From Zionism to Faith: Rabbi Yigal Miller's Journey

Rabbi Yigal Miller, once the epitome of Israeli education and patriotism, organized Independence Day ceremonies at his school and was chosen by the government to teach Zionism to youth. However, everything changed when he realized the truth about the land's foundation.

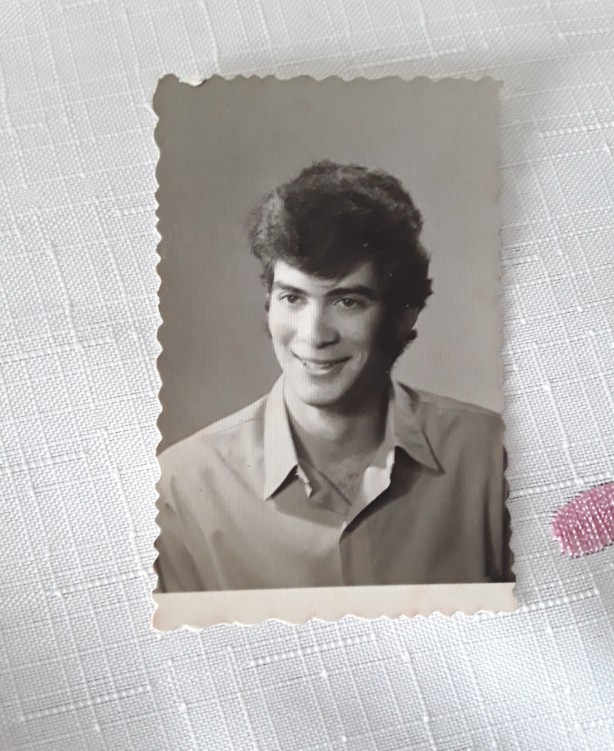

Rabbi Yigal Miller

Rabbi Yigal MillerEvery year, when the 5th of Iyar arrives and Israel celebrates its existence, Rabbi Yigal Miller is instantly swept back to his childhood in the Carmel neighborhood of Haifa.

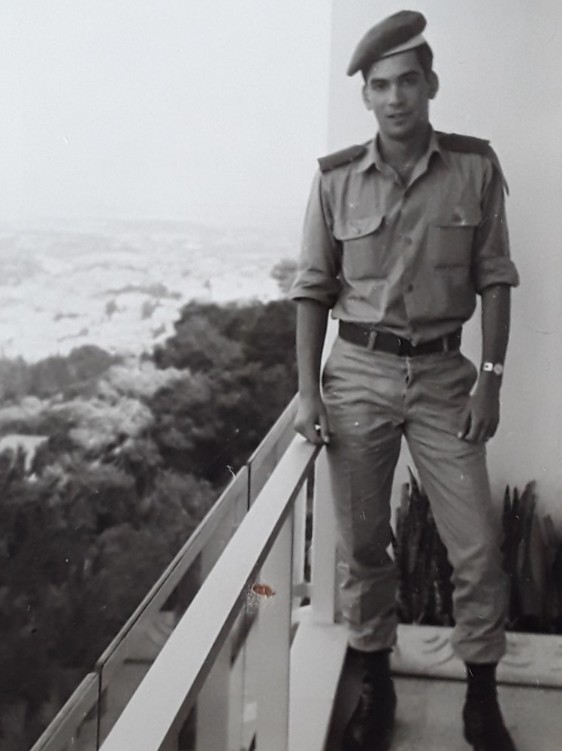

"I was born in the land," he begins his story, "and I was the pride of Israeli education—through preschool, primary school, then high school, military service, and even university. I followed the expected path. I joined the flight course and served 17 years in the Air Force reserves, participating in wars and operations like the Yom Kippur War, Operation Litani, and more.

"I was a person driven by values and Zionism," he adds, "and came from a well-to-do family. My friends were stylists and my father was a renowned landscape architect nationally and internationally. He designed the Safari in Ramat Gan and the Biblical Zoo in Jerusalem. I was proud of him.

