Yehuda Greenwald, a Veteran Baal Teshuvah: "I Was Forced to Change My Perspective on the Teshuvah World"

Twenty years ago, he released a groundbreaking guidebook for Baalei Teshuvah, 'To Know the Land of Your Way,' encouraged and supported by Rabbi Shlomo Wolbe zt"l. Yet over the years, Yehuda Greenwald has noticed significant changes in the Israeli teshuvah world. What's the difference between the Baalei Teshuvah of the past and those of today, why are communities for Baalei Teshuvah desirable and recommended, and what role can Baalei Teshuvah fulfill if they remain in their previous environment?

Yehuda Greenwald has undergone several significant transitions in his life. Over thirty years ago, he embraced teshuvah and moved to an ultra-Orthodox neighborhood in Jerusalem, but this significant change was not the end. Seven years ago, Greenwald and his family left their established community and moved to Haifa to establish a Baalei Teshuvah community.

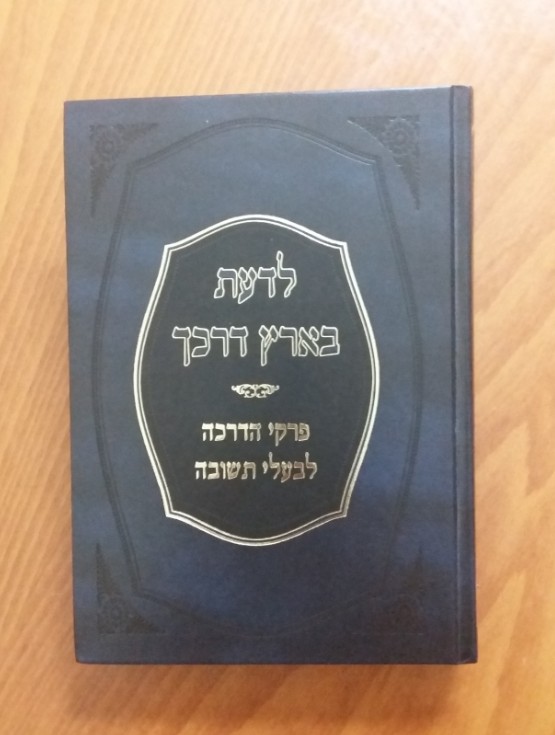

These personal changes aren't coincidental; they reflect thought processes he's been writing about for many years. "To Know the Land of Your Way," his book from 20 years ago, was groundbreaking in the guidebook genre for Baalei Teshuvah. Today, he's working on another guide, but in a different direction.

"I grew up in a National-Religious home, but after military service, I completely abandoned Judaism," Greenwald recounts. "Ten years later, I was a criminal lawyer working as a prosecutor in the police. During that time, I began to participate in group dynamics activities led by Danny Carmon. Danny was just beginning his path to teshuvah and started talking about it in our meetings."

Sparked by Carmon's interest, Greenwald attended an 'Arachim' seminar in Rechasim. This seminar was enough to convince him of the truth of the Torah. "For another three months, I continued working in the police and walking around without a kippah, but then I put on a kippah, resigned, and went to Jerusalem to study in a yeshiva."

After a year in yeshiva, Greenwald was introduced to one of the most significant figures in his life: Rabbi Shlomo Wolbe zt"l. "It started when the book 'Between Six Days and a Decade,' his discussions with kibbutzim and the army, came to my hands. I was astounded by what I read and thought I must meet the man. I started going to his teachings on Saturday nights at Yeshivas Kol Torah and later at Beit HaMussar. Over time, we developed a very close relationship, and I even studied with him one-on-one for two years. He was a great and open-minded man, with exceptional wisdom."

After three years of Torah learning in Baalei Teshuvah frameworks, Greenwald started combining studies at the "Mir" Yeshiva with working as a lawyer. In the meantime, he got married, had eight children, and seemed to be fully integrated into the ultra-Orthodox community in Jerusalem. "I never encountered issues of discrimination or acceptance into institutions. My connection with Rabbi Wolbe helped me, as did, conversely, my profession as a lawyer," he explains.

Despite personal success, Greenwald aspired to publish a guidebook for Baalei Teshuvah. "I felt there were pressing questions that Baalei Teshuvah face but do not dare to speak about deeply: issues of livelihood, their relationship with the ultra-Orthodox world, marital issues, Torah study, and more."

