Tzviah Taybi: "My Father Jumped Out the Window with My Brother, and I Followed Them"

In Yemen's Sana'a, Tzviah Taybi fled with her family on a truck and donkeys only to find her brother missing and her baby daughter taken from her upon arriving in Israel.

The Arusi Family in Sana'a

The Arusi Family in Sana'a"Recently, we hear so many revelations about new findings concerning the kidnapping of Yemenite children," says Tzviah Taybi, letting out a heart-wrenching sigh that reveals the deep pain the topic causes her. "On one side, I am glad to hear that justice is being sought, but on the other — will this bring back my daughter? The baby taken from me 70 years ago?"

Her question hangs in the air as she adds, "There's so much talk about babies being kidnapped, but I have a younger brother, Avner Arusi, who was taken when he was still a child, from the camp hospital. It was only by a miracle that my father managed to get him back. I think of all the children who were stolen from their parents and never returned, and my heart cries. So many years have passed, but these stories never leave."

On Camels and Donkeys

Tzviah was born in 1932 in the city of Sana'a, Yemen. At the age of ten, she was orphaned when her mother died during the birth of her younger brother, and the burden of raising the family fell on her shoulders. "And it wasn’t a small family," she notes, "We had ten people in our family, and I took care of my younger siblings and all the cleaning at home. My father was a merchant and worked outside the home all day, so the burden fell on me."

Tzviah points out that this was also why they didn't look for a match for her in those days, contrary to the custom in Yemen where girls her age would have already set up their own homes. "I stayed at home all the time, and even after my father remarried and my younger sister got married, I still stayed home because it was clear that my help was needed."

A few years later, there was news of the establishment of the State of Israel, and excited talk about making aliyah began. "I remember the tremendous excitement there was," recalls Tzviah, "My father had many businesses, he was very wealthy, yet it was understood without question that he would leave everything in Yemen, and we would all go up to Israel. The other Jews living around us felt the same way. My father explained to us that we would have to go on a long journey, at the end of which we would reach the Hashad camp, and from there fly to Israel, and indeed we prepared for this journey."

How does one prepare for such a journey?

"When we left the house, we still didn’t know exactly how long it would take us to get to the camp, but it was clear that we would need a lot of supplies for the way. So I prepared rusks and took water pitchers. My father took care of the financial aspect – he took three large sacks full of money and gold, as well as tins full of jewelry and suitcases with valuable cloth. That was all our belongings, leaving behind the large house and other things."

The road soon revealed itself to be not only long but also very exhausting. "At first, we traveled in trucks – several families pushed into a truck, and we drove on bumpy roads," Tzviah details, "but then we reached the desert, where trucks couldn’t continue, so we switched to camels and donkeys. We rode them for weeks, almost breaking from sitting on the donkey."

Tzviah notes that the young children couldn't ride, so their parents put them in sacks, tying them to the donkeys. "That’s how it was with my younger brother Ratson," she remembers, "My father tied him inside the sack, and I was responsible for him and made sure he was safe. At night we would usually stop and rest by the side of the road, but sometimes when we reached a settlement, we would enter a hotel where they offered us food, a place to sleep, and shelter for the donkeys."

From one of these stops, Tzviah recalls a frightening experience: "My father entrusted me with taking care of his donkey, on which sacks of money and gold were tied, as well as a small sack with my little brother Ratson. I tried to sleep beside the donkey and suddenly discovered an Arab thief approaching and taking the donkey with him. The first thing that came to my mind was the concern for my baby brother. I tried to stop the Arab, but he had already escaped. I burst into cries and started chasing him with bare feet until I managed to scare him off and bring the donkey back. Although Ratson returned to us, as did the donkey, the thief managed to steal the money and gold. So we were left with only part of our belongings, but with great gratitude to Hashem that Ratson was saved. Today, he has become a great rabbi – Rabbi Zion Arusi, a member of the Chief Rabbinate Council of Israel and the Rabbi of Kiryat Ono."

Honestly, Tzviah notes that under natural circumstances, their other belongings should have also remained on Yemen's soil. "After we reached the Shahad camp, they gathered us to board the planes as part of Operation 'Magic Carpet,' but first demanded that we part with all the goods, money, and gold, even threatening us that 'if we load the goods – they might crash the plane.'"

Did you leave the goods in Yemen?

"Of course not. My father was very wise, he said the valuable cloths were our clothes, and we had to bring them to the land, and he packed the money and gold into thermoses, bringing them along. My father acted very cautiously and always taught us the concept of 'trust but verify' – we must thank all the Zionists organizing the aliyah but be very cautious and not trust anyone except ourselves."

Rabbi Arusi in Yemen

Rabbi Arusi in Yemen"Father Jumped from the Window"

At first, Tzviah and her brothers didn’t understand what their father feared, but later things became clear. "We arrived at the Hashad camp along with several families who joined us on the journey," she details, "There, they informed us that we would have to wait a few days until it was our turn to board the plane. The camp lacked good conditions, but there was a clinic, which was very important for us, because my younger brother, Avner, was ill and could receive treatment."

Tzviah notes that her father was very concerned about Avner and instructed her not to leave him alone even for a moment. "One day, they announced our turn to board the plane. Father asked what would happen with Avner, and they explained that he would stay in the camp and come after us. Father refused to hear of such a thing. He pulled Avner from the clinic, and we boarded the plane with him."

