For the Woman

From Cancer to Kindness: Dikla Shotland’s Wig Donation Project for Women Battling Hair Loss

A survivor’s mission: donating and customizing wigs to help women regain confidence during cancer treatments

(In circle: Dikla Shotland)

(In circle: Dikla Shotland)Dikla Shotland created a wig donation project, born out of her own difficult experience. “For me,” she says, “it was the most natural, obvious thing in the world. Judaism teaches that the greatest thing a person can do is to take their own suffering and use it to prevent that same suffering from reaching someone else — especially someone from the Jewish nation.

“When I was battling cancer, I felt the pain with my entire body. I went through surgeries and harsh treatments, but one of the things that hurt me the most was losing my hair. When I understood the depth of that pain, I knew I didn’t want other women to go through it. That’s when I decided to take on the initiative of collecting wigs for donation.”

Dikla has lived through more than most people her age: she battled cancer twice — and recovered twice, thank God. “So how could I not thank Hashem?” she asks emotionally. “How could I not do everything possible to help women and girls who are ill?”

When the Sky Falls

“Do you see this huge box?” Dikla asks, showing me a large container packed with wigs donated by women from around the world. “I call it my charity chest. It's pure kindness — women donate their wigs, and I pass them along to oncology patients or women suffering from conditions that cause hair loss.”

She strokes the wigs gently. Most aren’t new; they undergo an intensive, professional restoration process before they can be matched to a woman who needs them. The work isn’t easy, but she blesses it, calling the project the greatest privilege of her life.

When I ask Dikla what inspired such a unique initiative, she takes me decades back.

Born Into a Home of Chesed

“I grew up in a special family rooted in giving. My father, Ezra Alfi, was a man of many accomplishments — a contractor who built in Israel and in Jerusalem. He adored this land and the Torah. He was known for his kindness: rehabilitating prisoners, helping families suffering from domestic violence, distributing food baskets — things that were not widely discussed forty years ago.”

Her mother, too, is a woman of profound kindness, the great-granddaughter of the well-known Rabbi Mulla Asher Garji from the Afghan Jewish community. “Chesed was something we absorbed into our bones from childhood.”

When Dikla was 18, her father passed away from cancer. “It was a devastating blow,” she says. “When we sat shiva, more than 3,000 people from around the world came to comfort us — great rabbis, members of Knesset. It showed us how great and special he truly was.”

She married, built a home, and then — after becoming a mother of two, her world fell apart again.

“One morning I woke up and saw a black screen in front of my eyes,” she recalls. “I thought it was low iron or blood pressure. Blood tests came back abnormal. I went through every scan — bone mapping, lung X-rays — everything looked fine. Finally, a doctor felt my neck and said she sensed a lump. She sent me for a neck ultrasound — and that’s where they found the cancer.”

Hair Loss = Loss of Identity

At first, Dikla tried alternative treatments. “I wasted a month and a half on a ‘healer’ who charged 500 shekels for 20 minutes, looked into my iris, and told me he saw no cancer. Then he gave me suspicious drops and told me to eat vegan. I tried it for two weeks until my husband forced me to go to Hadassah Ein Kerem. Professor Dina Ben-Yehuda — an incredible doctor, saved my life. By then the cancer had already reached stage 3.”

The treatments were brutal. “I remember praying through tears: ‘Hashem, You took my father from this disease, and my aunt. Please — don’t take more from our family. I want to live. Let me raise my children, and I promise I will add more kindness to the world.’ I emphasized chesed — because that’s how I was raised, and I felt that was exactly what Hashem wanted from me.”

The Hardest Part

Trying to maintain normal life during cancer was nearly impossible. “My husband and I are socially active; usually we’re the ones helping everyone else. Suddenly we were alone fighting cancer. We avoided unsolicited advice and opinions. We focused all our energy on one goal of saving my life.”

During her illness — and again years later, when the cancer returned, Dikla noticed a powerful pattern among the women she supported in her own support group: “The hardest thing for many women, again and again, was losing their hair. I also felt it as a deep personal blow, and nobody was there to comfort me through it.

Women described hair loss as losing their identity. It’s even harder than death,” she says quietly. “Because death is invisible. Tumors are often invisible. But a woman sees her face every morning. If her face is swollen from steroids or gaunt from treatments, that’s what she sees. And if her hair is gone — she feels she has lost herself.”

Only Good News

That painful truth is what pushed Dikla into action: a wig-donation initiative for patients.

