Beginners Guide

What Does It Mean to Pray With Intention?

Must we focus on the meaning of each and every word for our prayer to be considered intentional?

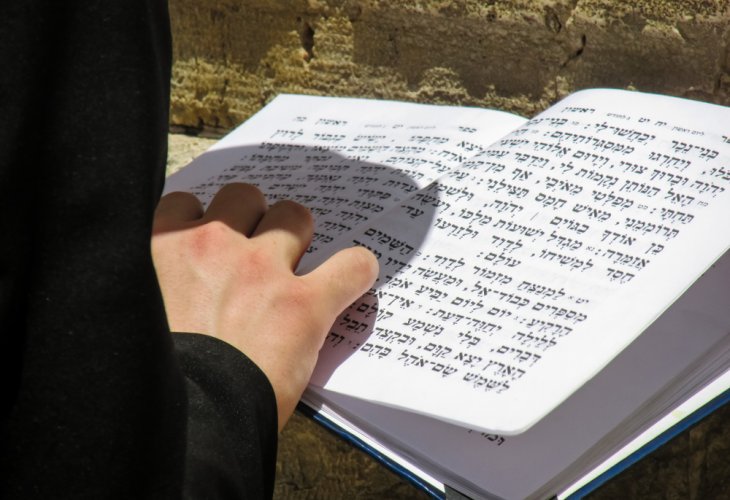

(Photo: Shutterstock)

(Photo: Shutterstock)The issue of intention in mitzvot has been extensively discussed in Jewish law. The Shulchan Aruch states that "mitzvot require intention" (O.C. 60), meaning that when performing a mitzvah, one must intend the action to be performed for the sake of the mitzvah. Consider the mitzvah of the Four Species. Imagine someone walking down the street who sees a case containing the Four Species, which has fallen from someone's hands. He picks up the case and even waves it in the four directions to find its owner, but did he fulfill the mitzvah? Clearly not. The Shulchan Aruch clarifies that only if he truly intended his actions as a mitzvah does it hold halachic significance. Another example is a child practicing for his Bar Mitzvah by reading from the Torah portion V'etchanan, which includes the verses of the Shema. The child reads them beautifully morning and evening, but even then, it cannot be said he fulfilled the mitzvah of reciting the Shema, even though he read every verse with care. This is because he did not intend to fulfill the mitzvah. The basic intention in a mitzvah is thus the very desire to fulfill a mitzvah. Opposite to this is a state of "absent-mindedness," where one acts unwittingly or without prior intention.

Upon the basic intention, further intentions of the mitzvah's content can be added – whether simple intentions or those according to the mystical teachings, etc. For example, Rabbi Saadia Gaon lists ten reasons for blowing the shofar, including remembering the sound at Mount Sinai, recalling the Day of Judgment, and longing for the gathering of the exiles of Israel. However, even if at the time of the shofar blowing, one does not have these intentions in mind, but merely intends to fulfill the mitzvah as commanded by Hashem in the Torah, there is no flaw in the essence of the mitzvah performance.

This is true in matters of prayer as well. The basic intention in the mitzvah of prayer is the very desire to stand before Hashem. Therefore, anyone holding a prayer book and standing to pray is indeed fulfilling the mitzvah of prayer with intention. If asked, why are you holding the prayer book, the answer would be: because there is a mitzvah to pray, and I wish to stand before Hashem.

And yet, this intention is not the highest; the Chazon Ish described it as a "dull" intention (compared to a clear and pure intention): "Anyone standing to pray is not considered absent-minded, as there is always a faint awareness that it is a prayer before the Blessed One. But the mind is not fully alert, and a faint awareness suffices post-factum, but it is not so desirable and acceptable." Yet, this is still prayer with intention. Even one who prayed to stand before Hashem, if intrusive thoughts overwhelmed him during the prayer, or if he was not focused on some parts, it is still considered that he prayed with intention. Only if his mind was so distracted that he was not aware he was standing before Hashem, may it be possible that he did not fulfill the mitzvah at all.

Rabbi Chaim of Brisk similarly explained that there are two intentions in prayer: the first is the feeling of standing before Hashem, as in "I have set Hashem always before me," which is the more basic intention we have seen. The second, which requires greater effort, is that of understanding the words, and here one should indeed strive, as we shall see later.

The Chazon Ish's explanation can reassure many who feel that they never concentrate during prayer- because anyone who intends to pray fulfills the obligation of prayer, even if not in an exquisite manner. We are fortunate to stand before Hashem and address Him as a child speaks to their parent.