"When My Little Brother Was Born, My Father Sat on a Stone and Wept"

Living in a tent, the poverty, lack of facilities, but also the joy and faith. Bnei Asher, who lived for 11 years in a transit camp, took on the initiative to document the lives of families in the camps. He now has 2000 testimonies, and he isn't satisfied yet.

Bnei Asher

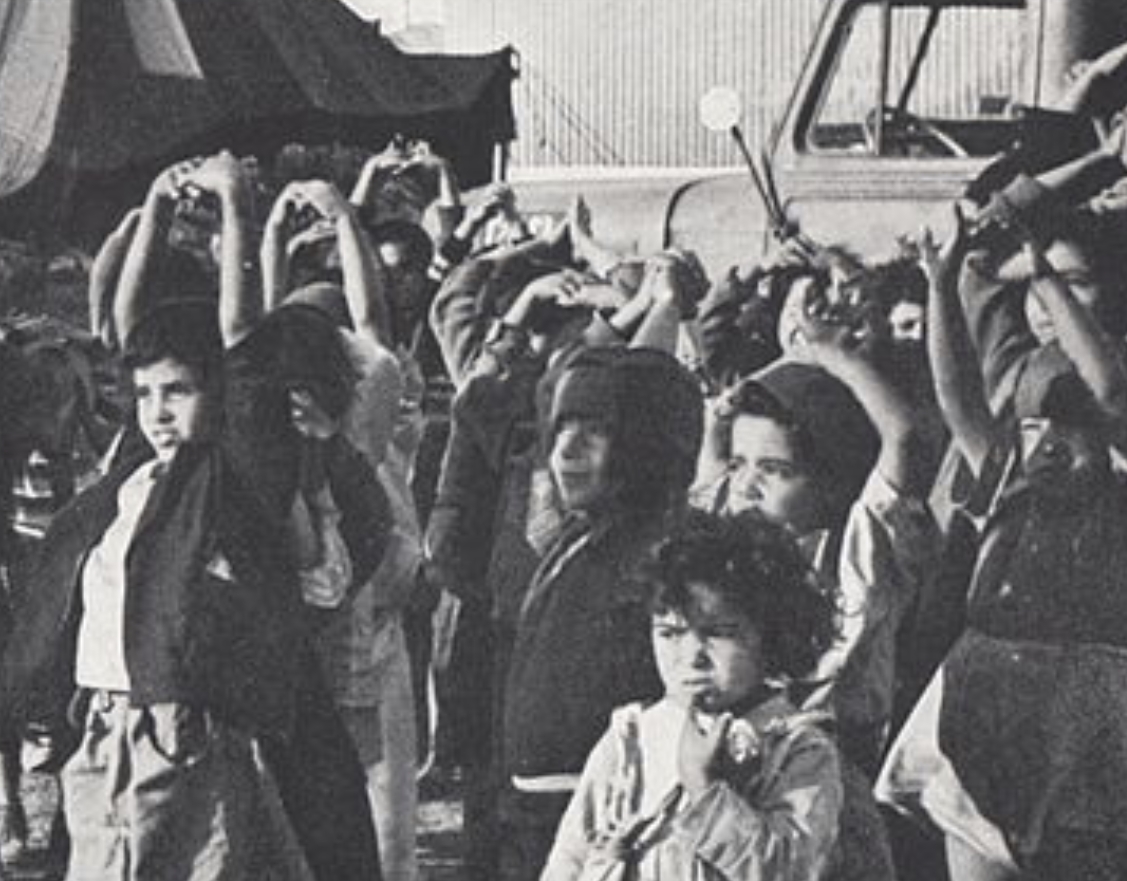

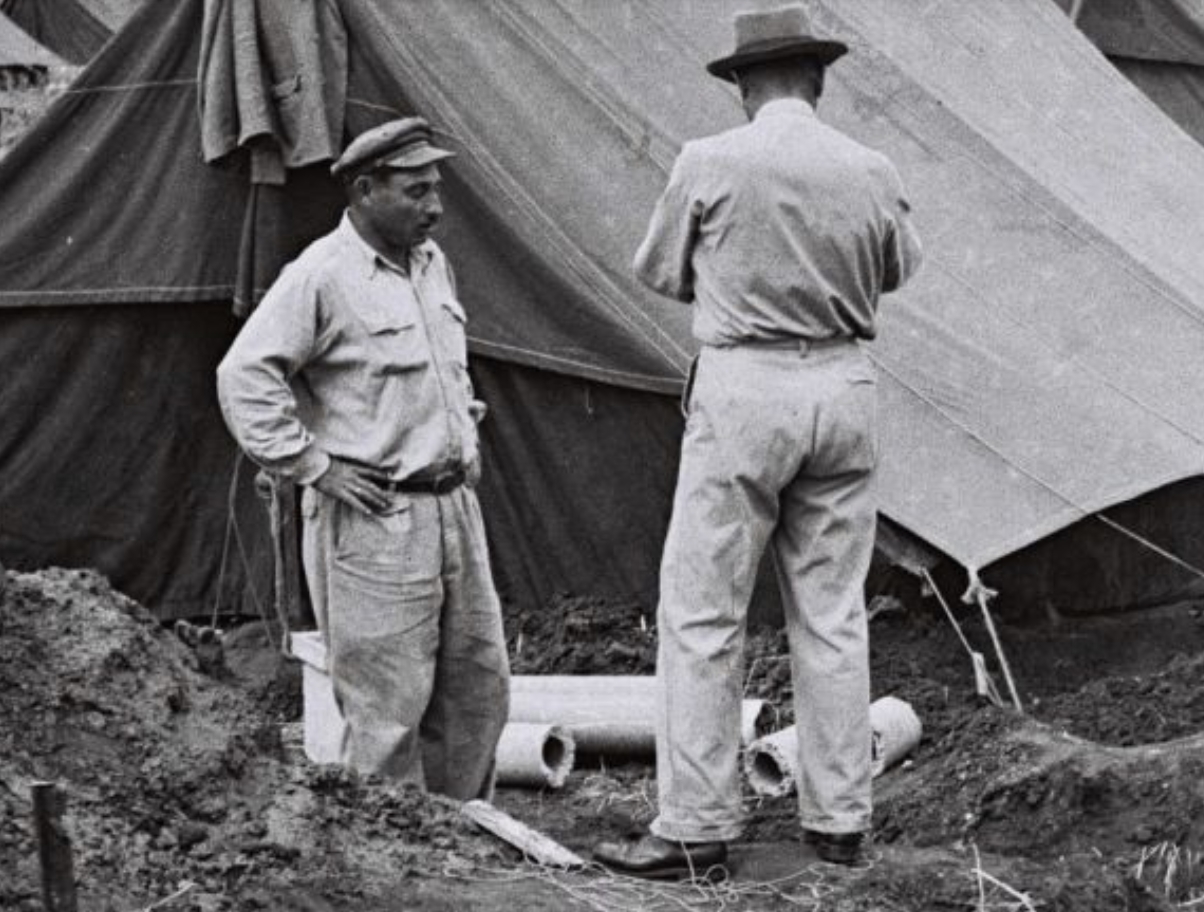

Bnei Asher"When I look at pictures of the new immigrants from the transit camp era, I cannot help but wonder," Bnei Asher, 75, tells me. In recent years, he has taken on the heavy task of documenting life in the camps during the establishment of the state. "Every time I am surprised again," he adds, "because I see the immigrants standing in the mud, by the tents, dressed in rags and without shoes, and yet they are smiling. These smiles, which seem so illogical, illustrate more than anything what that period was like."

Bnei himself grew up as a child in these camps, and as he notes, his memories from those days are only from the perspective of a child. However, most of those who were adults in that era are no longer with us, and even those who live among us do not always cooperate happily to reminisce about those challenging days. "I try to gather as many testimonies as I can, and my greatest enemy is time," he notes with concern.

