The Rabbi of the Ethiopian Community in Netanya: "Our Children Are Not Being Accepted into Schools, Isn't it a Shame?"

Rabbi Avraham Inbaram of the Ethiopian Community in Netanya was one of the early immigrants from Ethiopia. In a captivating conversation, he shares the customs of Ethiopia, the traditions they hold, and his decision to become a rabbi despite all the challenges.

Rabbi Avraham Inbaram

Rabbi Avraham InbaramWhen Rabbi Avraham Inbaram arrived in Israel in 1981 after various travels through countries in Africa, he was quite surprised.

"We thought that here people better observe the commandments and Jewish traditions," he says. "But suddenly, we were welcomed by secular Jews. We couldn't believe such things existed. It was very hard to see and believe that a Jew would desecrate Shabbat, especially in the land of Israel." The pain is evident on his face.

What was it like in Ethiopia?

"The health situation in Ethiopia was very tough. I can talk about my family personally - we were ten siblings and six of them passed away. Only three brothers and a sister remained. I only knew two of the siblings who died. My father took it very hard but he didn't lose his spirit and broke down. He decided to marry another woman to restore for himself and us the souls that were lost to the people of Israel."

Is it allowed to marry another woman in Ethiopia?

"Yes, Jews in Ethiopia did not accept the ban of Rabbeinu Gershom which prohibits a man from marrying two women. In general, in Ethiopia, there are different customs and laws entirely from what we knew in the land of Israel."

Unrecognized Laws

The conversation with Rabbi Inbaram is fascinating and continuously reveals more details about the life of Judaism in Ethiopia. It turns out that the Jewish communities in Ethiopia lived isolated from other Jewish diasporas, and because of this, some of their customs differ from rabbinical Judaism, that is, Jews who follow the oral law learned from the Mishnah and Talmud. Famed decisors like the Rif, the Rosh, the Tur, and the Beit Yosef who compiled the Shulchan Aruch, which is the most recognized and accepted code of law in Jewish communities everywhere, were unknown there.

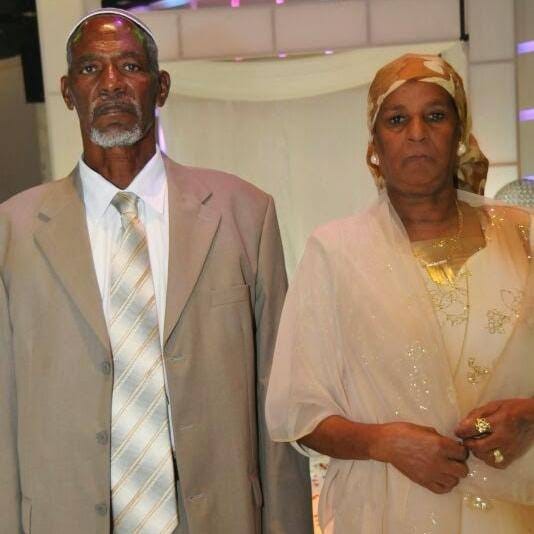

Rabbi Inbaram and his wife

Rabbi Inbaram and his wifeIf in Ethiopia they didn’t follow the Shulchan Aruch, then which laws were followed there?

"In Ethiopia, the Shulchan Aruch was unknown. The local sages were not familiar with the decisors recognized in Israel and the diaspora. All our laws and customs were written on community parchment. Each person noted the traditions remembered from their parents' home, the laws observed on Shabbat or in ritual slaughter. These were documented, much like during the time of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, who systematized the Mishnah by collecting sayings from the Tannaim. Similarly, in Ethiopia, our own Shulchan Aruch was built on the oral transmission of customs."

What different customs did you discover in Israel?

"Almost everything was different. For example, we didn’t have the same wedding canopy as is customary now; the groom didn't break a glass, our seclusion ceremony was far more serious than what is done here, and the marriage contract was entirely different. Our holiday customs also varied, for instance, on Rosh Hashanah no shofar was blown as a reminder of the lack of shofars and the ritual, so instead, people beat drums and clashed cymbals. In holiday prayers, the binding of Isaac and blowing of the shofar were remembered. Shabbat was celebrated differently due to the biblical prohibition of lighting a fire, so coals were extinguished and smothered in water before Shabbat to ensure no fire was burning on the day."