Rabbi Yigal Miller in his youth

Rabbi Yigal Miller in his youth"When I was 14, the Six-Day War broke out and the country was in turmoil. We witnessed miracles as the IDF conquered much of the Middle East. Some lands we kept, and some we left. They called them 'liberated territories' and 'occupied territories'. There were massive debates about who the land belonged to and why we were fighting...

"I remember during the war, my leftist teacher divided the class into two. She told half, 'You are Israelis', and the other half, 'You're supposedly Arabs', and then held a class hour asking each group to justify why the land belonged to them.

"That class hour was unforgettable. It was intense and dramatic. Quickly, I was surprised to find that for every argument the Israelis made, the Arabs made a matching one. They said, 'Our ancestors fought for this land', and the Arabs claimed the same. The Israelis said, 'Our ancestors are buried here', and the Arabs echoed them. Finally, the teacher concluded with the decisive statement: 'The land belongs to us – the Israelis, because it was promised to Abraham our Patriarch.' As a young teenager, I was shocked. I went home disturbed for weeks. Is this what our leftist teacher was selling us? What connection does she have with religious reasoning?

"Later," Rabbi Yigal says, "I understood that the teacher simply lied. Even saying half-truths is a lie. Indeed, the land was promised to us since the days of Abraham and later Isaac and Jacob, but it wasn't just given as a gift. It was conditional upon 'If you walk in My statutes and keep My commandments,' only then—'I will grant peace in the land and you shall dwell safely under your own vine and fig tree.'

"There were other instances in my childhood when I heard half-truths, causing me much agitation. This happened during the global 'Let My People Go' campaign for the release of Russian Jews before the Iron Curtain fell. Even then, as a young boy, I noticed something missing—what is 'Let My People Go'? Why should the Jewish people come to this land? Later, as I learned more, I realized even this was half a truth. The objective wasn't just to come to the land, but to 'Let My people go so they may serve Me.'

Another thing that disturbed the young Rabbi Yigal was the emblem of the nearby Reali School in Haifa, which bore the inscription 'Walk humbly'. I remember looking at the students who walked around improperly dressed and asking myself: 'Is this humility?' Only later did I learn the continuation of the verse—'with Hashem your God'.

Not by Might nor by Power

Here, Rabbi Yigal pauses to note that every soul comes into the world with unique traits—one is a painter, another a musician, a third an artist, and a fourth a poet. Hashem gave each soul its traits. "To my wife and me, He gave the trait of truth," he says. "Neither of us can stand falsehood, and I believe that's what led us to seek the truth.

"We knew each other since high school because we studied in the same place, but on Shabbat nights, when our friends went to clubs and entertainment, we stayed home, preferring the quiet. At first, it wasn't about following halacha, but simply a lack of interest.

"In twelfth grade, a shocking event occurred when some kids broke into the history teacher’s house and stole the matriculation exams. It felt like a slap. I was very shaken, and so was my wife, who studied two grades below me. It made us think about values. The more we thought, the more we realized all the values we were raised with were unstable and subject to change. For example, it was once illegal for an Israeli citizen to hold dollars. Yet one day, dollars were found at a famous political figure's home, and suddenly by morning, the law changed, and holding dollars became permissible. I already understood that to educate truthfully, there must be stabile, strong values. I looked around and found none.

Rabbi Yigal Miller today

Rabbi Yigal Miller today"My wife and I," Rabbi Yigal continues, "grew up in very Zionist families that revered Israel with all their soul. I can't describe the number of photo albums in our parents’ home after the Six-Day War. I even remember the names on the albums: 'Six Days in June – IDF in its Glory' and another album: 'All the Honor to the IDF', with photos of bombings of Egyptian airfields. The documentation was authentic, nothing falsified, but even then, I was troubled by the 'My strength and the might of my hand' mentality. How could we boast about the IDF’s power when miraculous events helped us? I remember Tel Aviv and other cities prepared stadiums and national parks to serve as mass graves if needed. People expected the worst. So why not acknowledge the miracle?

