"They Opened Our Synagogues, But It's Just a Sad Joke"

The reopening of synagogues with a limit of only ten people is, according to Eli Ben Harush, Chairman of the 'Synagogue Association', nothing more than a sad joke. "What, do we leave the 11th worshiper outside the door?" he asks, revealing further difficulties faced by the synagogues, with some remaining closed indefinitely.

(Photo: Yaakov Cohen)

(Photo: Yaakov Cohen)"The caretakers of synagogues in Israel are experiencing the worst possible scenario," Eli Ben Harush begins our conversation, his voice filled with poignant sorrow.

Ben Harush, who leads the 'Synagogue Association', witnesses the current synagogue situations firsthand, attesting to their dire state. "They say there is no joy like resolving doubt," he says, "so we can understand that the worst situation is uncertainty. Unfortunately, this is exactly what the caretakers and worshipers are going through lately.

"Many synagogues across the country, which have successfully fostered communities and built unifying social fabrics over the years, were dismantled by the coronavirus. This led to closures, leaving these caretakers in a horrific state of uncertainty about their future. They have no outlook or estimate on when they can fully reopen and rebuild."

(Photo: Yaakov Cohen)

(Photo: Yaakov Cohen)However, this week, the Corona Cabinet approved reopening the synagogues.

"Approved?" Ben Harush's painful tone persists. "Saying there's approval to open synagogues is no more than a sad joke. What the government is allowing is opening each synagogue to only ten worshipers. What should a caretaker do with these restrictions? Should he stand at the door, counting people, and stop after the tenth? What if someone must urgently leave? Would they lack a *minyan*? Imagine a scenario where a veteran worshiper can't enter because he's the eleventh. The whole situation is absurd. I know some synagogues didn't open at all this week for this reason.

"Furthermore, one must understand that as long as synagogues aren't open, prayers continue outdoors. This week, as rains started, most street *minyans* became creative, essentially turning into something like the original synagogues, so we gained nothing."

(Photo: Yaakov Cohen)

(Photo: Yaakov Cohen)"Synagogues in Great Distress"

Ben Harush founded the Synagogue Association around eleven years ago, aiming to centralize caretakers. "We wanted to transition caretakers from being merely service providers to community anchors," he explains. "A smart person knows that a caretaker is the community's central figure, yet for some reason, they've never received due status."

Back then, Ben Harush himself was a synagogue caretaker in Elad. "I took the role after years in advertising, marketing, and publishing. Though I'd worked with many newspapers and entities, once a caretaker, I realized I lacked tools for even the simplest tasks. I saw a dire need for a body offering concentrated information on dealing with authorities, understanding the rights and duties of synagogues, and more. This preceded the creation of the 'Synagogue Association'.

(Photo: Azriel Moshe)

(Photo: Azriel Moshe)At that time, like everyone else, he never imagined a day when Israeli synagogues would close. "During the coronavirus era, when the synagogues closed, I witnessed very touching scenes," he notes. "I was mostly impressed by the mutual responsibility among people. Many small *minyans* were established, each with Torah scrolls, *siddurs*, and chairs, thanks to major synagogues generously sharing their resources. It was heartwarming to see the absence of divisions. Previously unimaginable, people from different sects attended *minyans* with others, especially during the coronavirus period. There were mourners who needed to recite *Kaddish* or lead, and neighbors went out of their way to organize street *minyans*, or even respond "Amen" from their balconies. It was deeply moving."

A closed synagogue (Photo: shutterstock)

A closed synagogue (Photo: shutterstock)Yet, Ben Harush notes an issue with open-air *minyans*. "Some people prayed at a fixed *minyan* for many years, but suddenly an alternative emerged closer to their homes. Though it's outdoors and less comfortable, some street *minyans* have become permanent, with structured settings that don't lack anything. They even hold Torah lessons, *Tehillim* groups, and outreach activities around the clock. Naturally, people might opt not to return to their regular synagogues, potentially damaging synagogues now on the verge of collapsing.

"It's like a synagogue in an area undergoing 'clearance-reconstruction'. It's dismantled for a good purpose—to eventually build a bigger, newer structure, but by then, the community might disperse, and there might be no one left to attend."

How did caretakers handle this entire long period?

"Caretakers aren't bored," Ben Harush assures. "Throughout the months synagogues were inactive, they maintained the place—ensuring cleanliness and maintenance—and ensured unauthorized access didn't occur, dealing with authorities simultaneously. In addition, most caretakers joined a street *minyan*, so they essentially managed another *minyan* simultaneously."