One Torah for All

What was identical to what you saw in Israel?

"The only thing that was identical were the Torah scrolls, they are exactly the same as the scrolls in Israel and the rest of the diaspora. This is due to the Jewish tradition kept meticulously in Ethiopia for two thousand years."

It is known that there are varying opinions regarding the history of Ethiopian Jewry. There is the popular tradition that Ethiopian Jews are descendants of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, and others suggest that after the destruction of the first Temple, exiles went down through Egypt to Ethiopia, from Judah or Dan Tribe. Some believe they are descendants of a group that split from the Dan Tribe and migrated southwards along the Nile and settled around Lake Tana. Rabbi Inbaram, what is known to you about this topic?

"I know there are several opinions on this topic, but according to what I know, after the destruction of the First Temple, they arrived in Ethiopia, and when the Second Temple was built, Ezra brought back the Tribes to Israel, but Ethiopian Jews did not come and remained there, thus maintaining our ancient tradition."

This is Rabbi Inbaram's father-in-law

This is Rabbi Inbaram's father-in-lawHow did you and your family come to Israel?

"We walked from Ethiopia to Sudan, a group of about 300 men, women, and children, with all our grandparents. The journey's hardships were horrific, we were robbed and left with nothing, much like Jacob after being robbed by Eliphaz, the son of Esau. Later, we understood that it was a pre-arranged plan between the robbers and our guides. The method was to instruct us to drop leaves on our paths so that those who got lost could find their way back to the group. But in reality, it was a trick to mark the way for the robbers. Thus, we were robbed many times; not that there was much left to rob after the first time, yet even the little that remained was taken ruthlessly."

For how long did you walk from Ethiopia to Sudan?

"We walked for two months, then arrived in Sudan beaten and bruised. Many among us died from an epidemic that spread, but we persisted in our faith and desire to see the holy land. We stayed in Sudan for more than a year until we were transported by ships to Israel, landing in Eilat, and then flown to Tel Aviv."

What did you discover upon arriving in Israel?

"Those who welcomed us in Israel were Jews, but they were secular. We were shocked by the concept of a secular Jew because in Ethiopia, anyone who didn’t properly observe the religion was considered a foreigner, behaving like a Christian, and couldn’t claim Jewish identity. It was very difficult to understand."

"I Worked and Thought about Torah"

What did you do upon arriving in Israel?

"I really wanted to learn Torah and asked those in charge of the group: 'How can I study Torah? I want to be ordained.' I explained I used to study Torah all day in Ethiopia; they told me that here in Israel, it’s different. Anyone wishing to earn a living must work rather than study Torah."

So, did you stop studying Torah and started working?

"I had no privilege to object or act differently from what we were directed, so all our families were settled in Pardes Hanna and I started working at Carmel Carpets in Or Akiva. Adjusting was difficult; I sought a synagogue for prayer initially at the Georgian synagogue, but Georgian and Ethiopian sounded like the start of a joke, so I couldn't manage with their prayer customs, leading me to wander from community to community until I found the Moroccan synagogue, where I connected more with the melodies of prayer."

How did you become the Rabbi of the Ethiopians in Netanya from Carmel Carpets?

"Big things don’t happen all of a sudden; in my heart, I felt a deep void driving me constantly towards Torah study until I met Rabbi Yosef Hadana, the chief rabbi of the Ethiopian community. During a visit to our small community in Pardes Hanna, I told him, 'Rabbi, my soul desires Torah; I want to study Torah.' The rabbi was moved by my wish and introduced me to Rabbi David Shlush, the chief rabbi of Netanya. Rabbi Shlush told me to find ten Ethiopian youths who wanted to study Torah, and he would arrange suitable lessons for us."

Did you quit work and start learning Torah?

"Not immediately, unfortunately, I didn’t manage to get ten youths. Every young man I asked to join the class said, 'Those who learn Torah stay poor; in Israel, Torah isn’t necessary.' This echoed the chorus they heard from those in charge. Despite not giving up, only six agreed to study, my dreams vanished, and the class didn’t open."