"Years passed, and I served in the army myself. I joined the Air Force, and during the Yom Kippur War, I saw firsthand the Air Force's collapse. Defense Minister Moshe Dayan called it the third destruction. I saw aircraft run out of fuel and drop like flies. I served at a base and saw planes return burnt and damaged. Pilots were captured by the enemy, and our base was bombed. Morale plummeted. There was total collapse. To boost the pilots’ morale, the base commander flew, but during one of the bombings he was hit, and as far as I know, his body hasn't been found to this day. This mindset of 'My strength and the might of my hand' shattered before my eyes. The general atmosphere where I served was completely mixed; they didn’t adhere to basic things, and I constantly wondered what kind of army this was. Could we really win wars this way?

"After finishing military service, I went to university. Meanwhile, there was a big upheaval in the country with the publication of 'The Letter of the 12th Graders to Golda'. The letter was sent by 58 high school students mainly from Jerusalem, Rishon Lezion, to Tel Aviv. They wrote that they weren’t sure they could fulfill their duties in the army because they didn’t feel connected to the state and might find it hard to enlist. That letter shook the country, and as a result, it was decided to enlist students trained in the social sciences and humanities at leading universities into a fast-track Zionist course and employ them as paid lecturers to instill Zionism in pre-draft youth. I was one of those students.

"I became a paid Zionism lecturer. I spoke at schools and high schools, but during my lectures, I noticed I couldn’t even convince myself. I clearly saw that Zionism's essence since its inception was to create an alternative to the Torah, producing a new kind of Jew. Like caffeine-free coffee, their aim was to make Torah-free Jews. So new values were introduced, like developing wastelands, draining swamps, and Hebrew labor. They turned work, seen in the Torah as a curse 'By the sweat of your brow you shall eat bread', into an ideal. Shabbat was secularized with the slogan: 'Treat your Shabbat as a weekday'. The idea was—need rest? Do it on Tuesday or Wednesday, but not on Shabbat. Even Eastern Jews who came to the land observant and Shabbat-keeping were secularized systematically. I discovered all these things in the Zionism course. But the hammer blow was the book 'Perfidy'—a secular book describing the Kastner trial, but it truly opened up the misdeeds of the state's founders and leaders. For me, it sparked a dramatic transformation.

Avoid Uncontrolled Leaps

The journey towards returning to the faith, Rabbi Miller says, was gradual. "My parents came from religious homes and over the years stopped keeping mitzvot, but my grandparents came to the land before the Holocaust and were very religious. As a child, I heard the Grace After Meals at their home, also attending Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah services with my grandfather, and evidently, something from my childhood memories clung to me and influenced me.

"Today, it's common for people to make rapid returns to faith, sometimes within days. But for my wife and me, it was entirely different. We undertook very deep work and returned to faith slowly, step by step. It took time before we felt capable of independent thinking and analysis, not fearing to draw conclusions. Even when it meant leaving societal comforts, enduring family difficulties, and ultimately accepting the commandments totally and choosing a Charedi lifestyle."

The process wasn’t easy, "but we weren’t afraid," he emphasizes, "We both felt we discovered something true, leading us to the right place. After marriage, we lived in Haifa but later moved to Jerusalem, leaving our past behind."

Today Rabbi Miller is a scholar. "We were blessed with 10 children and many grandchildren," he shares happily, "In the mornings, I study in a kollel, and in the afternoons, for 14 years, I've been teaching at the Ashrei HaIsh yeshiva of Rabbi Ben Porat. We strive to build the young men's character educationally and purposefully, drawing from my life experiences and my profession as a social worker. I often speak with the boys and see myself in them. I continually warn them against uncontrolled and unsupervised leaps. Many who return to faith fall when they try to speed through the process too quickly. Sometimes they feel, 'We lost so many years, let’s make up everything at once', but without proper guidance, they may fall into deep despair, starvation, self-denial, fasting, penance, and eventually, dysfunctional family life. That's why I see immense importance in standing at the crossroads where I find myself."

His greatest satisfaction, he says, comes when he sees young men who have undergone the process, then advance to the country’s premier yeshivot, marry, and build proper homes in Israel. "These are my most joyous moments," he testifies.

To contact Rabbi Yigal Miller: veredbelts@gmail.com