Personal Stories

Rehabilitation Behind Bars: The Unique Prison Program Reviving Lives at Hermon Prison

The rehabilitative model, spiritual growth, and the power of giving inside one of Israel’s most transformative prisons

- Shira Dabush (Cohen)

- |Updated

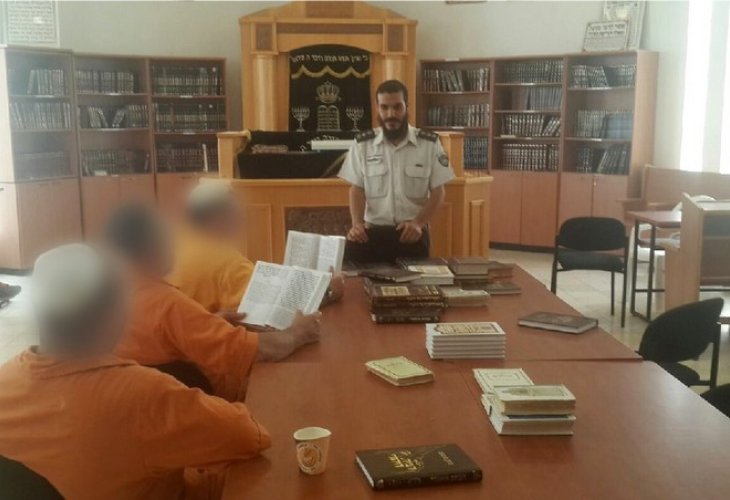

Rabbi Ohonona in the study hall at the prison

Rabbi Ohonona in the study hall at the prisonAs the rabbi of the women’s religious program at Hermon Prison in northern Israel, Prison Officer and Rabbi David Ochanuna is part of a unique and extraordinary mission. This is not “just another” correctional facility with standard programming. Hermon Prison is built on a rehabilitative, therapeutic model. Inmates who arrive here know that with continuous, honest personal work and full cooperation with the therapeutic staff, they have a real chance to leave prison with a completely different life than the one they had when they entered.

Although the inmates here serve relatively “short” sentences of up to five years, Rabbi Ochanuna says that working with them is no less challenging than working with prisoners incarcerated for serious, long-term crimes.

“We treat inmates dealing with many variations and levels of addiction — drug addiction, alcohol addiction, and various forms of violence,” he explains.

What Makes Hermon Prison Different?

An inmate who arrives at Hermon enters a complete process of re-socialization — essentially, a structured re-education. “A full team of psychologists and professionals builds a complete treatment plan for each inmate, from A to Z,” says Rabbi Ochanuna. “The goal is singular: to help them rehabilitate fully and become capable of functioning as regular members of society once they’re released.”

One surprising detail is that out of the 600 inmates in the facility, only about 60 belong to the Torah wing. Why so few? Because joining this wing requires passing a special acceptance committee, which includes a personal interview with the rabbi and careful assessment of the inmate’s seriousness and genuine dedication to change.

“In the Torah wing, we have expectations that don’t exist elsewhere,” he explains. “An inmate who wants to join it can’t just declare he intends to keep commandments — he must actually observe them consistently for a period of time.”

Daily Life in the Torah Wing

The inmates’ routine is structured yet varied. “On the one hand,” Rabbi Ochanuna says, “they have their own community life, freedom, and personal space. On the other hand, they must attend fixed times for prayer and study in the Beit Midrash. In addition, they participate in therapeutic groups where they learn tools for life — and this is where the religious aspect comes in: helping the inmate identify his character traits, correct them, and overcome emotional struggles tied to his addiction.”

“There Are No Bad People — Only Bad Actions”

“In my position — and in the role of the entire guidance staff, there is no place for judgment,” Rabbi Ochanuna says firmly. “We must separate the action from the person. That is our guiding principle. We are here to accept everyone, love everyone, and help everyone — whether their offense was small or large. My job is to instill values that no one ever taught them, which is exactly why they ended up where they did. Every person deserves a second chance, and God is compassionate to all His children, no matter how far they’ve fallen.”

Still, he makes it clear that the work is anything but easy. “It is incredibly difficult and complex to engage daily with people society has rejected. If I don’t believe that each inmate can rise, change, and build a better life — then I have no place here. Truly. And if that day ever comes, that will be the end of my career, because my entire sense of purpose comes from helping these people — from listening to them, smiling at them, and knowing that after one conversation with me, a person decides not to end his life. Do you understand what kind of fulfillment that is? It’s indescribable.”

Encouraging Inmates to Give Back: The “Contribution” Project

Beyond regular programming, there are special initiatives. “One of them,” Rabbi Ochanuna explains, “is a very meaningful project called ‘Contribution’, established by my predecessor. It encourages inmates to submit proposals for programs whose primary goal is giving and helping others. It can be anything such as organizing a group to recite Kaddish at memorials, volunteering efforts for the community, and so on.”

Only inmates with a positive disciplinary record may submit proposals. Participation carries tremendous weight for the inmates and benefits them in extraordinary ways.

Learning to Give: A Foundation for Real Change

“You have to remember,” Rabbi Ochanuna says, “that these are people who not only never learned what real giving is — they rarely helped anyone. They were always on the receiving end. People who don’t know how to give must learn the basics: what giving is, why it matters, and what someone who gives sincerely gains from it. Anyone who gives becomes more refined, less coarse in character — and when they do the work honestly, the behavioral change is immediate.”

Do the inmates choose their own volunteer path?

“There is freedom of choice, absolutely,” he explains, “but we also help direct each inmate toward giving in the area he's naturally good at. This makes the giving more internal, more meaningful. For example, a former driving instructor will teach a class about road safety, including the Jewish principle of ‘and you shall guard your lives.’ A cook will volunteer to prepare meals for everyone and teach a halachic point related to food. The key is that the experience should be positive and meaningful — not forced.”

Special Atmosphere Before the Holidays

Before Jewish holidays, the prison takes on a visibly different atmosphere. The facility fills with a sense of holiness, and the highlight is hosting visiting rabbis who share their personal stories, offer inspiration, and lift the inmates’ morale.

“Today,” he recalls, “a rabbi visited us together with a terminally ill patient who told his story. The inmates were deeply moved — some cried, others were inspired by how he found good even in his suffering. Throughout the year, the Beit Midrash operates from 8 a.m. to noon, which means my time for personal conversations with inmates is limited. But during the holidays, I increase my availability as much as possible for listening to their requests, addressing issues quickly, and bringing external speakers and singers. Personal stories, Torah talks, or artistic programs strengthen the inmates tremendously.”

How Does Rosh Hashanah Look Inside Hermon Prison?

“During the holidays,” Rabbi Ochanuna explains, “there is a higher level of participation in prayers and rituals. We must accommodate more than 150 inmates — not only those in the Torah wing. In every unit there will be someone leading the holiday service, reciting all the blessings.”

Preparations include:

Prayer books for everyone

Volunteer cantors

Organized prayer schedules

Holiday seder plates with symbolic foods

Festive decorations in the dining hall

They also prepare for individual shofar blowings in the isolation wing, for inmates who cannot leave their cells.

“We are aware,” he says softly, “that a person inside a ‘cage’ will not easily feel spiritual elevation or joy during the holiday — no matter how much gold you coat the cage with. Still, we hope and pray that we can ease, even slightly, the pain of being far from family and normal social life. And we hope to bring them as much joy as possible — at least during this sacred and uplifting time.”