The Holocaust

A Childhood of Hunger and Hope: Holocaust Memories from Rome

From hiding in a convent to building a new life in Israel, one family’s courage and miracles

(Photo: shutterstock)

(Photo: shutterstock)When we think of the Holocaust, our minds usually go to the harrowing stories of Polish and German Jews who were sent to extermination camps. When speaking with Ilan Jacobi, a very different Holocaust story emerges. “I survived World War II, but not in Poland or Germany — rather in Italy,” he begins.

Escaping Germany Just in Time

“I was born to parents who fled Germany — Berlin, specifically, just before the borders closed in 1938,” recalls Jacobi. “At that time, it was still possible to cross. My parents traveled directly from Berlin to Rome.”

He explains that his grandmother was the driving force: “My wise grandmother declared to everyone that she was leaving, no matter what. She didn’t care that her siblings and in-laws insisted on staying in Germany. She said: ‘I am leaving with my husband, my daughter, and her husband.’ And so, they left everything behind and went to Rome with no possessions at all. That move saved our lives.”

Jacobi was born soon after they arrived. Growing up, he spoke German with his grandparents, Italian with the locals, picked up English and Hebrew later in life, and even learned Yiddish from his neighbors.

The Nazi Invasion of Rome

Until 1943, Italy was relatively calm. But on October 16, 1943, everything changed. “The Nazis came into the Roman ghetto and announced a massive roundup of Jews. That day I happened to be outside the ghetto with my mother and grandparents, which saved our lives. My father, however, was inside. He was deported to Auschwitz and murdered there.”

Realizing the danger, the family never returned to the ghetto. They escaped by train to a neighborhood outside Rome, where they were taken in by a convent. The nuns cared for them and even provided food ration cards. Ilan was only four and a half when he entered the convent kindergarten. One nun, knowing full well that he was Jewish, treated him with extraordinary kindness. Thanks to that convent, Ilan, his mother, and his grandparents survived — though they were the only survivors of their once-large extended family.

Grandson Claudio – Ilan Jacobi

Grandson Claudio – Ilan JacobiLiving With Hunger

Life in hiding was far from easy. “The main thing I remember is the hunger. Terrible, constant hunger. My grandmother discovered eucalyptus trees nearby. She suggested peeling the bark and boiling it in water to make something like soup. Every day she cooked this ‘eucalyptus soup,’ and every day my grandfather tasted it and said, ‘You know, my dear wife, today’s soup tastes even better than yesterday’s.’”

Ilan recalls begging his mother for bread. “I asked for a roll. She said: ‘There isn’t any.’ So I asked for half a roll, then a quarter of a roll. Later she told me it amazed her how a four-year-old had learned fractions — all thanks to a piece of bread.”

The starvation left him ill. He developed a condition resembling epilepsy, with fainting spells, convulsions, and swollen eyes. The illness haunted him for years, even after he immigrated to Israel.

(Photo: shutterstock)

(Photo: shutterstock)A Mother’s Bravery

Ilan’s mother, he emphasizes, was a true heroine. Working as a seamstress, she befriended a Christian woman named Marta, who risked her own life to help. Marta once smuggled Ilan’s mother into a Nazi officers’ gathering place, where she managed to obtain leftover food for the family — without the officers realizing they were sustaining hidden Jews.

Later, as the war neared its end, the Vatican moved the family from the convent to a small hiding apartment. Two suspicious sisters living there questioned their identity. Again, Marta intervened, forging documents proving they were Christian. Ilan’s mother trembled with fear when presenting them at the police station but managed to obtain the stamp. From then on, the sisters kept silent, and the family’s situation improved.