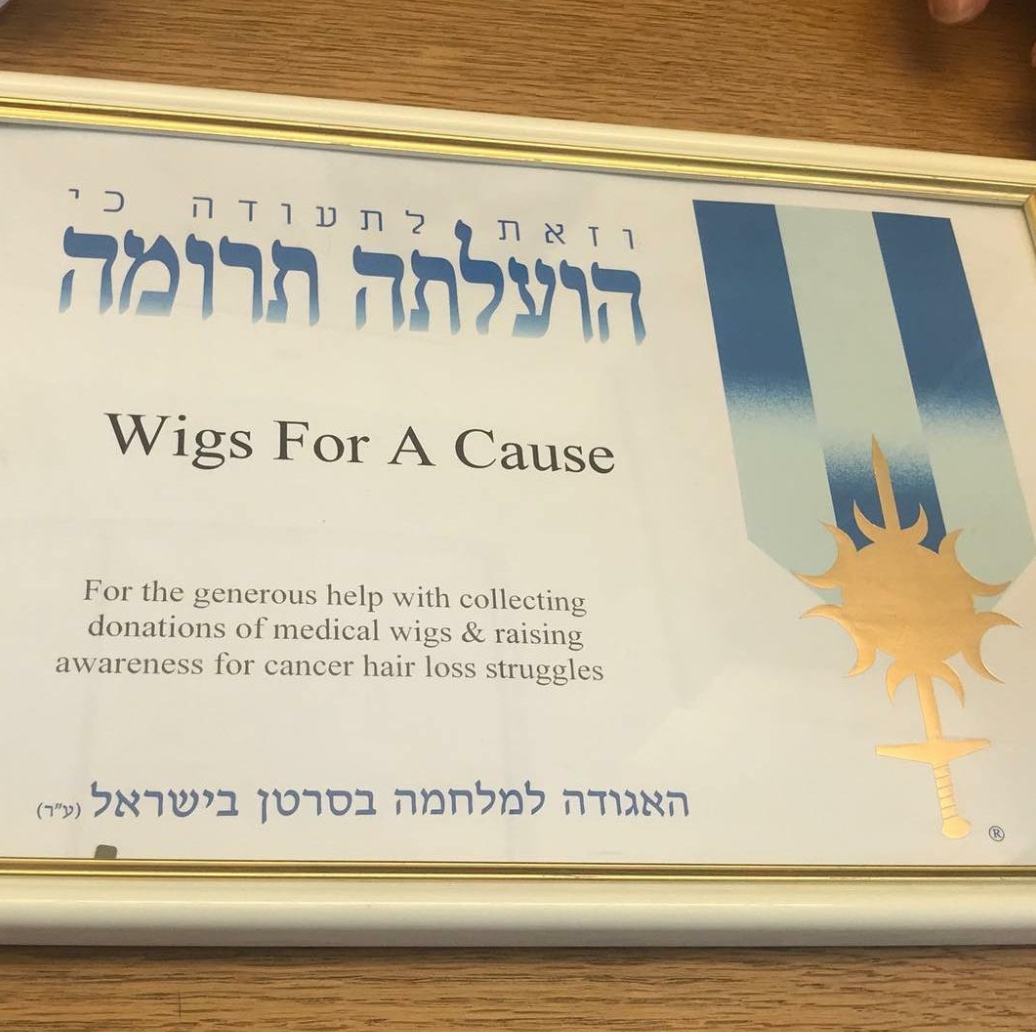

“Right after I recovered, I enrolled in professional wig-making courses. I opened a salon called Charlotte Couture & Wigs. I had learned the profession earlier, so it came naturally. On my own I donated around 100 wigs to women battling illness. I didn’t speak about it much, but word spread in my family and community, and women began giving me their own wigs to refurbish and donate.”

The greatest joy? “Matching the right wig to each woman. A woman shouldn’t settle for a wig that doesn’t suit her. She deserves one that truly honors her.”

Stories of Miracles

She shares a moving example: “A 19-year-old girl from Hadassah’s oncology ward came to me. She had beautiful strawberry-blonde shades in her hair and was told it would all fall out. She said she always wore a braid and wanted a wig she could braid the same way.”

The next part feels like Hashgacha Pratit (Divine providence): “Just the day before, a woman from the U.S. donated a wig in the exact same color and length, with identical highlights. It was hand-tied, with a lace that allowed for a French braid. After customizing it and blending some of the girl’s natural hair in the front — she looked breathtaking. We both cried.”

Another story: “I once approached a woman leaning against my salon door who looked homeless. Only when I came close did I realize she was the woman who’d called the day before. She was stunning but wore a short synthetic wig, had no eyebrows or lashes, and looked shattered.

“I brought her in, fitted a gorgeous natural-hair wig, and instantly she looked royal. She cried: ‘I feel like a queen.’”

Balancing Pain With Joy

Isn’t it hard to be surrounded by illness every day? “Of course it is,” Dikla sighs. “Each woman brings back memories. But someone who forgets her past can’t move forward. When I tell women, ‘Look at me — I suffered terribly, and yet here I am, able to help others’ — that message itself is healing.”

For balance, she also works with brides — creating wigs and bridal crowns. “I always bless them: ‘Only good news.’ It’s my way of blessing them — and myself.”

From Struggle to Triumph

Dikla’s wig-donation project continues to grow. “It runs completely separately from my business. I have a special ‘wig box’ where donated wigs go. I never reject a wig. I reuse every single one — sometimes as hair pieces for thinning hair, sometimes for men, sometimes for women with alopecia or fallout from other conditions.

“Women from every background come — every community, every level of observance. That’s what’s so beautiful.”

Having lived the illness herself, she encourages every woman who comes: “I always tell them: ‘Don’t look at me as someone who built a big business. I came from dust. The beauty of the Jewish people is that we know how to rise from the ashes.’”

Fighting for Survivors’ Rights

Dikla has also become an advocate for survivors of serious illnesses.

“People who recover still suffer from chronic fatigue, sensitivity to the sun, need for fresh air — yet they are given almost no rights. Not even disabled parking. It’s an area no one fights for enough. I try my best to raise awareness.”

She has created support groups for patients and survivors, and even a group called ‘Oncology Joy-Bringers’ that organizes volunteers to visit hospitals and bring gifts, books, and games directly to children.

“I remember how desperately I wanted someone to just understand me. I don’t want anyone else to feel alone.” “Not everyone goes through cancer — but everyone faces something. Let’s take our struggles and turn them into victories.”