When Art, Arks, and the Second Generation of Returnees to Judaism Meet

Rabbi Avraham Abargel has built over 100 arks in his lifetime, but his greatest satisfaction came six years ago when he founded the 'Derech Emunah' yeshiva for the second generation of those returning to Judaism.

You could call him an artist, a yeshiva head, or even a kollel student, but when speaking with Rabbi Avraham Abargel, he prefers to be called by his favorite title—the 'Ba'al Teshuva,' as 34 years ago, he discovered his connection to Hashem. "I was born into a non-religious family, and since I can remember, I was an artist, heavily involved in sculpture and painting," he recounts. "At the age of 22, I was exposed to the teachings of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, which led me to search for the truth. Gradually, I came closer to Judaism."

Early in his journey, right after his marriage, Rabbi Abargel knew he wanted to be a kollel student. "I studied as a kollel student for several years, completely abandoning my art hobby. But at some point, I felt the need to create, and as our children were born, I needed to make a living. So I began working with Judaica, paintings, and marriage contracts. Because I wanted something Torah-oriented, I also became a scribe. Yet, for most of the day, I continued my studies as a kollel student."

Rabbi Abargel notes that at one point he began to feel some difficulty with the scribe work. "My hands were aching, and creating required a great deal of effort. I consulted a doctor who advised me to strengthen my hand muscles, leading me back to sculpture and art. It was amazing—after 12 years without engaging in those fields, I returned and felt as if I was coming back to life. My dream was to create art in a synagogue, combining my faith and art."

A Dream That Became Reality

Rabbi Abargel's dream quickly became a reality through divine assistance. "At that time, I lived in Bat Ayin, and they asked me to create a memorial plaque for a donor who contributed to the local synagogue. I created the plaque, and the donor was so impressed that he ordered additional artistic signs for other synagogues he contributed to. Later, he asked if I could build an ark for a synagogue established in the settlement Carmey Tzur, and I jumped at the opportunity since, as I mentioned, it was my dream."

However, at that time, Rabbi Abargel had no idea where things would lead. "I worked for a while with that donor, and together we built arks for twenty synagogues. Over time, more and more inquiries came in, and I gradually became proficient in architectural design. This led me into the niche of overall synagogue design. Today, I not only build arks but also design synagogues as a whole, having completed projects for over a hundred synagogues."

What makes your creations so special? Why do people specifically reach out to you?

"I'll explain—usually, when people approach such work of designing a synagogue, they contact companies that specialize in it. These companies duplicate a model of a carved ark executed with their workers, who sometimes aren't even Jewish. The result is an ark resembling a beautiful wardrobe, but it's not art. Anyone genuinely wanting an artistic ark must find someone who lives and breathes it, who can match the ark to the congregation's character and the synagogue's general style. I live among my people, and whenever I'm commissioned to create, I see it as a new challenge, selecting materials accordingly—stone, wood, or bronze, among others, trying to understand what the community will like and what fits them. I'm not trying to do what suits me but what's best for them."

Rabbi Abargel also adds, "Today lacks what once existed—true artists who see each synagogue as a whole unit. Nowadays, people hire a carpenter for the ark, a plasterer for the ceiling, and someone else to build the ark without connecting the elements in the space. I strive to do something more—to create a synagogue atmosphere with a connection between everything in the space. Of course, budget constraints always exist, but even with cuts, I try not to compromise."

The Ark That Found Its Purpose

Tell us about a special ark you built!

Rabbi Abargel doesn't need to think twice before recounting the following story: "Several years ago, I was asked to prepare a stone ark for the Cave of the Patriarchs. They requested a stable and massive ark to withstand heavy use. Indeed, I prepared the ark. After an extended preparation period, I arrived at the cave to assemble it—this was after governmental approvals and ministerial signatures, given the sensitive area. But once I started assembling, Arabs arrived and began protesting, claiming that Arabs visit the cave for prayer certain days of the year, and they wouldn't accept the ark there. The matter escalated up to Abu Mazen, and I immediately received an order from the Ministry of Defense to halt the work and later, to remove the ark's stones from the cave. As a substitute, I made a bronze ark, and I kept the original at my place..."

