"I Was Admitted to a Mental Hospital": Rabbi Yosef Mendelevich on His Years as a Prisoner of Zion

He grew up in Soviet Russia but gradually discovered Judaism and began to embrace it. To draw the world's attention to the plight of Soviet Jews, he planned with his friends to hijack a plane, but the plan was uncovered, and they were caught. Rabbi Yosef Mendelevich talks about his journey, the secret operation, and observing mitzvot in prison.

Rabbi Yosef Mendelevich

Rabbi Yosef MendelevichRabbi Yosef Mendelevich grew up in communist Russia, where despite having no knowledge of Judaism, the Jewish spark within him began to ignite, yearning for a different way of life. In 1970, at the age of 23, he and his friends planned to hijack a plane and fly from Russia to Sweden. The cover story was a flight to a large family wedding. The continuation of the plan was to hold a major press conference to voice the plight of imprisoned Russian Jewry and galvanize the world to act for them. Unfortunately, the KGB discovered the plan, and they were caught and charged with treason. Rabbi Yosef was sentenced to 15 years in prison, of which he served 11, three of those under severe conditions. His fascinating story has been published in three books: "Operation Wedding" and "Free Man" about his life story, imprisonment, and release, and the book "From the Ends of the Heavens" about observing mitzvot in the Soviet prison. Despite everything he went through, he doesn't regret it for a moment: "We were blessed that our way opened the gates of aliyah to Israel."

Release Day at Ben Gurion Airport

Release Day at Ben Gurion AirportJewish Sparks in Communist Russia

Rabbi Yosef was born in 1947 in Riga, Latvia, in a communist home where mitzvot were not observed. As a child, his father had studied in a *cheder*, but he left the path of the Torah in favor of communist values, which he saw as true justice in the world. "At home, we spoke Latvian and Russian, and also Yiddish, which my father retained from his childhood," he recalls. "Interestingly, my father even taught me the Hebrew alphabet, but beyond that, we grew up understanding that there is no Hashem and that religion has no place in the world."

Rabbi Mendelevich's initial encounter with Judaism came ironically through the non-Jewish society around him. "One day, the school teacher decided to ask each student about their ethnicity. When she got to me, I intended to say I didn't know. But then I remembered my father, who looked Jewish, and I felt I couldn't deny him, so the truth about my Jewishness came out of my mouth. As I had anticipated, the children's reaction to this revelation was far from pleasant—they started cursing me and calling me derogatory names, and I ran home quickly. As children do, the next day it was all forgotten, but the question still lingered in my mind—why do they hate us? How are we different from any other nation?"

Rabbi Mendelevich performing Havdalah

Rabbi Mendelevich performing HavdalahAnother Jewish spark arose when he was ten during his father's trial following an unexpected arrest. "Father was arrested without reason, as part of the oppressive communist regime's practice of instilling fear instead of helping people develop. Several months later, his trial took place, but we were not allowed inside the court. My mother, my sisters, and I stood outside in freezing cold and snow to hear the sentence."

Rabbi with his family at age 10

Rabbi with his family at age 10In those moments, a prayer arose in young Yosef's heart. "I didn't know who I was speaking to, but I asked them to help my father and promised to be a good boy and do what I'm told. Then I fell silent because I didn't understand what I was doing, but in those moments, I felt that Hashem existed, despite having been raised all these years to believe otherwise."

A year later, Yosef encountered Jewish words for the first time in his life. "At eleven, when my mother passed away, I heard the Kaddish for the first time at the cemetery. I understood nothing of it, but I felt that these special words lifted me up. The very sound of them made an impression on my soul. I told myself that the day would come when I would understand this prayer, and I would also be able to say it."

Due to a dire financial situation, Yosef began contributing to the household at age 16, working in a factory during the mornings and attending school in the evenings. "In the evening classes, I discovered almost everyone was Jewish, and one day, a friend said we wouldn't be studying today because it was Rosh Hashanah. He explained that for Jews, the year starts at a different time than for Russians. At the time, being part of the Jewish people was difficult for me because Judaism seemed so different, classifying us as second-class citizens. That friend said we should go to the 'singaoga'—synagogue—on Rosh Hashanah, and I wondered what we, learned people, had to do with such an outdated place. Still, I went just to be with my friends, and it turned out quite pleasant there. We didn't pray, but it was a meeting place for other youths, and I enjoyed it. I asked my friend when the next holiday would be, and he said in ten days. Indeed, we all met again at the synagogue and had a good time together. The next holiday was Sukkot, and I thought, 'How wonderful, a different holiday every week.' Today, I can say that by the grace of Hashem's divine supervision, I met Jews and came to that place, and even continued my visits, an opportunity not all my friends had."

