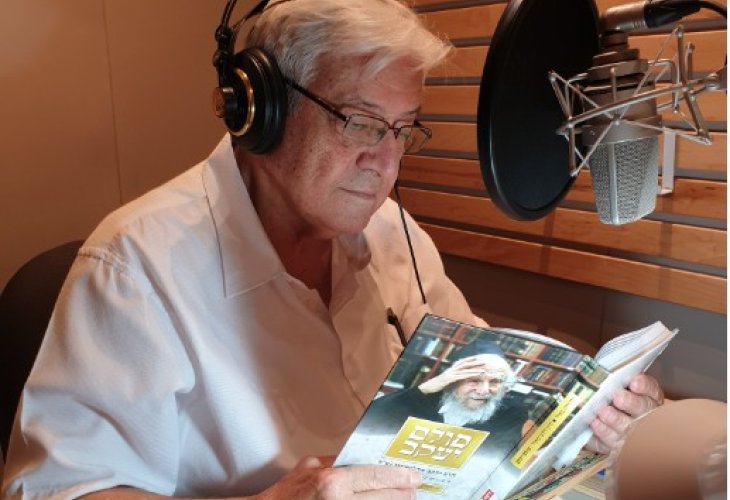

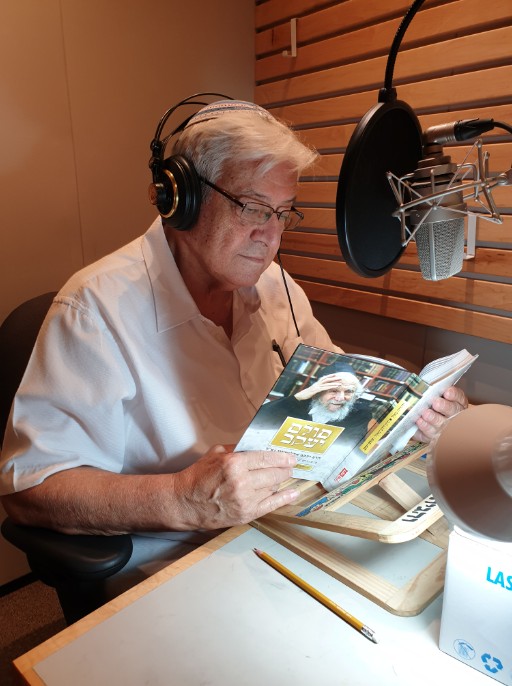

The Jewish Books Narrator: "I Am Moved That Thanks to Me, the Blind Can Pray and Learn"

Tzvi Florental is responsible for recording holy books at the library for the blind in Israel. In an enlightening conversation, he shares about the books he records and how he chooses them, the special requests from the blind, and the unique conversations he hears. "It literally brings people from darkness to light."

Tzvi Florental

Tzvi FlorentalIf a few decades ago you asked Tzvi Florental, then a radio and television announcer, if he knew the book "Guide for the Perplexed" by the Rambam, it's doubtful he would know what it was about. Names of rabbis like Rabbi Zamir Cohen, Rabbi Yitzchak Fanger, and others wouldn't mean much to him either. He never imagined that one day he would be in charge of recording holy books for the library for the blind, a task that would expose him to a vast number of sacred texts and profound thinking, revealing them to the blind public in Israel.

So how did he end up in this role? The story is nothing short of fascinating. "My wife is a judge," Florental shares, "and during the 80s, she sent people to do community service at the library for the blind in Netanya. Their main job was to roll the reels in 'tapes', as they were called then. These were tapes where various books made accessible to the blind by the library were recorded. Over time, the wires became tangled, and they needed fixing. It was a complicated process and quite intricate, but it was our first encounter with this field."

At that time, Florental worked in radio and television and was mainly known to the public from his regular program on Saturday nights. "My wife told me several times about the library for the blind, and one day when we were discussing it further, she said something very true: 'Charity starts at home'. By that, she hinted that if I wanted to do something good in life, I should volunteer at the library for the blind and narrate some of the books accessible to the blind public in Israel."

Hundreds of Hours of Torah

Florental thus began volunteering to record books in the library. Initially, it was once a week for a few hours. "I would come at night, after a full day of work, and start narrating. It was a chance for me to relax, a kind of unwinding and peace."

Later, he came two or even three times a week, and today, as a retiree, it is his main occupation. Over the years, his acquaintance with the library became very close, and he also understood its great importance as an organization operating for about 70 years to make culture and information accessible to the blind public in Israel. In the field of reading, the library produces books, textbooks, newspapers, and magazines in various formats, with no less than 12,000 subscribers.