As a result, he does not rest for a moment. "I work with other volunteers, and together we document people and gather testimonies from all over the country, from all backgrounds and from those willing and ready to share their personal and family stories with us. Sometimes we search for them like finding a needle in a haystack, and even encourage them to speak, as it is not easy for everyone."

How many testimonies have you gathered?

"We have about 2000 written testimonies. Of course, we haven't finished yet; we continue to seek interviews, we keep documenting."

Childhood in a Transit Camp

Bnei himself grew up in two transit camps. "At the age of four, I arrived in the country with my family from Egypt, and we were housed in the Rehovot transit camp, then called 'Ephraim Neighborhood.' We lived in a tent for two years, and later moved to Kurdi'ani B, a camp between Kiryat Yam and Tzur Shalom, where we lived for an additional five years."

Five years is a very long time in a transit camp...

"It's a long time, but as I found, when it comes to a transit camp, there's really no such thing as 'too long.' It turns out that each person who was there has a personal story different from the other. Some lived in the camp for a week or two, and then were immediately moved to permanent housing. Usually, these were families with relatives in the country who advised them on how to obtain permits allowing them to leave the camp soon. There are also those who lived in camps for just a few months, and others, like me, who stayed for years. I also met people who lived in a camp for more than ten years, sometimes voluntarily, occasionally because they had some business in the camp, or sometimes because they were promised land rights if they stayed."

"I interviewed a very dear Jew," Bnei recalls, "who told me that as a child, they wanted to leave for permanent housing but didn't have money for a moving truck. As a result, he wrote a letter to Ben-Gurion detailing their dire situation, and a few days later, suddenly two well-dressed people came with an envelope containing a considerable sum of money. They told him: 'This is from Ben-Gurion.'"

"When the man told me about it, he was tearful, and he explained to me that each time he tells the story, he cries again because it illustrates the level of poverty he lived in with his family. They didn't even have money to move."

"My parents also found it very hard to adapt to the poverty and squalor in the camps," he adds. "While we lived in the Rehovot transit camp, my little brother was born, inside the tent. Later I learned that my father sat on a stone and cried when he heard he had a son. He remembered Alexandria, where when a baby arrived from the hospital, there were silk sheets and luxurious bedding waiting, unlike here where he had to bring the baby into a dirty tent."

"Yet still," insists Bnei, "I had an amazing childhood, and I really enjoyed living in the camp. Our parents were very busy, and we, the children, were free. I learned to fend for myself, turn junk into toys, explore the spaces, and enjoy even the small things with my friends."

A Mosaic of Life

The graduates of the transit camps interviewed by Bnei for his project are those who came to the country from a variety of nations – from North Africa and Romania, from Yemen and Hungary, from Poland and Djerba, and basically, where not?

Already at the port, they were informed that they "are being taken care of with a place to settle," and soon they were moved to the camps, or officially named 'absorption settlements.' They lived there, often for long years, without electricity and hot water, in shacks or tents, and frequently in flimsy tents. In rains and winds, as well as in scorching heat. The first transit camp was established in 1950, but within two years over 220,000 people lived in the camps.

"I call this big mosaic the 'transit camp period'," he notes. "The special thing about this mosaic is that it contains many stones, in all kinds of colors. Each person is a special stone, a unique color and shape, and together they form the big mosaic."

Bnei doesn't only record the new immigrants, but also the native Israelis who took them in. "There were so many volunteers – young and old, who came to us from nearby kibbutzim and from Kiryat HaYam and Kiryat Motzkin, teaching us Hebrew, performing plays for us, engaging us... We loved them a lot; they helped us integrate into the country."

Why do you think it's so important to commemorate the transit camp period?

