"A Man Suddenly Appeared, Mumbling: 'Don't Board the Train, Those Who Board Won't Return,' and Disappeared"

The Holocaust survivor's harrowing journey through artistic expression

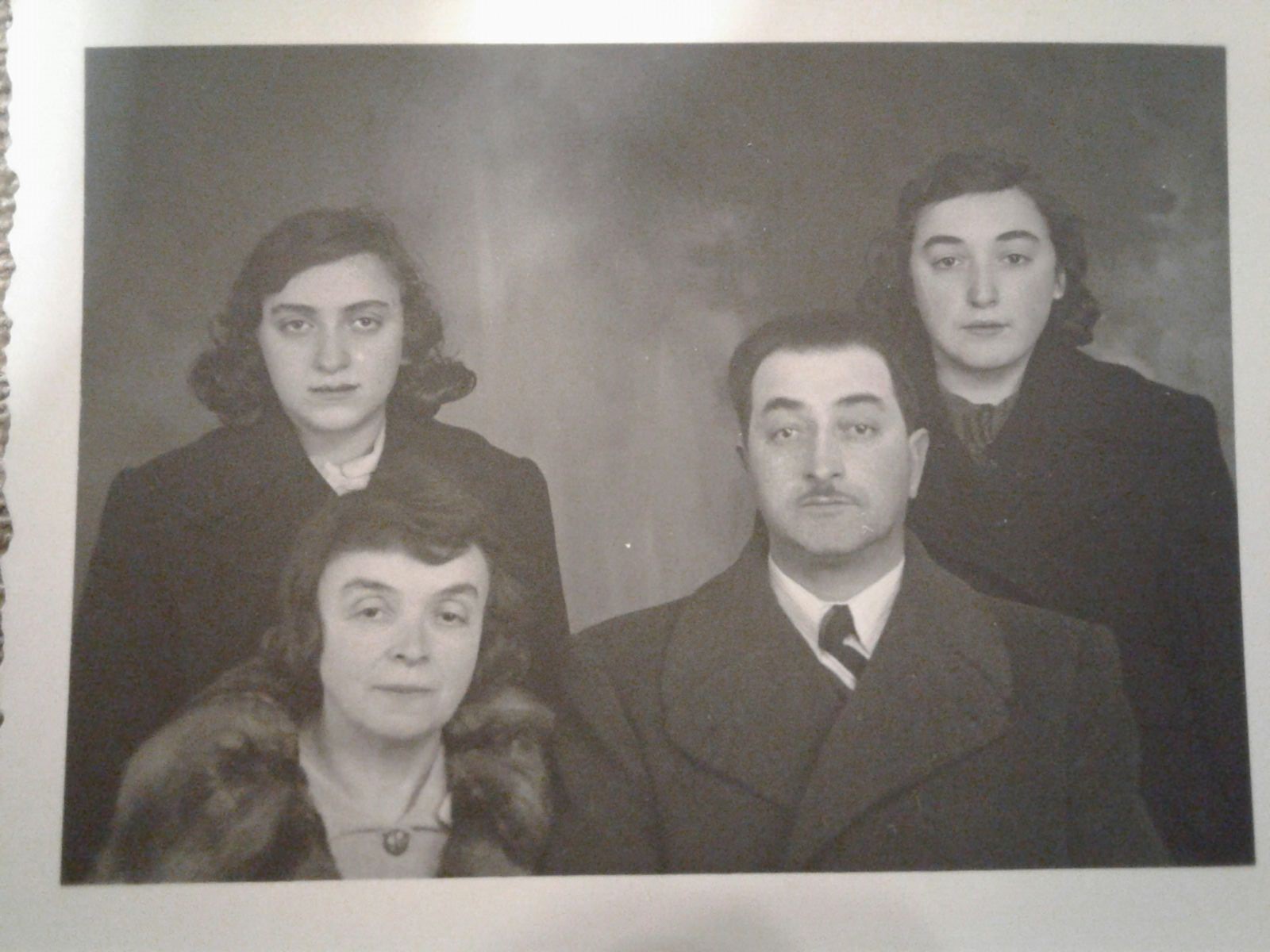

Deborah's grandmother and in the circle Deborah

Deborah's grandmother and in the circle DeborahHolocaust Remembrance Day is here. It is impossible to ponder it without recalling the chilling and harrowing stories of the tragedy experienced by our people. However, for artist Deborah Carl, a third-generation Holocaust descendant, these are memories that do not end with one day but accompany her throughout the year. This is because, as an artist, with a bachelor's degree in education for arts, and a teacher leading the art specialty in three different schools, she finds herself documenting the Holocaust in various ways.

"It's not that I officially decided I specifically want to document the Holocaust," she explains, "but engaging in the field of arts naturally leads me to vent what I'm going through. In recent months, I've been developing this area even further through the 'Art and Faith' initiative led by Attorney Omer Yankelevich".

