Eliran Aaronoff: "Grandpa's Wine Saved Our Lives"

Over 150 years ago, the Haimov family began producing wine in Bukhara. They could not have foreseen that this wine would be the key to their survival during World War II and their immigration to Israel. Eliran Aaronoff, a fifth-generation winemaker, shares their remarkable story.

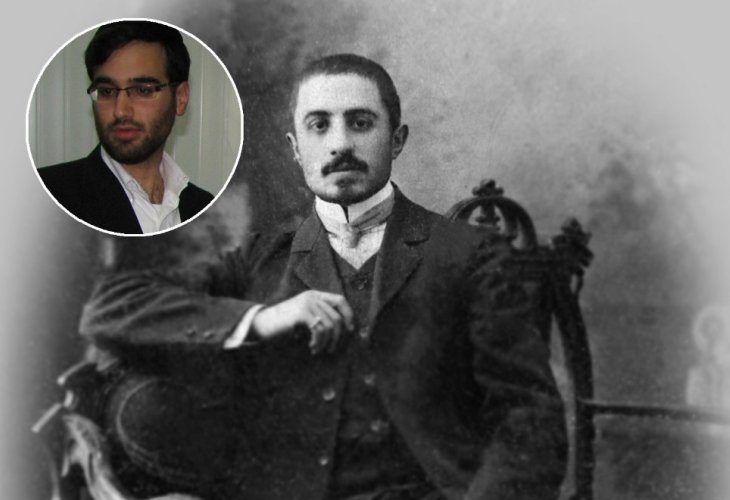

Photo of Rabbi Haimov (may his memory be blessed) and in the circle Eliran Aaronoff

Photo of Rabbi Haimov (may his memory be blessed) and in the circle Eliran AaronoffWhat does the word 'wine' mean to you? For most of us, wine is a drink associated primarily with Purim and Passover and is used for Kiddush on Shabbat. However, for Eliran Aaronoff, the founder of the Aaronoff Winery in the Judean Hills, it's a life's work.

"I was born in a wine household," says Eliran. "My entire family makes wine—my parents, uncles, everyone. As a child, that's what I saw; even at my grandparents' house, they always made wine, and I was very connected to it. Over the years, I developed a personal touch for wine and fostered a keen interest in its production."

Eliran, as an Orthodox Jew who studied only in religious institutions, gained his expansive knowledge through experience and by learning his family's incredible story along the way. "This is a story of Jewish heroism," he says with emotion, "because our winery wouldn't exist if my family hadn't survived through very difficult times in history."

The Iranian Citizenship That Saved Us

The story begins in Bukhara over 150 years ago. "My great-great-grandfather, R' Yona Haimov, lived there in Uzbekistan," explains Eliran. "Bukhara was a completely Muslim city, and since Muslims prohibit wine, Jews were banned from selling it. Each family made their own for Kiddush and celebrations, including my great-great-grandfather."

Where did he get grapes?

"That's not a problem. Uzbekistan is a fertile agricultural area, and grapes were always available there," clarifies Eliran. "But unlike other Jews who made wine solely for personal use, my grandfather's name spread far, and many wanted to buy his wine. So he produced and sold only to Jews. He was an expert in producing various types of alcohol with unique production methods."

But winning income was not the only gain; wine also provided their safety. "During the Russian Tsar's rule, Jews were forbidden to engage in free trade. R' Yona, wanting to remain in wine production, met with the Iranian ambassador in Russia and unbelievably obtained Iranian citizenship for the whole family for 300 gold coins."

"This was a remarkably unusual move back then," he emphasizes, "and no one understood why R' Yona insisted on paying such a hefty sum for a business that might not succeed. Only years later did it become clear that the Iranian citizenship obtained for the family saved his descendants' lives."

