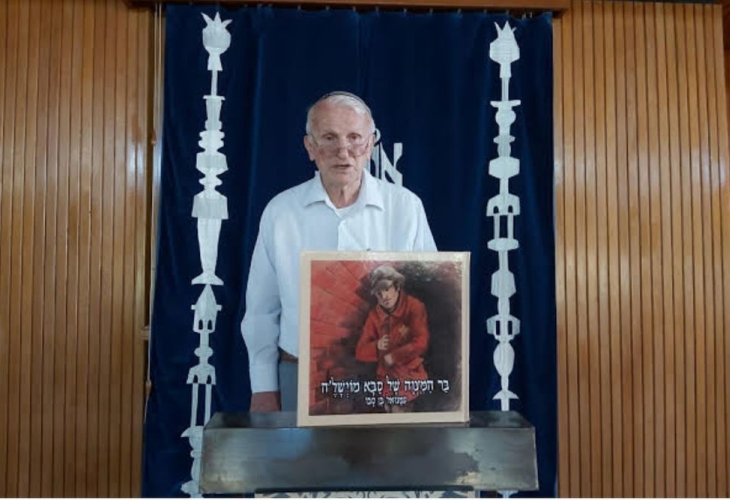

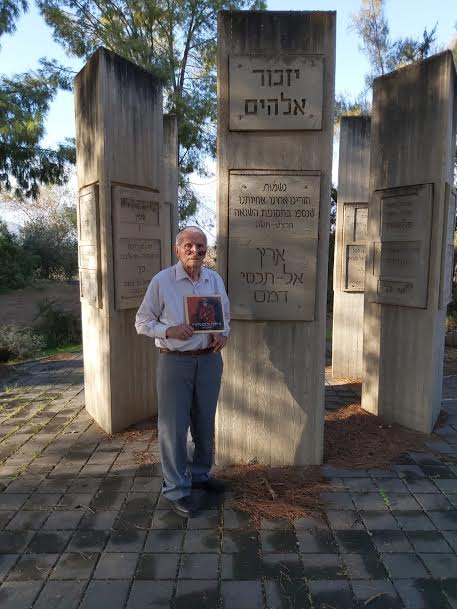

Moshe Porat: "70 Years After My Bar Mitzvah, I Am Honored to Share This Miracle"

The tefillin were hidden, and the Torah reading was done in secret. As a treat, there was some hummus. This is how young Moshe Porat experienced his Bar Mitzvah day. This week, he is eager to recount his incredible story and pass it on to younger generations.

Moshe Porat

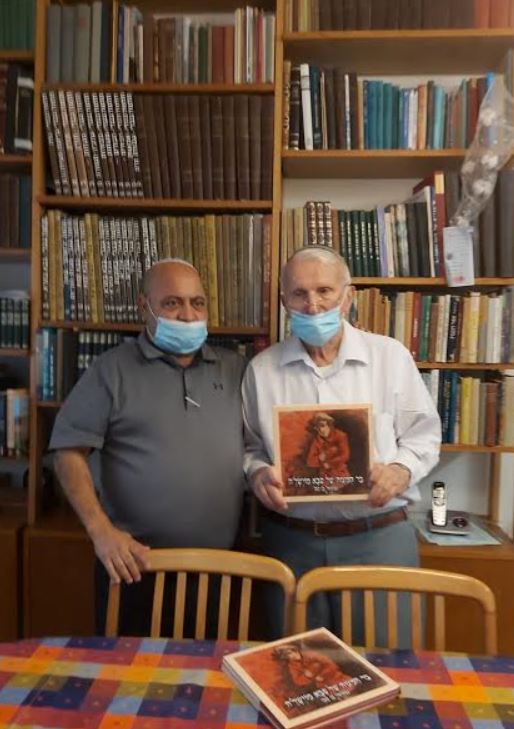

Moshe Porat"I will never forget my Bar Mitzvah day," Moshe Porat says to me with a trembling voice. Seventy years have passed since the day he came of age, but the scenes remain vivid in his mind. Now, he has another reason to be thrilled, as his story of survival during the Holocaust is being published in a book by author Emmanuel Ben Savo.

Emmanuel Ben Savo, also an educator and graduate of yeshivas, aims the book at young readers. It joins four other books that tell the stories of Holocaust survivors in a simplified manner for children.

Passing Stories to Future Generations

On his choice to focus on Holocaust literature, Ben Savo shares: "In recent years, I began to think that as we lose the last survivors, stories are growing distant from our present reality. The younger generation is finding alternatives and becoming less familiar with the stories we grew up with. That's why I initiated a small project, currently comprising five children's books. I call them: 'Jewish Character Representation Amidst the Holocaust Storm.'"

Ben Savo elaborates: "My first book is called 'The Shaking Candles.' It tells the story of a child who escapes the ghetto to get Shabbat candles. He finally gets one and takes it around the ghetto so all the Jewish women can light it. I felt there was great value in sharing this story to show children how, even in darkness and despair, Jewish women maintained their dignity and risked everything for a Shabbat candle.