(Illustration photo: shutterstock)

(Illustration photo: shutterstock)Yet that's not the end of the story. "Some time later, I received an order for a stone ark from a synagogue in Kfar Saba, and they insisted on having a stone ark. I told them that I had a ready one, but when I arrived at the synagogue, I saw that the hall was very modern and prestigious, whereas the stone style of the ark from the Cave of the Patriarchs was ancient. It simply wasn't right for the venue, but for some reason, they insisted. While we were deliberating, a dear woman named Bat Sheva Weinberg, who essentially established that synagogue in memory of her two fallen sons, arrived. She asked me where the ark was from, and when I told her about the Cave of the Patriarchs, she turned pale. 'My son, Dror Weinberg, a battalion commander in Hebron, was murdered at the Cave of the Patriarchs,' she said. "From that moment, everything became clear, and there was no room to discuss changing the style," he recounts emotionally. "Suddenly, we all felt that the whole building had been constructed to house this ark."

You can find Rabbi Abargel's special arks in many well-known places, such as the men's section at the Western Wall, the tomb of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, and the President's Residence. He also frequently restores ancient arks in various locations across the country.

"But the most challenging order came to me from the USA," he recounts. "A wealthy benefactor who donates substantially to Torah institutions decided he wanted an Italian synagogue built in his home, just like from the museum. The work involved a building style practiced 500 years ago, and he insisted on something authentic. He asked if I could do it, and I replied 'yes,' as I never say no. However, the task proved more complex than imaginable. I worked on it for two full years, but the outcome was stunning—a massive and splendid ark made of wood and gold."

Derech Emunah Yeshiva

But Rabbi Abargel does not rest on his laurels. As he explained earlier—he sees himself primarily as a Ba'al Teshuva, and as part of this, he often worries about the future of the children of Ba'alei Teshuva, known as the second generation of returnees to Judaism.

"I clearly see the challenges of raising the second generation, and there are many difficulties. As my children grew, I understood how real this issue is, as there is no suitable solution for children in such situations. They don't want to end up in mediocre institutions, but on the other hand, they cannot get accepted into the top institutions. This leads to high dropout rates among the second generation of returnees." From this understanding, Rabbi Abargel notes that he decided to establish the 'Derech Emunah Yeshiva.'

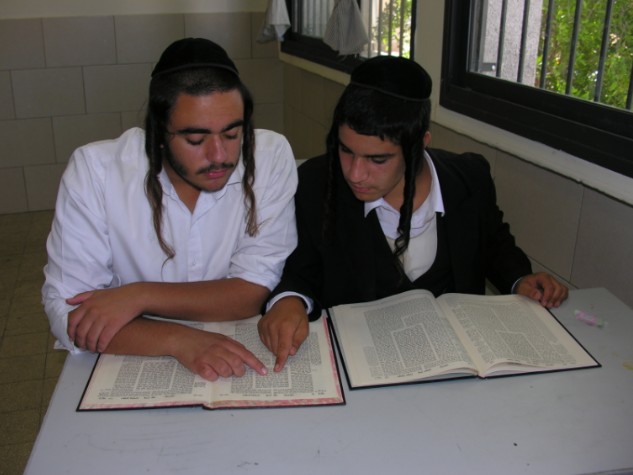

"I founded the yeshiva about six years ago, with the encouragement and blessing of Rabbi David Abuhatzeira," he explains. "I felt it was truly imperative, and thank Hashem, we currently have about 70 students studying with us, and many more want to join, but unfortunately, there's no space. The studies are at a very high level, the boys also take matriculation exams, and on the other hand, they strengthen greatly spiritually. It is a place with an amazing staff that invests heavily in the boys without judging them but knows to set boundaries when necessary." And the statistics speak for themselves, as Rabbi Abargel points out—dropout rates among yeshiva boys are virtually nonexistent.

But his major aspiration is to also connect the yeshiva students to the field of art. "I believe art can offer true therapy to the boys, allowing them to create and express themselves through creativity," he says passionately, "And that's truly my aspiration—to establish a department for architecture and art, enabling my students to engage in sacred art, as I'm fortunate to do."