One day, a friend announced that on the coming Sunday, a day without school, young people would come to help renovate the Jewish cemetery. "I was the only one from my class who decided to go," says the Rabbi, "unlike other friends who preferred going to the cinema, studying for exams, or simply enjoying the weekly day off. While we were there, we discovered this wasn't just any cemetery but a place where twenty-eight thousand Jews had been massacred in 1941. We began coming every Sunday, and over time, we formed a group that gradually learned about belonging to the people of Israel. On the memorial day for the victims, I told my friends that we came to help the deceased, but they actually helped us to connect and discover our Judaism. The very memory of Holocaust victims heightened our sense of responsibility to act for our people's restoration."

Driven by this, at 19, Rabbi Mendelevich and his friends founded a student organization aimed at saving the Jewish people from assimilation. "We didn't yet know mitzvot, but we understood that we were a different people. We began clandestinely studying Jewish history and learning Hebrew from a Hebrew-Russian phrasebook smuggled from the Israeli embassy by one of our friends. Meanwhile, a commitment grew within me to start observing mitzvot. I asked people in the local synagogue to teach me, but it was illegal, and they were afraid to do so. Only Mendel Gordin, a secret mohel, agreed to teach me a little. Over time, my desire to be Jewish, pray, and observe mitzvot intensified. Although considered a 'fanatic' among my friends—one who fasted on Yom Kippur and didn't eat chametz on Pesach—I had very little knowledge, yet a burning desire to learn more."

"In Prison, I Felt Like a Free Man"

In 1970, Yosef and his friends organized "Operation Wedding," but were caught by the KGB and accused of treason. "The day we arrived at the airport, we were all apprehended, and told that a death sentence awaited us. From the officers' demeanor, I realized they wanted to break our spirits, so we would cave and discourage Jews worldwide from intervening on our behalf," the Rabbi recounts. "Unlike some of my friends who broke, I wasn't willing to. Seeing my steadfastness, the Russians tried to break me by admitting me to a mental hospital, threatening me with forced treatment meant to drive me insane. I stayed there for a month, but even then, I didn't change my mind, so they had no choice but to alter their approach toward me. I was returned to the investigation room, where the interrogator tried convincing me to cooperate, promising I could later return to normal life."

At that point, Yosef did something seemingly irrational, but for him, it was the appropriate course of action. "I heard a kind of heavenly voice telling me that my path to overcoming all these troubles was not to surrender but to observe the Torah and mitzvot. This option put my life at risk, but it was the inner truth burning within me. I informed the investigator I wouldn't cooperate and began building a sort of wall between us," Rabbi Mendelevich shares. "Later, when I was confined to my prison cell, I took my handkerchief, tied four knots in it, and placed it on my head as a kippah. At the next interrogation, the examiner was very angry about it, but precisely because of this, he received a lengthy discussion about Judaism from me, even signing the interrogation protocol. Returning to my cell, I attempted to recall and recite passages of prayer, jotting down personal requests on a scrap of paper. I would stand in the cell and pray, and the investigators monitoring me tried to understand why I was always by the wall, stroking it. When they realized it was prayer, they sent me to a psychologist, who inquired who influenced me to do this. I said only Hashem influenced me, which of course angered him further."

Rabbi Yosef decided to also observe Shabbat, employing a particularly creative approach for it. "Keeping Shabbat in prison isn't difficult since there's nothing to do anyway, but it was important to me to honor Shabbat and prepare for it. Hence, I began collecting slices of bread throughout the week, ending up with six slices in honor of Shabbat. I tore my handkerchief in half—half I placed on my head, and the other half I used to cover the 'challahs.' I started cleaning my cell for Shabbat, and on the floor, I found a nail. I etched a drawing of Shabbat candles on the wall with that nail and told myself these were the candles I lit. I blessed over them, and when I lowered my hands from my face, I felt they were truly lit. In those moments, I was deeply moved. A person awaiting a death sentence, observing and honoring Shabbat within his small prison cell. Overwhelmed with emotion, I began singing and dancing 'Am Yisrael Chai' until the guards ordered me to maintain silence. Yet, I felt that even in darkness we could be Jewish and overcome the communist regime. The mitzvot made me a free man, even as walls and bars surrounded me."

The prison cell

The prison cellThe Soul Doesn't Give Up

The plane hijacking didn't succeed, but it made a huge impact globally, opening the gates for a wave of aliyah from Russia in the 1970s. "We didn't reach Sweden, but the press conference we planned was held in court," the Rabbi recounts. "I was imprisoned for 11 years, but knowing that I had the merit of redeeming tens of thousands of Jews fueled my joy in the path I chose. Even in prison, I constantly engaged in bringing friends closer to observing the Torah and mitzvot. We held Shabbats and holidays in less than ideal conditions, but we were elated at the privilege of being Jews. One friend told me he never had brighter days than those in prison. I thank Hashem for bringing me closer and choosing me for this mission, believing that any Jew can reach Hashem as I did, should they choose to."