Manual harvest in the winery's vineyards

Manual harvest in the winery's vineyardsMeanwhile, R' Yona continued wine production, and thanks to foreign citizenship, he expanded the business. Eventually, Eliran notes, he passed away, but his children maintained the winery, especially his son known as 'Rabbi'. Shortly thereafter, R' Yona's children and wife decided to immigrate to Israel. Although security in Bukhara was calm at the time, Iranian citizenship expedited the process. Thus, they left Bukhara, transiting through Iran before reaching Israel.

"But my great-grandfather, 'Rabbi', did not immigrate," Eliran stresses. "He had young children at home, and he and his wife decided it was better to stay in Bukhara and continue the wine business, planning to immigrate later, remaining in Bukhara."

However, their plans were interrupted within a few years. The Bolsheviks came to power, trade was banned, and anyone wanting to work had to go through the government. "Grandpa Rabbi realized he had no future in Bukhara," says Eliran. "He wanted to leave everything and move with his children to Israel, but a rigid regime started. In 1938, hundreds of thousands, including Jews, were arrested. Grandpa Rabbi was taken to a concentration camp in Tashkent, Uzbekistan's capital, and never returned. We still don't know his burial site."

The appearance of grape pomace after traditional pressing

The appearance of grape pomace after traditional pressingWhat about his wife and children?

"Mazel, Rabbi's wife, was widowed but continued to engage in wine-making and managed the family business by herself. She produced wine nonstop and taught her children the secrets of wine-making," Eliran explains. "Yosef, Mazel's son and my grandfather—my mother's father—also continued in enology but realized there's no future in Bukhara and decided to escape."

Here, Eliran highlights that the decision of R' Yona to purchase Iranian citizenship proved advantageous again. "It was during the challenging times of World War II," he recounts, "there was no transportation, no escape routes; all borders were closed. But Yosef remembered his Iranian citizenship. It was truly a miracle. He fled to Iran with his sisters, bribing countless people along the way, and eventually reached their family in Iran. They arrived with nothing, only pictures, and, of course, wine-production secrets."

Barrel room

Barrel roomWine with an Israeli Flavor

Eventually, the entire Haimov family moved from Iran to Israel and continued private wine production. Eliran was the first to leverage this heritage, establishing a winery in the Judean Hills with special varieties named after his ancestors, whom he feels owe his life and family's existence.

Do you use the same wine-making secrets they used in Bukhara?

"I create the same style of wine, but I can't use the exact methods since we don't have the same grape varieties in Israel that my family had in Bukhara. But having lived these experiences and seen the lifestyle, I've adapted those directions to better suit the Israeli wine industry."

And what's it like being an Orthodox winemaker?

"Honestly, I feel it's nothing less than a mission. I frequently experience the concept of 'Great is the sip that brings people closer,' because people from all sectors visit my winery and each finds something they enjoy."

"Recently," he remembers, "buyers from China visited. They knew nothing about the Jewish people or Israel. When I handed one of them a wine bottle, he turned it and asked: 'What is this signature?' pointing at the kosher seal. There was a translator there, so I asked him to convey my words exactly. I then began to explain about Israel and the Jewish people, about the Bible—the Book of Books. I mentioned, in a sort of gesture, that the Chinese are also referred to in the Bible and quoted the source. I explained that Israel is distinguished by seven species, including the vine that produces wine, and that's why wine made in Israel is superior, as a gift from the Creator. He stood with his mouth wide open; I felt privileged to make a significant Kiddush for Hashem."

By the way, Eliran notes that non-Jewish tourists often visit the winery. "They are all very surprised that we adhere to special mitzvot like Shmita, tithes, orlah, and more. For us, it's natural, but they are stunned. They think we incur huge losses because of it and can't understand how we can keep these commandments."

Just before Purim – can you give us a tip for proper drinking?

"Generally, for those unaccustomed to drinking wine, which I think is most people, any wine will make you feel weak, regardless of the specific variety. However, since there's a mitzvah to drink wine during Purim, it's best to consume primarily dry wine. Still, the most important advice is to drink wine with food and not on an empty stomach. That way, you can be joyful without reaching states of vomiting, weakness, or discomfort."