For the Woman

From Plastic Bags to Spiritual Art: The Inspiring Story of Sigal Maor’s Eco-Creative Journey

How a religious-returning artist transforms discarded materials into meaningful Jewish art — blending sustainability, emotion, and faith in every piece

Sigal Maor

Sigal MaorPlastic bags, old newspapers, colorful tea wrappers, bottles, boxes, milk cartons — these are just some of the raw materials used by Sigal Maor, an artist with a uniquely creative touch who has spent decades creating primarily from discarded materials.

“Love for art and creativity began in childhood,” Sigal tells us. “I was always drawn to crafts of all kinds, to the projects we did in school. After the army, I studied at the University of Haifa for a bachelor’s degree in creative arts and philosophy. My dream was to advance and develop professionally as an artist, but the plans changed a bit.”

They changed because, during two years of living in the United States, Sigal and her husband began their journey toward religious observance. “There, in the Diaspora, our hearts opened,” she says. “Immediately after returning to Israel, we participated in a seminar that led us to begin keeping Shabbat and strengthening religiously. At the time, we were living near Haifa and connected to the community in Rechasim.”

“The process of coming closer to Hashem, to Torah study and mitzvot, filled me up and initially took over my entire world,” Sigal explains. “But as an artist with a creative soul — someone for whom art was always central, I immediately faced questions: How should I relate to the world of art? What place does art now hold in my life? Can it merge with a life of faith and Torah? I continued creating, but on a small flame. I felt I needed time to understand the place of art in my new world.”

Meanwhile, she worked as a kitchen designer. “It’s not exactly art, but it still involves creativity and aesthetics, and at that time financial considerations were decisive. Deep down, I felt a sense of loss — a longing for true artistic creation.”

A Return to Art

The Maor family moved to Ashdod. “My husband was serving in the Navy base there, so we moved with our two children. I would occasionally pass by the Ashdod Art Museum and feel it calling to me. I wondered — should I go in and submit my resume? I had such a strong desire to return to the world of artists and creators. By then we were already ten years into religious observance — my heart was calmer, yet still yearning.”

At that stage, she already understood that “Hashem does not give a person talents and gifts for nothing; the goal is to use them, not ignore them. The question was how to use them, and to what degree.”

“I knew the art world well,” she explains. “I knew that good art comes from a place of totality — absolute emotional and mental devotion, sometimes to an extreme. On one hand, I understood it; on the other, I recoiled. I deeply felt that a person should be totally devoted only to the Creator. I didn’t want the passion for art to take over or control me. It felt almost like a form of idol-worship. I wanted to create from a place rooted in Jewish, faith-based consciousness.”

“One quote that pushed me back to creating was something I read from Rabbi Kook: ‘As long as even one sketch hidden in the depth of the soul has not been brought to fruition, the work of art remains incomplete.’ I understood that the need to create is a gift I was given — not something to suppress, but something to channel properly. I pray that Hashem helps all of us use our gifts to sanctify His name, not for personal honor.”

Art Filled With Emotion

Sigal eventually submitted her resume to the museum and was hired. “At first, I worked as a tour guide for the exhibitions — guiding is a form of interpretation that enriches the way visitors experience the artwork. I was so happy to return to the creative world. Alongside guiding, I began participating in various creative projects and teaching workshops for children and adults. The focus was creation from discarded materials, often household items with tremendous added value. It develops creative thinking, saves material costs, and fosters environmental awareness. Any material can become the basis for meaningful, challenging creation.”

One of her most powerful works was created during Operation Protective Edge. “Just as the operation began, my eldest daughter got engaged,” she shares. “I remember those days as deeply confusing. On one hand, joy! My daughter was becoming engaged to a Torah scholar. But on the other hand — how could I rejoice when soldiers were falling in battle and mothers across the country were crying? I felt I needed to express these emotions and somehow connect to those families.”