The next chapter in Tzviah’s life story was in the Ein Shemer transit camp. "When people say 'ma'abara,' they immediately think of tents, but we were among the first immigrants, so we were fortunate to live in a small shack. We crowded ten people into the shack, and this was after having a spacious, big house in Sana'a. Initially, we complained, but later, when we saw the scorching tents set up for those who came after us, we realized how lucky we were."

But there was more to Avner’s story. "When we arrived in the camp, Avner was taken to the hospital room, and my father continued his strict instruction – never leave Avner alone. Already then, stories began to circulate about kidnappings of children, and father warned us all. We made shifts – sometimes father would be with Avner, sometimes his wife, and sometimes me. One day father told me that Avner was feeling better and that I should go be with him in the hospital room, but when I arrived, the nurse told me that 'the child has died,' and when I asked how this could be, she consoled me by saying, 'don’t worry, you will have another baby".

How did you react to such terrible news?

"I didn’t lose composure," Tzviah recalls, "I ran to my father, and he realized in a moment what had happened and informed me that we were going out of the ma'abara and looking for Avner. It was the first time we left the camp, I ran with my father along the hot roads, our bare feet burning, until we finally found a Yemeni who immediately understood what we were talking about and directed us to the Dajani hospital in Jaffa, where he claimed they were hiding kidnapped children.

"We reached the hospital, and I must say that I didn’t believe there was a chance we would find Avner. But my father entered the ward and managed to shake the walls. He shouted that he was looking for his son and demanded to know where he was. We went from room to room and didn’t see Avner until we reached a side room where there was a group of children, and among them was our Avner. Father didn’t hesitate for a moment, despite being a dignified and composed man, he jumped to Avner, wrapped him in a tallit, and jumped out of the window with him. I understood that father had done something seemingly illegal, so I ran after him, and we all fled from the hospital, hearing police sirens chasing us. We kept running until we reached the tent housing area, where we hid in a family member’s tent until things calmed down."

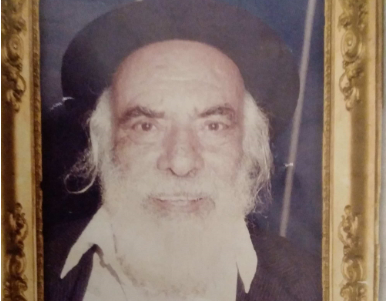

Rabbi Arusi father of Tzviah

Rabbi Arusi father of Tzviah"They Told Me: 'There’s No Baby Girl'"

In 1950, Tzviah married her husband Zechariah Taybi. "I was 17 then – very old by Yemenite community standards," she says, "I then worked as a cleaning worker at a health fund and later advanced to lab assistant. Meanwhile, I completed reading and writing lessons."

Tzviah notes that she has two sons, but before that, a baby girl was also born. "And she was taken from me," she emphasizes, breaking into tears. "I still remember how she looked – so perfect, completely healthy..."

What do you mean by "taken"? How did that happen?

"The truth is, I initially feared giving birth in the hospital. Rumors had reached the camp about baby kidnappings, and I also had trauma from the Avner incident. On the other hand, I feared giving birth at home. Our living conditions were so hard that we couldn’t even shower properly. I thought that in such conditions, the right thing for me would be to give birth in the hospital, and so I went to the Dajani hospital in Jaffa."

After the birth, she held her baby girl for a few moments. "A beautiful and perfect baby," she repeats, "then the doctors asked to take her for tests, and from that moment, I never saw her again."

Did you ask for an explanation? Didn't you ask where she is?

"Of course I asked. At first, they sent me from room to room, and finally, one of the nurses told me: 'There’s no baby, she died.' I started to go wild and scream. I told her: 'I saw the baby, she’s alive and healthy, tell me where she is.' The nurse referred me to the doctor, and he just said: 'It’s over, you have no baby, she doesn't exist, nothing at all.'"

Tzviah's voice breaks as she recounts that she didn’t give up. "I looked for her all over the hospital, always thinking that they might have stolen her from me, but there was no one to help me, and after all, I had just given birth, which didn’t allow me to search far."

What did your husband say about it?

"My husband believed them. He truly thought the baby had died. Only years later, my daughter-in-law managed to obtain the baby’s birth certificate, but we didn’t find her grave, so there’s no proof that she died. In fact, we have no idea where she is today, and that’s what hurts the most because in my heart, I still feel she exists."

Tzviah mentions that this is also why she decided to participate in a documentary highlighting the story of the kidnapped Yemenite children. "It’s important for me to raise awareness, for people to understand what happened in those years. This is also what made me agree to be interviewed for this article, despite my age and the difficulty of recalling all the hardships we went through."

Do you think there is a chance that this publication will lead to finding your daughter?

She sighs. "I don’t know," she finally says, "I don’t want to think about it and hope, for years I hoped, and it just wounded me. But there’s no doubt that this issue must receive its place because it’s imperative to solve the mystery and understand what happened to these babies and children one by one."

Thank you to Shira Amrani, CEO of 'Mesilot' - Developing Employment and Businesses in the Periphery, for her great assistance in preparing this article.