Faith and Art in Syrian Captivity: The Story of a Yom Kippur War Prisoner

Yossi Tor served at the Hermon outpost during the Yom Kippur War and was captured by the Syrians. The lessons in resilience and survival he learned during those difficult months are applied throughout his life, including in his Judaica creations.

Esther scroll cases with Yossi (Photo: Rafi Kutz)

Esther scroll cases with Yossi (Photo: Rafi Kutz)The Yom Kippur of 1973 is a day many Israelis will never forget. The sirens slicing through the midday air, military jeeps stopping with a chilling screech near synagogues, delivering draft notices to reservists wrapped in tallitot. For Yossi Tor, this Yom Kippur remains unforgettable.

"I served in intelligence and was called up right before Yom Kippur to the Hermon outpost to replace a friend," he recalls. Like all the regular soldiers, the outpost personnel were unaware of the impending attack. There were about seventy soldiers in the post, only 15 of them combat soldiers. This outpost, of high strategic importance with key intelligence and communication installations, was easily overtaken by the Syrians.

Tor, an intelligence operative, watched from his observation point on Yom Kippur morning as Syrians on the other side of the border removed the camouflage nets from their tanks and began moving towards the border. He reported this to his superiors, but received a calming response: everything is fine, no cause for concern.

However, there was reason for worry. At noon, the Syrians began bombarding the Hermon outpost vigorously. Two hours after the shelling began, helicopters carrying Syrian commando soldiers landed near the outpost. The commandos quickly overpowered the outpost and its personnel. What the Syrians did not know was that four Israeli soldiers were hiding from them inside the outpost. Surin Kovliu was in an underground maintenance room, while Yossi Tor and two other soldiers, Moussa Menachem and Daw Vakanin, hid together from the enemy soldiers.