As an example, she shares an experience she recently underwent: "Three months ago, I gave birth to a sweet daughter, but for half of the pregnancy, I was hospitalized under challenging conditions, with uncertainty if I would complete the pregnancy safely. These were life-and-death fears, and the only thing that gave me strength was painting. I sat and painted, pouring out everything in my heart, and truly, art is the greatest and most precious gift I have".

Deborah's grandmother and her family

Deborah's grandmother and her familyLight in Times of Darkness

Deborah came to paint the Holocaust because of her grandmother's stories – Gerda Lixenberg (née Zwiek), who survived the dreadful war. "Grandma passed away when I was about seven. I remember her as very ill, and I did not really have a chance to experience her or her story. But she had a diary she wrote in English immediately after the war, and I did read it over and over. What's so special about this diary is that it's full of emotion. Grandma constantly points out the optimistic and strong side; she places great emphasis on the moments of light during the Holocaust, although it’s clear between the words that she went through crazy and terrible things there, but she keeps mentioning the great and amazing miracles".

Deborah's grandmother

Deborah's grandmotherIn one of the instances described in the diary, Deborah's grandmother describes a day when she, her mother, and her twin sister were starving beyond description: "One day," she writes, we had no money at all and all three of us were very hungry. Mother suggested we go out for a walk which might distract us from the hunger and pains. It was early evening, the darkness started descending, and we were walking dejectedly on the street. Suddenly mother voiced a wish that crossed her mind: 'If only money would rain down on us from the sky just enough for a piece of bread to help us through this night.' Mother smiled dreamily, and suddenly a gust of wind brought bills falling from nowhere. They fluttered and landed near us. We were very surprised, turned around, and saw no one. The street was deserted. We tried to find the source, but all the tall buildings were dark and empty. Then the wind stopped, and we bent down and picked up the bills, all in very small denominations. After some thought, mother said: 'If only I had prayed for a little more...' And we then ran towards the market that was just about to close, and we had enough money that night not only to buy bread but even butter and some spreads." And Gerda concludes the story: "We could never explain this event. It was simply a miracle".

Deborah's grandmother and her family

Deborah's grandmother and her familyLike Sheep to the Slaughter

"Since I started engaging in art, as a high school senior, I was deeply connected to the Holocaust," Deborah shares about herself. "In those days, I was required to submit a final project and created an installation (a kind of sculpture) measuring two meters by two meters. It was a porcelain plate with a fetus placed on it, a fork stabbed in its throat, and a knife placed beside the plate, as if someone is trying to eat the fetus. I called the piece 'Autumn Nazism'. Through it, I tried to convey the sadism of the German nation, who seemingly eat with silverware on a plate and try to keep themselves clean, while the helpless Jews are like the defenseless fetus, led like sheep to the slaughter, with the face of a martyr. The fork and knife express the tools used by the Nazis may their name be erased – with the fork they practically murdered the Jews and annihilated them, while the knife is only threatening from the side, not touching, but present. It expresses the humiliations and psychological oppression the Jews experienced".

The reaction of the school to the installation was, according to Deborah, shocked. "The staff was so horrified by what I had prepared that they decided to set up the project in a side room, and at the entrance, there was a sign indicating what was about to be displayed, so every student could choose whether to enter the room or not. The truth is that I understood it was something jolting, but that was exactly my goal. As a third-generation Holocaust descendant, I felt compelled to express the difficult emotions that accompany me. I grew up with these stories, and they were what accompanied me".

In the midst of this, Deborah recalls another story her grandmother documented in her diary: "Grandma recounts that during one of the upheavals, she, her mother, and sister reached a city in Italy and were seeking a place to hide. They entered a parking area and thought they wouldn't be found there, but one night they discovered a notice waiting for them, stating they had to report to the municipal building the next day. It was clear to them someone had probably informed the authorities about them, but they had no choice. So, the next morning, fearful and trembling, they appeared at the municipality. My grandmother was the one who went in and spoke to the officer because she spoke better Italian than anyone else, and the officer immediately concluded: 'You're Jewish.' Then his partner entered the room and announced that if they were Jews, they must call the Gestapo. The first official dealing with them seemed gentle, and he turned to his friend and said: 'Listen, it’s not a good idea to call the Gestapo now, because by the time they come and register the details it will be six in the evening, and we'll be stuck here. Let's agree with the girls that they will report back to us tomorrow, they won't be able to get far anyway, and tomorrow we’ll call the Gestapo.' And Grandma writes in her diary:'We promised him we would return the next morning at eight and indeed were released. That very day, we fled relentlessly and were saved. It is clear to me that this official at the municipality knew that this is what we would do, he simply helped us escape, he saved our lives'".