About eight years ago, a new CEO named Amos Bar, blind from birth who studied at the HaMilpach school, earned a degree at the university, and joined the Israeli Police, where he finished as a deputy chief superintendent, joined the library. Immediately upon entering his role, he called Florental and asked about the state of the holy books in the library. "I told him the truth," Florental recalls, "'It’s bad', and in other words: 'They don't really give it much weight'. Bar asked me: 'Take it upon yourself', and since then this area has been under my responsibility. I dedicate all my time to this and employ narrators who narrate hundreds of hours a month."

In fact, he is in charge of the religious department for religious and Jewish topics, with hundreds of books recorded in a special studio established at the Blind Education Institute in Jerusalem.

What does your work entail as someone who oversees the field of holy books?

"I first and foremost need to find suitable narrators to record Jewish books. We have special studios, among the most advanced in the world, where we record the narrators. Of course, each narrator receives the book from us before he begins narrating and must prepare well in advance. It is essential that his voice is clear and his Hebrew impeccable. He must know how to read correctly in terms of punctuation, accentuation, and so forth. Of course, not all books are punctuated, so familiarity with Hebrew must be perfect. Once the narrator has finished recording, I send the recording for editing, where someone ensures that the narrator did not skip words or bypass lines and also 'cleans' the recording. Because we're dealing with the blind, we must remember that they don't see the text and might understand it mistakenly. For example, if I read the word 'haroeh'. They can’t know if I meant 'seer' or 'shepherd'. Personally, I solve this by indicating during the flow of the reading whether the word is written with an aleph or an ayin, a bet or a vav, and so forth."

(Photo: shutterstock)

(Photo: shutterstock)Do you also narrate some of the books yourself?

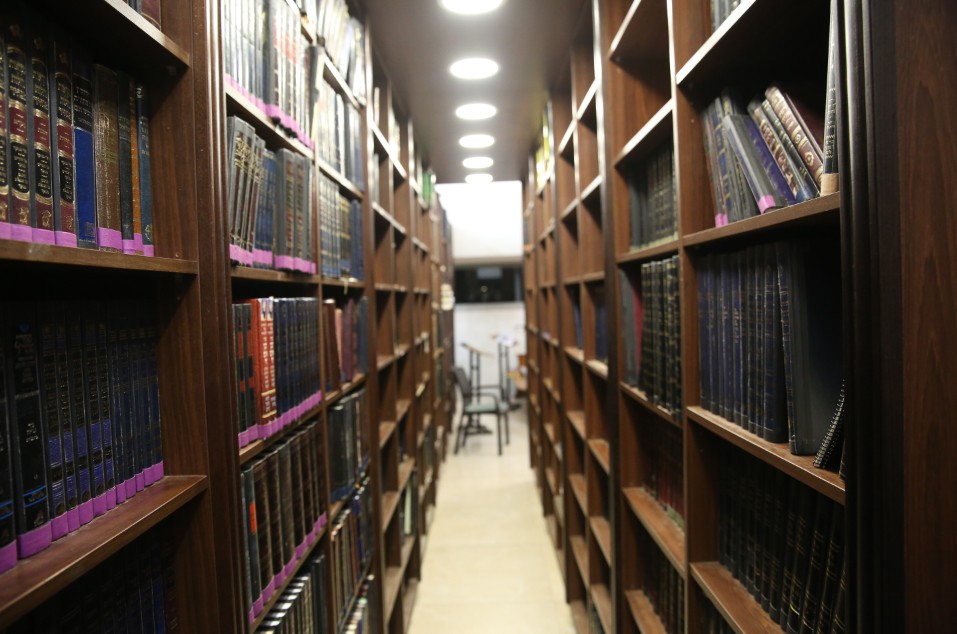

"Of course. Over the years, I have narrated thousands of books, with recent years focusing naturally on holy books such as Tanach, Siddur, 'Guide for the Perplexed' by the Rambam, alongside philosophical and thought books, as well as books written by people of the last generation, like 'Sulam Yaakov' about Rabbi Yaakov Edelstein z"l or 'Toolbox' by Rabbi Fanger. We have a very large selection, although it is still not enough. Currently, there are more than 24,000 Jewish books on the market. We are far from that, and since the library was established, we have managed to record about 700 books in this field."

How do you decide which books to record?

"Sometimes it happens following requests from subscribers. They contact us and ask to record a particular book for them, and we strive to comply, even if in terms of ratings we are not sure the book will 'run'. Additionally, I sometimes consult with friends and narrators from various sectors. I try to provide representation for all audiences and segments within the observant public to tailor the content to everyone. Of course, we also keep an interest in bestsellers and new books that come out and give them priority."