(Photo: Azriel Moshe)

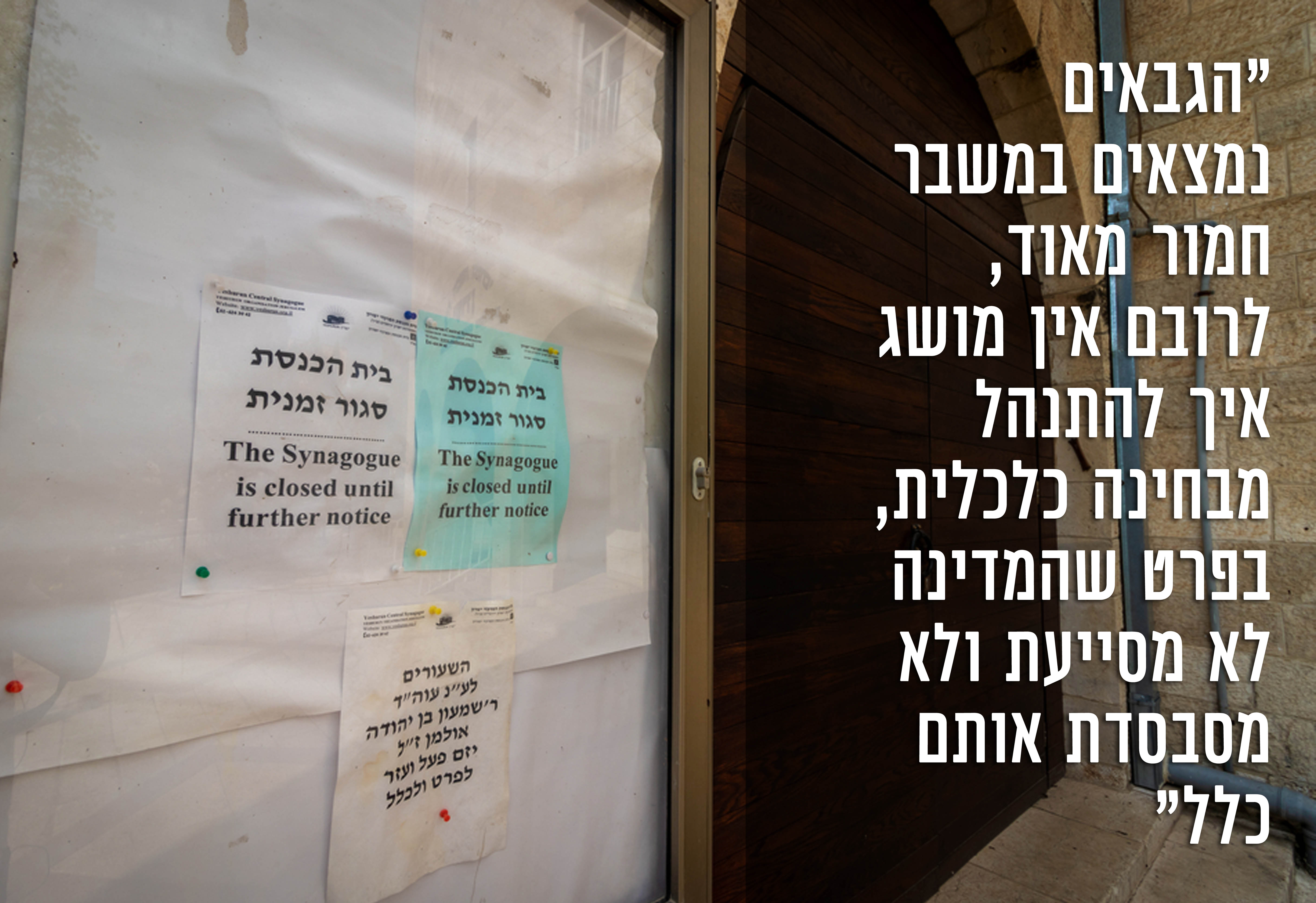

(Photo: Azriel Moshe)However, the real work for caretakers these days is fund-raising. "Synagogues are in severe distress," Ben Harush explains. "Though perhaps not well-known, synagogues depend solely on donations and people's generosity. Most donations come during the High Holidays. Unfortunately, this year's holidays were experienced in capsules and outside synagogues, with almost zero donations. Caretakers face severe crises, clueless about economic management without state aid or subsidies. Some may not reopen, even if allowed by the state."

Should there have been a directive opening synagogues to more worshipers?

"I believe there could've been plans to allow reasonable synagogue attendance, perhaps using capsules," he cautiously suggests. "From the previous lockdown exit, when calls to reopen synagogues arose, we didn't join them. We understood rabbis' views deeming it life-threatening and didn't want to risk it. But now, things are different. If synagogues are opening, they should at least provide a real solution."

Based on your knowledge of worshipers, do you think they'd fully comply with guidelines and measures?

"Definitely. The public I'm exposed to is very disciplined. Health and the divine directive of 'You shall preserve your lives' are very important to them. Everywhere I go, I see people strictly adhering to masks and social distancing. Those who don't are marginalized. I'm sure once synagogues reopen, the public will be very disciplined because health matters to them. But I stress that if the government allows opening, it should stick to the rules and not change plans constantly, as fitting synagogues takes substantial time and money."

In any case, even after synagogues reopen, Ben Harush admits a lingering fear. "We're definitely afraid of returning to locked synagogues. But I must point out the positive angle—we're seeing growing awareness and respect for synagogue sanctity, avoiding conversations during prayer, etc. The general synagogue perception has shifted—when a Jew who prayed thrice daily at a synagogue once took it for granted, now there's a longing for it. Suddenly, there's recognition of the great privilege—to simply enter a synagogue and pray."