"Of course, there's the nostalgia and the storytelling experience, but beyond that, I'm sure there's a significant chapter in the story of the rebirth of the Jewish people in the land of Israel. Think about it – people from all over the world and from all communities came here, and they were the ones who eventually built the state of Israel. Their pasts are different, but they all share something – they heard there was a state, and simply got up and moved to the land. This is, in fact, what kept them going through tough times. They always said to themselves – 'Yes, the conditions are not simple and there are many challenges, but we are finally in our land, our state, we are not subjects of anyone, and nobody can expel us or kill us in a pogrom.' Anyone who didn’t come to the land in those days simply cannot understand the feeling, but that’s exactly what helped survive the transit camp, despite all the difficulties."

What was particularly difficult about the transit camp?

Bnei sighs. It's clear he prefers not to talk about the hardships, yet he clarifies: "In the overall story of the camps, there is quite a bit of suffering and hardship. There's the well-known story of the Yemenite children, and not just them, who were taken in one way or another. I personally experienced a kidnapping story within my family when my aunt's baby disappeared, and to this day, there are no traces of her. I do not ignore these stories, but they are so-to-speak negligible, because overall, the activity of the camps was blessed and necessary."

You say negligible, but these are stories that ruined families' lives...

"True, I do not deny the difficulty. As a child, I also saw the great struggle my parents went through, the suffering was evident, and I also heard the cries at night. There were times I saw my father coming home early from work because he hadn't received any work that day and, of course, no money. So he went to the grocery to ask for a delay in payment, and the vendor would angrily shout, and it was a great humiliation."

"There was also the unforgettable day, when a terrible train accident occurred, resulting in the death of 12 people and injury to 23 when a passenger train collided with an Egged bus carrying workers from our camp to their jobs in Haifa. Naturally, we knew all those who were killed or injured; it was a horrible shock, a disaster that cannot be described in words. As a result, we planted a small grove that same year, and ever since, every time I pass by, I go to check on 'my grove.'"

"By the way," he adds, "this led me to connect with various authorities whose territories once had transit camps and to suggest an initiative to bring adults and children together to plant trees where the camps were. The children will continue to monitor the trees throughout their lives, thus we will have a remembrance of the camps that were and are no more."

Transit Camp Shapes Life

"You asked why it is important to commemorate the transit camp subject," Bnei returns to the topic, "and there is also another reason - I believe it's crucial to salute those heroes of those days. I don’t mean me or my friends who were children then, but our parents, who seem to have been forgotten. I only awakened to this four years ago, at the age of 71. Suddenly I thought to myself that we, the children of the camps - we've grown, started families, and even became CEOs, engineers, businesspeople, and security personnel, while most of our parents were left behind. Many continued to suffer from a reputation of poverty and underdevelopment for years. By the way, this reputation unfairly clung to them, as the camp had amazing initiatives and many innovations and interesting ideas."

"Additionally, it's important to document the days of the transit camps also to learn what needs to change, and how not to repeat mistakes. It's quite common to establish commissions after wars to examine the management of affairs during the war, even if they were successful wars. Likewise, the transit camp topic should be treated similarly. We all enjoyed the success, but research is needed to understand what exactly happened, and to become aware of both the good and the less favorable things."

This is Bnei Asher, with one of the grandchildren

This is Bnei Asher, with one of the grandchildrenWhat, for example, would you propose to change?

"I have an endless list of things needing improvement, but it must be remembered that in those days there was a tangible shortage felt daily. We were only a young country emerging from a war, victorious indeed, but in absolute poverty. I remember as a child hearing about a ship full of wheat that arrived at the port but couldn't be released because there was no money. Ben-Gurion had to send a delegate to America to obtain the necessary funds to bring the wheat into the country. So it’s hard to really blame anyone."

Yet with all that, he also emphasizes: "When I interview people, I ask them standard questions, but at the end, I ask them in their own words to state three points they believe are important about the transit camp. Almost all of them tell me a concluding sentence: 'It was hard, but it was important because the camp shaped our entire lives.'"