Is there a book that particularly interested you or that you greatly enjoyed narrating?

Florental finds it difficult to pinpoint a specific book, but he refers to a few special projects in which he invested all his energy and effort. "It was very important for us to record the Six Orders of the Mishnah with Kehati's commentary. To this end, I started a project that lasted about two years, during which I brought into the studio three yeshiva students recruited especially for this purpose. At first, there was a debate whether to ask them to read the Mishnah in the holy language or in a particular inflection. Ultimately, we decided to record them in modern Hebrew. The result is 400 hours of the Six Orders of the Mishnah—one of the most important things for a blind person wanting to learn. Additionally, there's a project to record prayer books in various traditions, which was also critically important."

So you have had the opportunity to accumulate many hours of Torah study...

"Unfortunately, I don't define it as study. True, I narrate, but I understand things according to my intellect, and I must admit there is room for improvement in this comprehension. What I can say clearly is that the recordings were undoubtedly made correctly and appropriately, in the most precise manner we could accomplish."

As he speaks, he also recalls a particularly moving case: "One day, while waiting near the counter in one of the hospital departments, when my turn came, I opened my mouth to ask the question I wanted to ask. Suddenly, the man beside me turned towards me and said, 'Hello, Tzvi'. I replied, 'Hello to you as well. Do we know each other?' To my surprise, he answered, 'I know you well; we pray together every morning'. At first, I didn't understand his words, but he continued and said, 'You can't see it on me, but I am blind'. Only then did I realize. It turned out that he prays every day with the Rinat Yisrael siddur that I had recorded about a year earlier. I must say it moved me enormously. I never know where the books I record reach, but I believe each recording reaches the places where it's most needed."

(Photo: shutterstock)

(Photo: shutterstock)Recorded Conversations

Are there people who aren't blind but wish to use the recorded books? Is that possible for them?

"Unfortunately, the answer is negative," Florental replies. "The reason we record the books is by virtue of a law enacted in the Knesset in 2014 that allows for the accessibility of recorded books to people with disabilities. At the beginning of each recording, we declare that the book was recorded by virtue of this law, and it is prohibited to use or infringe upon its copyright. In other words: only library subscribers who have visual impairments are permitted to read it and have no permission to pass it on."

And what about people with dyslexia, for example? Are they allowed to use the recorded books?

"Indeed, as far as we are concerned, people with dyslexia are considered visually impaired, and the books are intended for them as well. Not everyone knows, but today we have reached a situation where one in four children is defined as dyslexic at some level. This means that at the beginning of each school year, we receive many requests from parents who want to record textbooks for their children. This is our top priority, as we are aware of the great need."

Incidentally, speaking of children, Florental notes that a few years ago, he embarked on an interesting initiative. "As I mentioned—we currently record within the Blind Education Institute in Jerusalem and are in constant interaction with blind children. On the eve of Rosh Hashanah, I noticed all the 'regular' children returning home from kindergarten bringing with them drawings of a good year for mom and dad, for grandparents, attaching them to the refrigerator and receiving so much attention. What about blind children, who can't draw and write? At that moment, a special idea came to my mind—I invited the children to the studio and recorded each one individually while they wished a good year. They received these greetings burned onto a CD, and that's what the parents finally heard at home. It was so amazing and moving."

Another interesting area Florental mentions they deal with is the recording of newspapers and Shabbat leaflets, including Hidabroot leaflet. "Every Motzei Shabbat, I sit to record myself as I narrate all the bulletins and newspapers, and finally produce a file with several hours of reading. By Monday, the file is uploaded to our site, with many subscribers listening to it. I see a genuine interest, especially among those who weren't born blind, and for years were used to reading the bulletins or papers. Sometimes these are older people who have gone blind, and they miss flipping through newspapers and booklets so much.

(Photo: shutterstock)

(Photo: shutterstock)"Just recently," he recalls, "an elderly woman contacted me, sharing how much she enjoys listening to that special file. When I asked her what interested her the most, she replied that it was the 'Daily Page for Children'. "And understand," Florental becomes emotional, "it's a woman far removed from keeping mitzvot. There's no chance she would have been exposed to these contents otherwise. Incidentally, the woman contacted us afterward, requesting more holy books to be recorded for her. It turned out she was really strengthening and progressing.

"You know the recording that tells you on the phone line, 'Please be aware, some calls may be recorded'?" he asks playfully, "Sometimes after I chat with subscribers and hear how they study Torah thanks to the books we recorded, delve into ethics and halacha, I look to the heavens and say—'Master of the world, I hope you recorded this conversation, and it will be kept for me in times to come.'"