On the Train Tracks

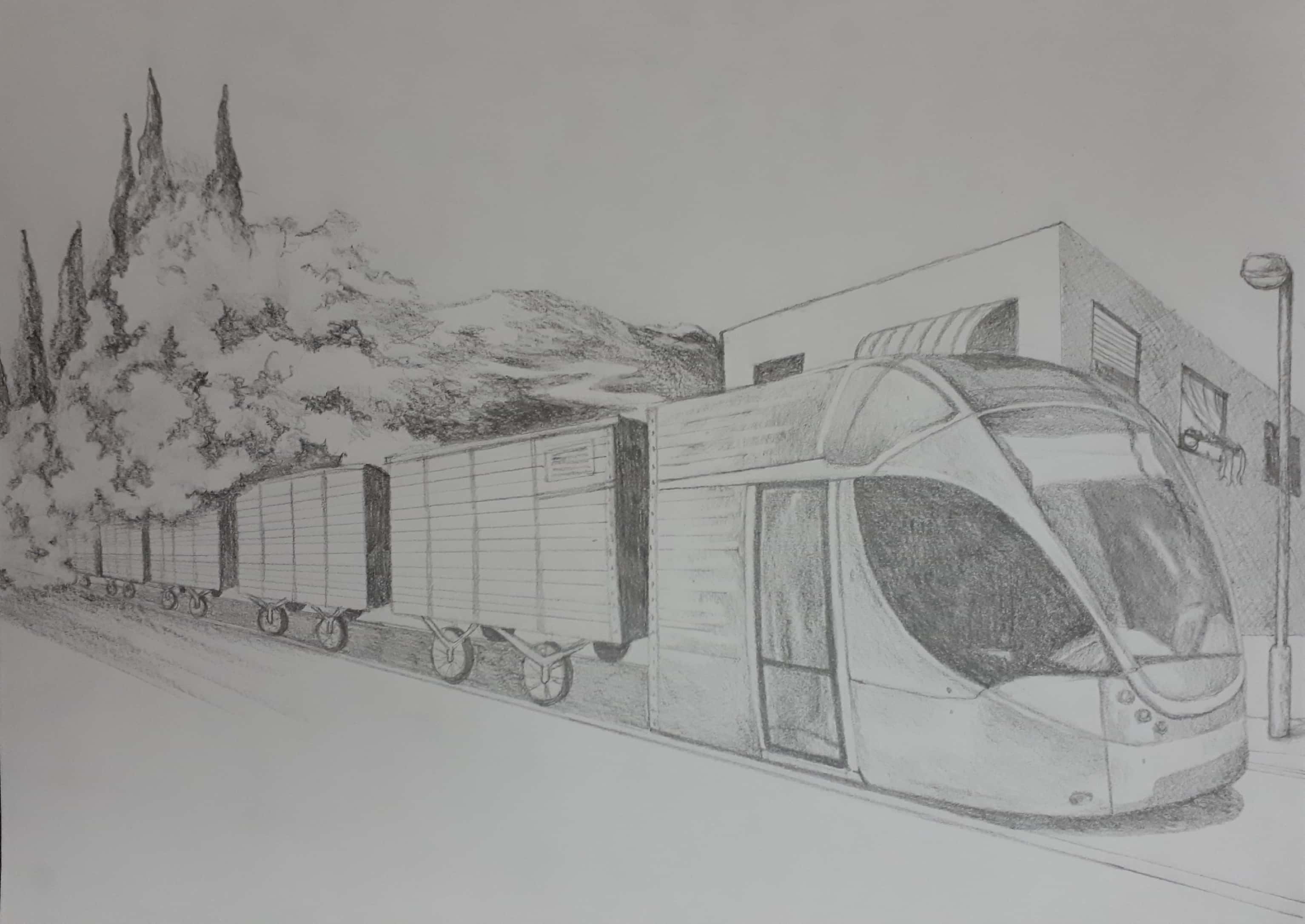

But one of the greatest miracles Gerda experienced occurred after her father was sent to a labor camp. "My grandmother remained with her mother and twin sister," Deborah shares, "they didn't know where her father was, and the three of them were desperately trying to escape Italy. They were running towards the train station, and as they arrived, they saw a train ready to depart, all the carriages were full, only the door of one car was slightly ajar. They attempted to squeeze through, and then, Grandma describes, one of the workers approached them. He walked slowly with a lantern in his hand, swayed it and mumbled towards them in a low tone: ‘Those who board here do not get off, this train leads directly to the extermination camp.’ And Grandma adds: 'Thus he walked and disappeared into the darkness. We saw him just like an angel who came to save us.'"

Unable to contain herself, Deborah chose to express the train story in a special drawing showing the train to the extermination camps, in its final carriages becoming the light rail traveling through Jerusalem, the holy city. "This is how I expressed what happened to us, how despite the harsh history and the abuse of our people, as a descendent of the Holocaust generation, I can freely ride the light rail in Jerusalem. This is our greatest victory."

In conclusion, she signs off: "My dear grandmother survived the Holocaust with her mother and sister. They immigrated together to Israel and later reunited with their father, reuniting and establishing generations that prove the Jewish people will never be obliterated."