“One day, I asked my husband who was serving in reserves at the time, to bring me a military shirt. On it, I embroidered portraits of fallen soldiers, and between the faces I stitched my thoughts — a stream of consciousness, almost a conversation with God. It was a kind of ‘hitbodedut-therapy’ on fabric. I felt weak in my faith and emotionally overwhelmed, and the embroidery soothed and strengthened me.”

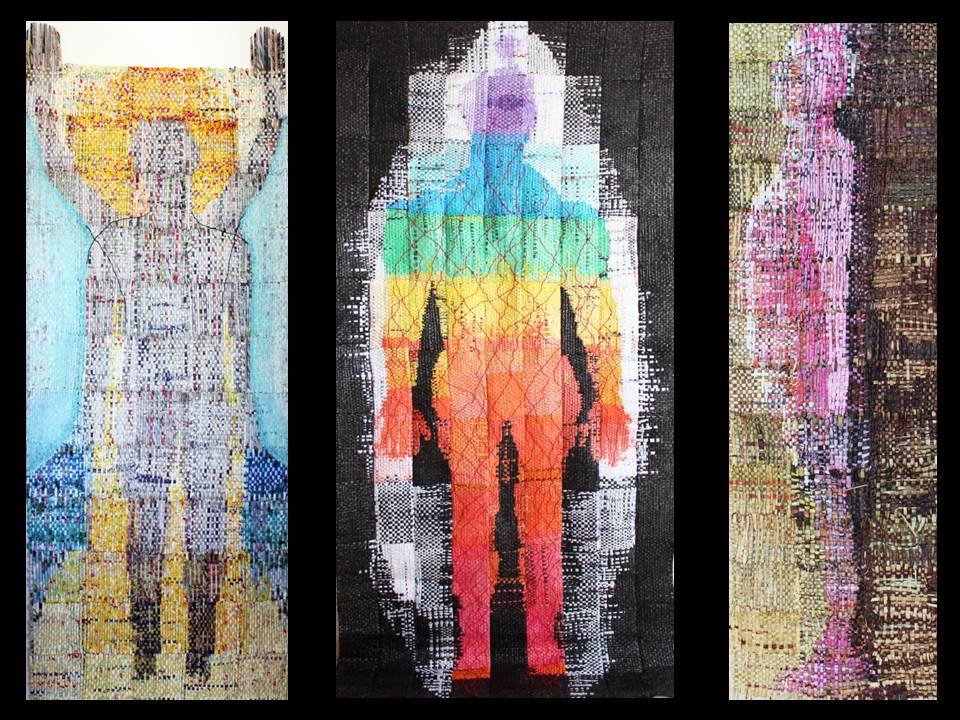

Creation Adam-Adamah

Creation Adam-AdamahA Whole World Made of Plastic Bags

Interestingly, one of Sigal’s favorite materials is plastic bags. For Sigal, they always had value. She uses them in knitting, weaving, braiding, and embroidery.

One of her most striking works is titled “Adam–Adamah”, inspired by the Hebrew connection between “man” and “earth,” symbolizing the physical body that returns to the soil and the eternal soul striving to resemble its Creator. The piece is crafted in three woven layers: plastic bag strips as warp threads, and rolled newspaper or palm fronds as weft threads. The symbolism is expressed both in the imagery and in the mix of organic, biodegradable materials with long-lasting plastic.

Sigal also cites a passage from the Talmud (Bava Kama 50b) about a man removing stones from his property onto public space, only to later stumble over those same stones when the property was no longer his — an early message of environmental responsibility. She created a four-part piece (27 cm each), woven from bags and newspapers, with the story embroidered onto it.

And when Sigal searched for hints about plastic bags in Jewish sources, she discovered a verse in Psalms that includes the word “sakit”: “You loosened my sackcloth and girded me with joy.”

“It felt like divine providence,” she laughs. “I had been working with bags so much — then one day at shul I opened Tehillim and my eyes lit up…”

“In general,” she adds, “I think the plastic bag is a metaphor for life. It’s considered the lowest, most disposable thing. But sometimes, it’s precisely the lowliest materials that can be brought to the highest places.”