"My second book, 'Candies of Life,' recounts the story of a remarkable man I met who prayed in my synagogue and handed out six colored candies. Talking to him revealed a story—he had five children and a wife, all killed in the Holocaust. He remained unmarried but every Friday bought 30 candies in six colors, each one symbolizing a child he had. He would distribute them to living children, those he saw as continuing his path. The remarkable man has passed, but his story lives on.

"Another book I wrote, 'My Brother,' shares the story of Yona Schlaisser from Afula, an Auschwitz survivor. In the death march, he carried his brother on his shoulders. At one point, his brother fell and couldn't rise. Yona tried to save him but was forced to move on by German guards. He never saw his brother again. The book portrays brotherly love, mutual responsibility, longing, and hope. Yona searched for his beloved brother until his last day, but it never bore fruit. Yona died a year and a half ago, seeing his book published just days before his passing as a tribute to his strength and brotherly love."

Another book—'The Little Beggar from Durban'—tells of parents I never met," Ben Savo says, "but comes from knowing their son. It centers around a beggar father who sneaked through ghetto fences in Romania to request alms from rural poor to feed his family. Against all odds, he and his family were true heroes. Later, the father built a great synagogue in Ra'anana. His son isn't religious by definition but splits his heart and charity open for every needy person."

My Uncle Asked, "Do You Want to Put on Tefillin?"

Last week, Ben Savo released his fifth Holocaust book, 'Grandpa Moishele's Tefillin,' featuring Moshe Porat's poignant story.

"It was over 70 years ago," Moshe recalls vividly and excitedly. "Days before being herded into cars led to extermination camps, we were at Umschlagplatz, crammed among 20,000 Jews from fifteen communities, sleeping on our bundled belongings. My uncle woke me at night, asking, 'Do you know it's your Bar Mitzvah today? Do you want to put on tefillin?' I knew it was, my father prepped me, but he'd been taken for forced labor four months before. I wanted badly to lay tefillin, but any caught with them received beatings. I feared greatly.

"Ultimately," he continues, "after much debate, I took the tefillin from beneath my pack and followed my uncle. While one doesn't lay tefillin at night, I went with him. In complete darkness, he wrapped himself in a tallit, and I placed the tefillin on my head for the first time, as my father had shown four months prior. My father insisted on exquisite tefillin. We prayed afterward. I don't remember what or how long, but I vividly remember the immense excitement. After finishing, my uncle took me to my mother. As I approached, I saw her worried face, realizing her tension once I disappeared. But once we returned, and my uncle told her I had put on tefillin, I saw her eyes spark. At that moment, I realized she'd prepared for the event, pulling some hummus and treats from a bundle for a 'Bar Mitzvah celebration.' Two days later, we were taken by train. Thus began and ended my Bar Mitzvah."

Ben Savo notes that Moshe Porat's profound story struck a deep chord. "About ten years ago, as the educational director of a therapeutic boarding school, I first heard it and decided on a kind of corrective Bar Mitzvah experience for Moshe with my students. At that time, when we met, Moshe shared more of his war ordeals. It turned out he'd endured much with his mother and four siblings, surviving miraculously in a brick factory. His mother fought like a lioness but died two weeks after liberation.

"Among all of Moshe's tribulations, the memory of his Bar Mitzvah stands out, engraved in his mind. In time, he embraced Bar Mitzvah prep, tutoring teens free, teaching them Torah portions and tefillin. Because of this, he was known as 'Grandpa Tefillin,' following him everywhere."

For Ben Savo, publishing 'Grandpa Moishele' was inevitable, sparking his fifth Holocaust book.

I must ask, since you said your books are for young ages, are you sure it's right to expose children to such difficult Holocaust depictions?

"I write stories appropriate for young ages to present the event, its meaning, and the ability to process it. My goal is to engage young generations with the Holocaust, a challenging yet crucial subject for preserving history."

Despite that, discussions of death marches, loss, and labor camps are hard to digest.

"Surprisingly, none of my books mention such terms. Someone remarked: 'Of all Holocaust books, yours is the friendliest I've read.' Even Rabbi Israel Meir Lau, a Holocaust survivor himself, said: 'My library is full of Holocaust books, but yours holds a special place for speaking to the young generation who might someday lack knowledge or interest.'"

In conclusion, Ben Savo notes: "As my name hints, my parents weren't born in Warsaw or Berdychiv. They're not Holocaust survivors but from the esteemed Moroccan-Spanish immigration. Yet, my heart is drawn to these Holocaust tales with a special place in my library. Each story documented feels like a unique journey.

"Moshe Porat is now 88 and a half. May Hashem grant him longevity with joy and grace, but in time, some won't know him. I hope even those future generations will learn of this character, understanding it's no myth or fable. Thus, I wish to immortalize him and my other story heroes, shaping our identity."