He worked on the book, "To Know the Land of Your Way," for nine years, supported by Rabbi Shlomo Wolbe. "I remember presenting a collection of questions to Rabbi Wolbe, saying that some I experienced personally and others were raised by friends, and these are questions that require answers. He read and told me: Indeed, a book needs to be written on this topic – and you should write it. We agreed that I would not publish the book without his review. We had discussions on the subjects, but he greatly valued the independence of students and allowed me to write without dictating. When I first showed him a chapter mostly quoting great Israeli figures, he said: 'It's all nice, but this is the part I loved,' pointing to a passage I wrote myself without quotes."

Upon completing the book and preparing it for publication, Greenwald began to have fears. "Rabbi Wolbe greatly encouraged me. At that time, my daughter was born, and we held a Kiddush at home alongside a small celebration for the book's release. He came especially and told me not to fear, and even added that within three months I would publish another edition and even open a kollel following the book. That's exactly what happened."

Over the years, however, Yehuda Greenwald's worldview underwent a change. "In retrospect, I understand that the book suited Baalei Teshuvah who integrated into the Lithuanian Ultra-Orthodox world. But the Teshuvah movement has taken a different direction since then." He points to the enormous numerical growth of those nearing Judaism in recent years – growth not necessarily reflected in a rush to ultra-Orthodox cities and yeshivot for Baalei Teshuvah.

Meeting the multitude of Baalei Teshuvah and religious returnees in our generation made Greenwald realize that what was – is no longer relevant. "The Baalei Teshuvah of the past were ready to leap into the fire. They entered a yeshiva or seminary, established a yeshiva home with the husband in a kollel, moved to live in an ultra-Orthodox city. Today it's different. I speak with people who have been 'in teshuvah' for five years, and in terms of mitzvah observance, they are where I was after three months. Yet, in some ways, they are sometimes more connected to Judaism than I was as a Baal Teshuvah with five years of experience."

'Connected' is the keyword here, he explains. Today's Baalei Teshuvah don't seek explanations for the truth of the Torah and proofs of creation. They want to feel connected to Judaism, to feel a deep emotional bond with the religious lifestyle. "I heard from Rabbi Uri Zohar that a contemporary Baal Teshuvah told him it's hard for him with the concept of cutting toilet paper before Shabbat. And when Rabbi Zohar asked what the big issue is, he simply said: 'I don't know, I just don't connect to it.' This is a typical statement of this generation."

The need to connect and remain in an emotional and intellectual comfort zone distances those nearing Judaism from ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods and cities, Greenwald says. "The Ultra-Orthodox world is very absolute. This is in stark contrast to the postmodern world, which is full of questions and relativity. For Baalei Teshuvah who were used to this, and were accustomed to a great emotional and intellectual freedom, it's challenging to fit into the classic ultra-Orthodox framework. How can they send their children to an ultra-Orthodox cheder if they don't agree with various practices of the cheder that, although not halachic, are taken for granted in the ultra-Orthodox public? For them, it's a prison. Many are satisfied with adhering to the Shulchan Aruch, not seeking additions and stringencies.

"We, veteran Baalei Teshuvah, left everything behind and dealt with life's realities in the ultra-Orthodox community. But it was not easy for us either. Sometimes, these were deep mental changes. For instance, as a parent of children in a cheder, I felt I didn't know whether the compliment the teacher gave my child was sincere or not. Baalei Teshuvah are used to very open and honest discourse between people. In the ultra-Orthodox community, there are different codes of conduct. It's difficult."

The book 'To Know the Land of Your Way'

The book 'To Know the Land of Your Way'It's commonly said that it's easier for Baalei Teshuvah who move to the periphery.

"This is true at first, but even these communities are changing. A few years ago, we established a unique Baalei Teshuvah community in Haifa. Why is such a community needed in a place like Haifa? Although Haifa has a longstanding, open-minded, established community, as young couples from Jerusalem and Bnei Brak arrive, the community changes. Suddenly, the old Talmud Torah, which accepted everyone, is not good enough, and they open a cheder with typical 'Bnei Brak' rules and codes. This happens in many places. We have a member in the community, a Technion graduate engineer, who almost moved to another peripheral community, which promised to be inclusive and united, with Ashkenazim, Sephardim, Baalei Teshuvah... At the last moment, someone internally explained to him how the community indeed operates, and he backed out. He's a very individualistic person, engaged in Torah study during the day – but in his own way. He wouldn't have integrated into that community."

Isn't it easier to integrate into Sephardi communities?

