema. Mayor spoke about this building in front of the Israeli ambassador, expressing his willingness to return it to Jewish hands. We hope to receive it in the near year. Regarding other buildings—not discussed at this stage, but who knows, perhaps in the future?"