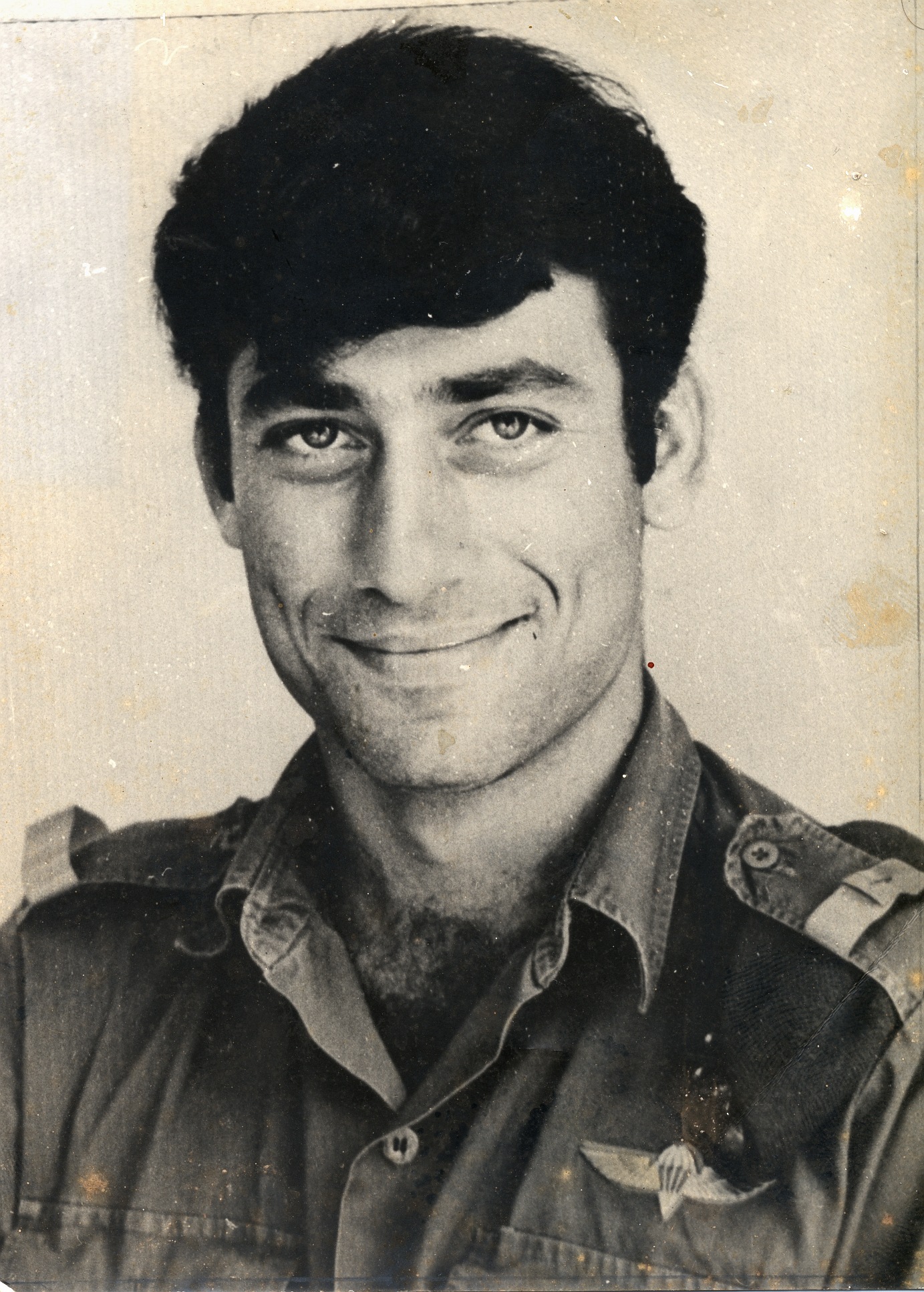

Me as a regular soldier - a photo published when I was 'missing' in the press

Me as a regular soldier - a photo published when I was 'missing' in the pressFor seven days, Tor and his friends managed to keep their existence a secret. "It was like a five-story building, with only one floor above ground, and inside it was a spiral structure. The electricity and communication systems had collapsed, and we hid from the Syrians for a long time. We survived there for eight days with almost no food. Many times, the commando soldiers passed right by us while we lay on the ground, just moments after turning off our flashlight. Each time we said 'Shema Yisrael' and continued to live."

Tor, a religious man, devoted himself to instilling faith and optimism in his comrades. "Two friends had a tough conversation with me, saying they wanted to commit suicide, didn't want to be captured. I tried again and again to explain that it wasn't up to them to decide life or death. Forty years later, when the film 'Seven Days in Darkness' was made about the Hermon outpost during the war, one of those soldiers revealed that his unprimed Uzi was aimed at his head while talking to me, and only because of my words, he put it down."

What gave Tor the strength to survive those terrifying days, among enemy soldiers, without food, constantly in danger of death? "My parents were Holocaust survivors and people of great faith," he says. "But I remember from Yom Kippur, when the chazan chanted the sad words of 'Unetaneh Tokef', 'who shall live and who shall die', I would skip that page. I thought it wasn't relevant. What did we know of death by stoning, for example? But then, when we were in the outpost and the Israeli Air Force was bombing non-stop, the ceiling could have collapsed on us and killed us by stoning – I suddenly understood how relevant the prayers of the High Holy Days were."

After the hiding days inside the captured outpost, Tor and his friends decided to try crawling outside under the cover of darkness. They managed to escape the outpost safely – but fell into Syrian captivity. They were taken to the infamous interrogation facility in Damascus, where they spent four months in isolation, and an additional five months together with the other prisoners. "During the frequent interrogations and torture, I would pray like Hannah 'only her lips moved, but her voice was not heard'. You feel you've reached the end, there's no point in living, but somehow after such a prayer, I would feel my inner strength return."

When he was moved to a cell with the other Israeli prisoners (a total of fifty-three Israeli soldiers were captured by the Syrians), Tor yearned to pray the Amidah properly. "All parts of my body were bruised from torture, but the moment I could stand a little, I would face east and pray. Day after day. Slowly, other prisoners gathered around me, also wanting to pray to sustain life and hope. They asked me to pray aloud, but that was dangerous. One day a miracle happened: when I bent down in the bathroom, charcoal stuck to my fingertips. I mixed the charcoal with the wounded soldiers' cotton padding and created a kind of ink. We received a box with thin wooden strips that I turned into a scribe's quill. On the odor-absorbing cardboard from the box we received, I wrote the entire Shema and Amidah from memory. To write each letter, you had to dip the 'pen' I created in the charcoal. The written prayers were passed among the fellow prisoners so they too could pray."

The prisoners tried every way to keep themselves occupied to maintain high morale, and Tor discovered within himself an extraordinary talent for improvisation. "We received a round box of triangular cheeses, so from the base and lid, I created cards until we had a complete deck. I drew with charcoal a sunset with sailboats drifting in the wind and wrote 'freedom, when will I see it again'. I wrote diaries. I also worked on a plan to smuggle my diaries and drawings from captivity back to Israel." To achieve this, Tor used a chicken bone the prisoners received on the rare occasions before a Red Cross visit. "I dried the bone and sharpened it on the wall until it had a point – and now I had a needle. I unraveled parts of my clothing – the collar, the belt, and more – and hid the things I wrote and created in them, sewing them back with threads unraveled from the clothes."

Bone needle – reconstruction of the needle from a bone, which I used to hide the documents in my clothes

Bone needle – reconstruction of the needle from a bone, which I used to hide the documents in my clothesYossi Tor carried the lessons from captivity with him into his subsequent life. "I give lectures in Israel and around the world, sharing the toolbox for coping that I developed in captivity," he says. "I learned that even if a sharp sword rests on your neck, you must not despair, whether your crisis is health-related, financial, or marital. I learned resilience and try to pass it on."

Fifteen years after returning from captivity, Yossi Tor returned to the field of art and creation. "As it was decreed that the more they were oppressed, the more they multiplied and spread. The Syrians beat me terribly in the hands, and I could have become disabled – and here I am, creating with both hands." Today, he specializes in creating sacred objects from wood: "The trees I work with, like olive, carob, and oak, grow for thousands of years in the Land of Israel and are mentioned in the Bible." Among the products he specializes in are Esther scroll cases, which he sees as a special mission in their creation. "For me, it’s about restoring the crown to its former glory. In recent decades, most Esther scroll cases have been made by Arabs from wood coming from Jordan. I wanted to be a Jew who creates scroll cases from wood grown in the Land of Israel."

As in everything, Tor sees an essential life lesson in his wooden creations. "When I finish creating a vessel, the silent, inanimate wood transforms into a living, breathing product that gladdens hearts."