"It depends. If someone connects to Sephardi roots, it will be easier to fit into a Sephardi ultra-Orthodox community. But today, there are many Sephardi Baalei Teshuvah who are very 'Israeli' and do not identify with the Sephardi character of these communities, although in the way the ultra-Orthodox sector works, they are automatically classified as Sephardi. I once met an Israeli Baal Teshuvah who spent many years in the US, a psychology student, of Sephardi descent. But in what way is he Sephardi, other than his prayer style? He is very distant in nature from Israeli Sephardi culture."

So who are the Baalei Teshuvah coming to these special communities?

"People who want to draw closer to Hashem, but also through emotional and social connections that are very open and inclusive. The ultra-Orthodox community scares them. Today's Baalei Teshuvah are very individualistic and not ready to give up this individuality. They seek an environment that will accept it. It's also important to remember that, unlike the Baalei Teshuvah of the past, today's Baalei Teshuvah know something about ultra-Orthodox Jews and returning to Judaism. And the model they have is not Uri Zohar but Evyatar Banai. Someone who continued his career, who didn't disappear into a yeshiva. And that's the model most of them overwhelmingly want to adopt.

"Alongside this, there are also veteran Baalei Teshuvah, like myself and my family, who after many years in an ultra-Orthodox area find a home in a Baalei Teshuvah community. There is a process called 'repentance on repentance.' It's not that one regrets the return to religion, but regrets unnecessary extremism that led to giving up on things without a valid reason."

How do you sum up your experience in such a community?

"It's a very liberating experience. We didn't know how much until we moved here seven years ago. We didn't have practical issues in the ultra-Orthodox public, the children studied in the most prestigious Yeshiva Talmud Torah in Jerusalem. But here, we don't constantly feel the struggle with the ultra-Orthodox world. We live outside the local ultra-Orthodox community, and as long as it doesn't exert the pressure of absoluteness on you – you can appreciate it more objectively. Perhaps it can be said that many veteran Baalei Teshuvah have returned to choosing and stopped mimicking their neighbors."

Most of these communities are also led by Baalei Teshuvah.

"Correct. Also, outreach organizations and yeshivas for Baalei Teshuvah have included veteran Baalei Teshuvah in their staff in recent years. As Rabbi Brook, head of the "Netivos Olam" Yeshiva, said: 'There's nothing to be done; they understand them better than we do.' With all the goodwill, native ultra-Orthodox individuals are not aware of how deeply ultra-Orthodox education is embedded in their souls. It's very hard for them to enter the mind of a Baal Teshuvah. Just a small example: I, as a 31-year-old Baal Teshuvah, discovered that I hadn't tied my shoes correctly until then because I didn't know the law regarding tying the left shoe first. When an adult discovers they don’t even know how to tie their shoes correctly – that's an experience someone from the outside cannot understand. By the way, as a result, there is much information that ultra-Orthodox individuals take for granted and don't even consider teaching to Baalei Teshuvah.

"Baalei Teshuvah can also guide Baalei Teshuvah on topics where religious material is lacking, creating that material. One Baal Teshuvah wants to know the Torah's view on painting, the other on theater. You don't find this in common books, and suddenly you need new material. A native ultra-Orthodox doesn't understand conflicts like the issue of Independence Day for a Baal Teshuvah: for thirty years, he celebrated and suddenly it became nothing. In the ultra-Orthodox world, these matters aren't discussed."

The new book Greenwald is working on will address exactly these issues. "I have lots of material from the years when I had a kollel in Jerusalem, from the years here in Haifa and from writings in 'Adraba.' I'm writing about finding each one's 'blessed vessel,' finding their unique path. I'm writing about the mission of Baalei Teshuvah in our generation – their ability to draw others closer to Judaism precisely because they remain in their initial place, maintaining interaction with their previous society. Issues of finding a halachic approach, marriage, education, leisure culture, and Independence Day. Many matters that are important to today's Baalei Teshuvah, who do not intend after two years in teshuvah to move to Bnei Brak but are planning to remain in Tel Aviv, for instance, permanently. More dilemmas and suggestions, and fewer assertions and "Torah from Sinai."

How do you define the path you've traveled from 'To Know the Land of Your Way' to your current approach?

"I was forced to reach a change of perspective. By nature, I highly seek ideals, but today I realize how complex everything is and led by Hashem. The challenge for Baalei Teshuvah isn't where 'it's better,' but where 'it's more suitable.' Where they can fulfill their role. Sometimes, you need to recognize that your life until today has prepared you for a specific role, different from the role of a native ultra-Orthodox. And all these things are the result of divine guidance, matching our strengths."

To purchase Yehuda Greenwald's book, "To Know the Land of Your Way".