The extended family

The extended familyYou didn’t leave the job, and the class didn’t open, yet today you are a prominent rabbi. How did that happen?

"After failing to recruit ten young men, I felt broken. I decided not to stay in Pardes Hanna anymore; two and a half years of spiritual desolation were enough. Our group dispersed across the country, meaning that sadly, some changed their lifestyle. I moved to Netanya to be closer to Rabbi Shlush and benefit from the holy Torah, where I resumed Torah study. After moving to Netanya, Rabbi Yosef Hadana recommended a Yeshiva in Mevaseret Zion that might suit me. I enrolled and started learning there."

Did you move to Mevaseret Zion?

"I didn’t move; I stayed in Netanya, traveled to Yeshiva on Sunday, and returned home on Thursday. By then, I was already married and had two children, but the desire to learn Torah was so intense that I gave up worldly pleasures for the afterlife. My righteous wife supported me throughout. She had been raised with good traits and understood the value of Torah I explained to her. She wanted this very much. Later, we had ten more children, making fourteen of us in total. Despite everyone persuading us not to have a lot of children, saying three or four are enough, some bought into it, but my wife and I did not."

How long did you study in Mevaseret Zion?

"After a year, I completed studies in Mevaseret Zion, but instead of returning to Netanya, I went to the Meir Institute in Jerusalem. The Yeshiva was eager to have us Ethiopians join, offering a special Torah study program. I studied there for 10 years, being away all week and returning only on weekends. It was not easy—in fact, it was quite hard, but today I can say it was very rewarding.

"After three years, we were told at the Yeshiva to qualify for rabbinates. The late Rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu encouraged and pushed us to get rabbinic ordination. Additionally, I learned ritual slaughter, which sadly revealed the improper slaughter practices in Ethiopia. After completing my studies, I received Yoreh Yoreh certification and others for ritual slaughter, carving, weddings, and ordinations. I returned to Netanya and began serving as a rabbi in the religious council, advancing gradually."

What message would you like to convey to the Ethiopian community and the people of Israel?

"I want to tell everyone, especially Ethiopian youth, that Torah builds a person and their character. Those who abandon Torah and the Creator cannot be said to truly live. Anyone thinking they can desecrate Shabbat and prosper—it’s all nonsense. The best path is staying close to the Creator."

Discrimination is Hard, Sad, and Unnecessary

It’s impossible to ignore discrimination against Ethiopians. What are your thoughts on this matter?

"I think anyone familiar with our people knows there are no better people than Ethiopians worldwide, marvelous, respectful, and humble. But we're relatively new in the country, and generally, it’s hard for people to accept strangers. Even in Ethiopia, if strangers came to our village, they wouldn’t be easily accepted, remaining odd to us despite being Jewish."

Where does discrimination affect you in daily life?

"We encounter it in institutions, our children and girls aren’t admitted to educational institutions, it’s a real shame because parents want their children to grow as proper Jews. When not accepted, they stray into foreign fields; isn’t it a waste for these souls? The late Rabbi Ovadia Yosef would always say in his Saturday night lessons: 'Ethiopians are our brothers, we must draw them closer,' regrettably, that did not happen, and it’s a pity."

What is the current state of the community’s Judaism?

"Thank Hashem, our youths in the neighborhood all go to Yeshivas, each to a suitable Yeshiva, but all are strong and righteous servants of Hashem. Our synagogue ‘Siman Tov’ in veteran’s neighborhood, Netanya, is filled with worshipers desiring just one thing, to do our Father in Heaven’s will. And remember, a father loves all his children."

What about the dropout issue in the community? Do you think it is more prevalent than in other sectors?

"I have no metrics to gauge this, but what I observe is a broader trend of our children studying less and idling more. Only those who haven’t abandoned Torah’s path manage to preserve themselves, even if they don’t study Torah all day, but observe commandments—it’s important, and their dropout rates are significantly lower. However, amidst this all, it's crucial to remember we have no atheists denying the Creator, all believe there is a Creator, some find it harder than others, but all strive to be good."