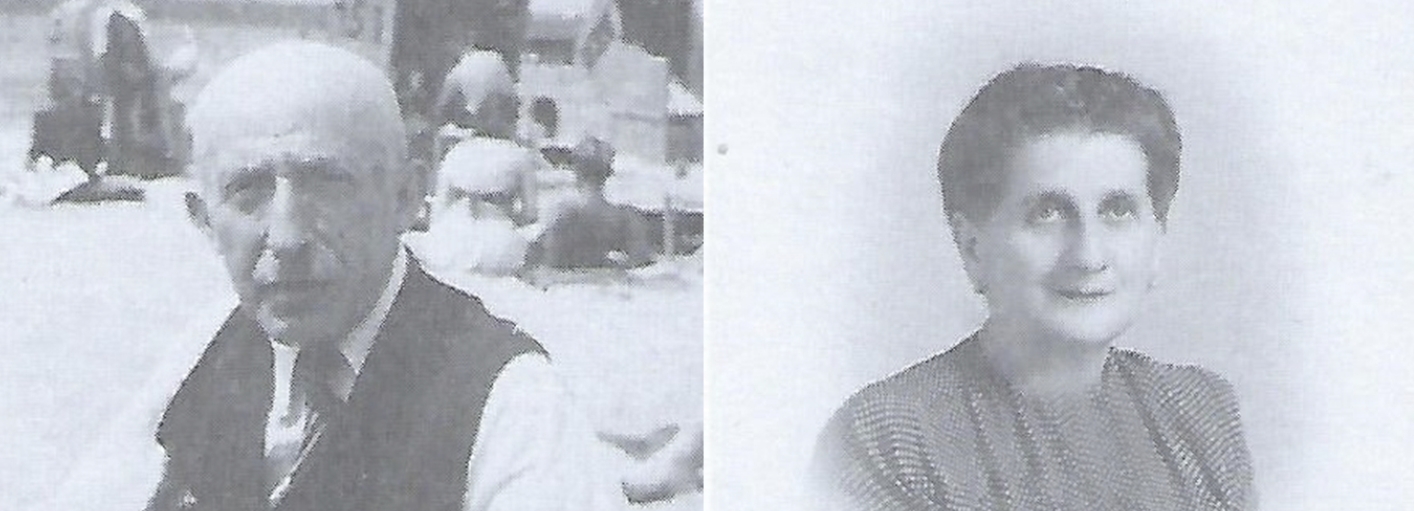

Grandmother Mina Jacobi and Grandfather Hugo Jacobi

Grandmother Mina Jacobi and Grandfather Hugo JacobiA Childhood Without Friends

Ilan recalls that he never had a normal childhood. “In the convent kindergarten, the other children always sensed I was different. We used a cover story that we were refugees from Switzerland — it sounded believable since we spoke German, but they kept their distance. I had no friends in Italy.”

After the war, one of his most emotional moments came at age seven: finally undergoing a brit milah (circumcision). “My mother had delayed it out of fear that others would recognize me as Jewish, but at age seven it was performed at a Jewish hospital in Rome. It hurt, but I was thrilled.”

A concentration camp barrack, Italy (Photo: shutterstock)

A concentration camp barrack, Italy (Photo: shutterstock)A Miracle With a Grenade

Soon after Israel’s establishment, the family immigrated. “We were taken from an immigrant camp near Hadera to Bat Yam in a truck. While my mother was looking at houses, I, a nine-year-old survivor with no idea what life was about, spotted what looked like a chocolate bar shaped like an etrog. It was hard on the outside, but I thought there must be sweet chocolate inside. A metal handle was attached, and I assumed pulling it would open the candy. Less than a second before I pulled it, an agency worker noticed me. He snatched it from my hands and threw it into a bunker. Seconds later, a grenade exploded with a deafening blast. That man saved my life.”

Mom Hilda Jacobi

Mom Hilda JacobiBuilding a Life in Israel

Nearly seventy years have passed since Ilan arrived in Israel. He became a teacher and later lectured in English and history at Tel Aviv University.

One highlight of his life was attending the ceremony where the nun who saved his family was honored as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem. “My whole family went to Rome for the ceremony. The next day, every newspaper in Rome covered our story. It moved me beyond words.”

Ilan with his descendants and grandchildren during the last Sukkot

Ilan with his descendants and grandchildren during the last SukkotIlan’s grandparents passed away in Israel, and he cared for his mother until her final days at age 87. Even when she suffered from Alzheimer’s, he arranged for constant care and stayed by her side.

Today, Ilan is a proud grandfather of 18. “I try to be the best grandpa I can. My children and grandchildren are all observant Jews. The joy I feel when my grandchildren run to me with a good grade, a lost tooth, or just a funny story, fills the void of a childhood I never had. For me, this is the ultimate victory. The Jewish people survived.”