Siberian labor camp

Siberian labor campSince then, Rabbi Mendelevich has been ordained as a rabbi, earned a master's degree in the history of the Jewish people, and now teaches in the Russian-speaking department of Machon Meir. "I had the immense privilege of coming closer to Hashem from a place where Judaism wasn’t acknowledged," he states. "In the communist Russia where I grew up, they told me nothing about the Torah or Hashem, and when people ask how I found Hashem, the answer is solely that Hashem brought me close. He provided me with trials and the strength to endure them, watching over me so I could come to know Him. Someone once told me that every Chassid has a Rebbe, and my Rebbe is Hashem, directly influencing me. When the Russian authorities noticed the emerging phenomenon of Jews becoming more observant, they were shocked, believing everyone was assimilated. But that’s the great miracle—the Jewish soul doesn’t give up, and even without knowing anything or any external assistance, it awakens on its own."

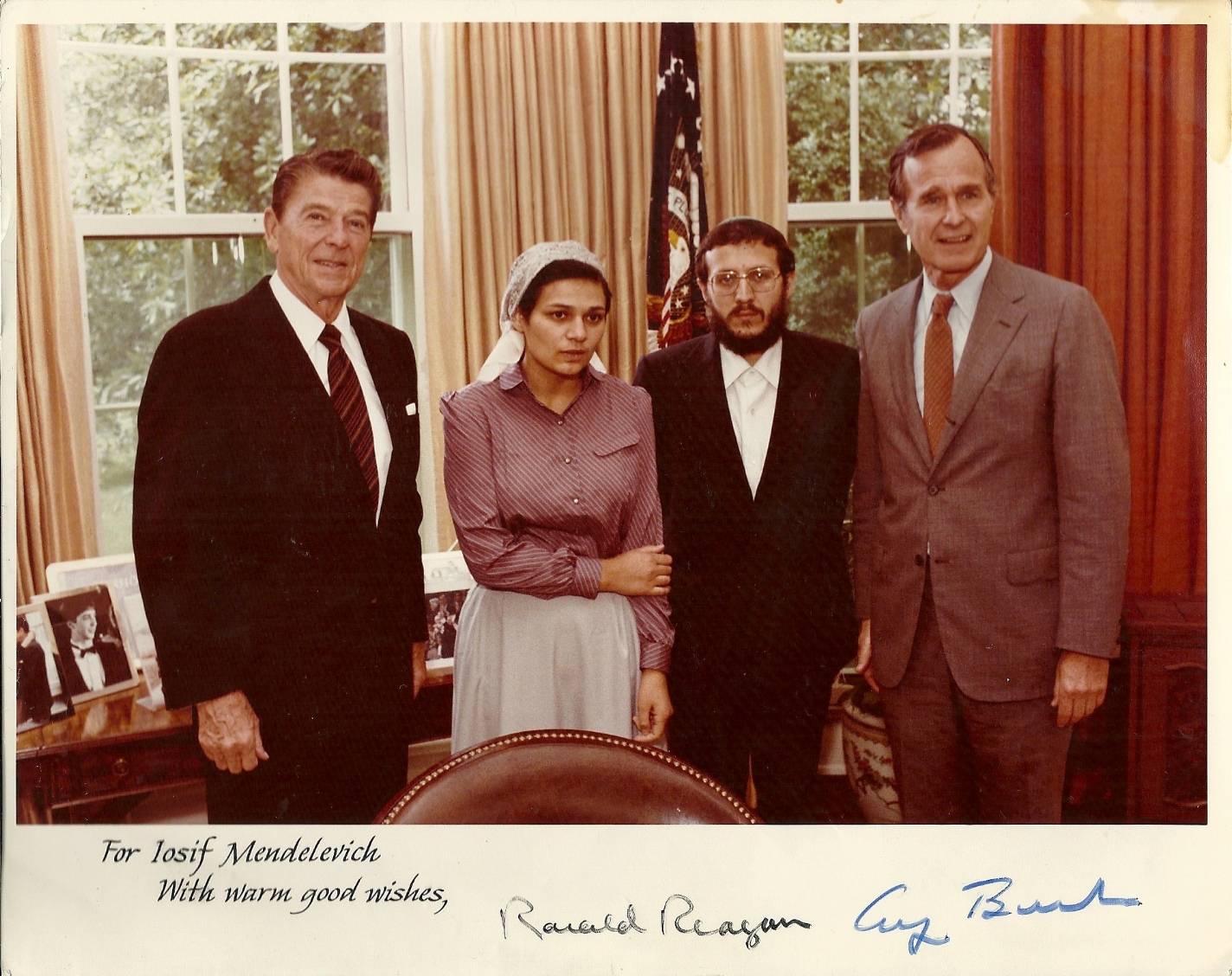

With President Reagan

With President Reagan