Personal Stories

From Ponytail to Prayer: An Artist’s Return to Faith

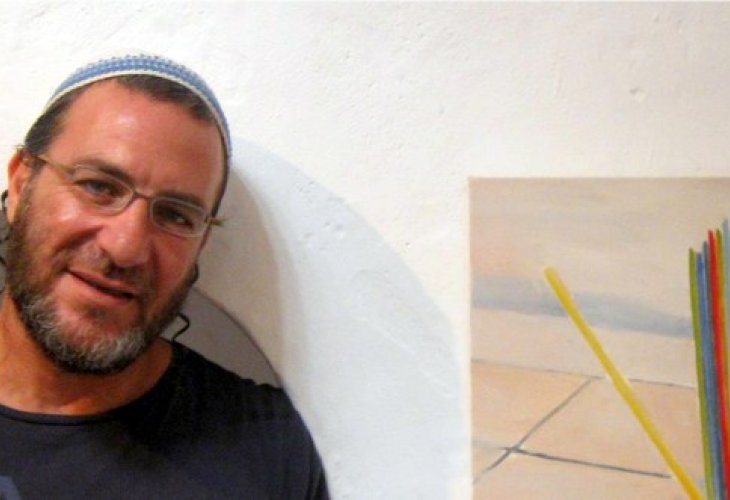

Painter Shimon Pinto reveals how art, longing, and inner truth guided his spiritual return and gave new meaning to his work and life.

When Shimon Pinto was only eight years old, he came back from summer vacation and handed in his sketchbook to his art teacher. Inside were drawings inspired by Renaissance masters. But what surprised the teacher even more than the talent was the depth behind the drawings. “I remember sitting for hours at my desk, going over the notebook again and again,” Pinto recalls. “My mother begged me to go outside and play with the other kids, but I couldn’t tear myself away. I just kept researching and drawing.”

Looking back now, Pinto says that this notebook opened a doorway to a kind of wisdom he could never have grasped alone, a wisdom he now understands as a gift from Hashem. “Even as a child, I sensed that all these great artists were trying to hide the existence of a higher power. But no matter how they tried, it came through anyway.” When his teacher asked how he liked the project, young Shimon replied, “At first it was fun. But then it became sad.” The teacher, surprised, asked him to explain.

“I said, ‘Here you see a thick line, and that means something. Over there a thin line and sadness. Why didn’t they just write how they felt? Why did they hide it in strokes and smudges?’” The teacher was so moved that he invited Shimon to meet privately and continue sharing his insights.

Years later, Pinto still sees that early experience as a kind of spiritual awakening. “It was probably a one-time flash of clarity, the kind many children have but don’t remember.”

That inner spark stayed with him and would later shape his entire journey. During his studies at Ben-Gurion University’s Faculty of Art, Pinto began to feel something deeper stirring. “Through the lines, shapes, and colors I painted, I began to truly find Hashem. That early illumination returned, and I found myself torn between two worlds, one pulling me back to Jewish tradition and the other holding me in place.”

For years he remained in this tension, unsure how to let go of the secular life he had grown up with. But one day, he made a bold decision. “I had a long ponytail. One day I came home and decided to cut it off. I did a kind of personal chalakah (a traditional first haircut, usually at age three), and from there everything flowed, the kippah, tzitzit, Torah learning. Once I took something on, it stayed.”

His first solo exhibition was held in Jaffa’s historic Turkish Bath in 1996. It was a great success. But when critics asked where he had studied formally, he realized he needed to officially complete a degree in art. “Entering art school felt like a child walking into a candy store. The tools I received were like sweet treats for the soul.”

Even in school, Pinto stood out. “I learned the rules like everyone else, but I always stood on the side, looking for ways to bring my inner world into my work.”

In his painting “Mimouna,” he portrayed a figure seated at a table filled with traditional Moroccan treats like mufleta. He describes it as his way of blending his Eastern roots with Western painting styles. “It’s like Claude Monet’s ‘Haystacks’ only instead of planting wheat, my figure is planting candies.”

In his series on mikvah (the ritual bath), Pinto plays with presence and absence. Inspired in part by David Hockney’s famous pool paintings, Pinto's works have no water at all. Instead, the paintings show hints, a rod, a step, a pair of slippers. “There is more ‘nothing’ than ‘something,’” he explains. “For me, the mikvah represents entrance into purity. These works are my gift to Israeli society, showing that it’s possible to live differently with more simplicity and inwardness.”

A few days before our conversation, Pinto had just returned from his first solo exhibition abroad, in Los Angeles. Until then, he had always told Hashem he wouldn’t leave Israel unless it was truly a mission. “I said two things would have to be true: one, it would happen on its own, without me chasing it, and two, I would feel deep down that it was right.”

And that’s what happened. He flew for the first time in his life, carrying little more than his tefillin and some basic materials. He arrived in a wealthy, materialistic part of L.A., where actors and businessmen earn more in a day than most do in a year. But what he saw there surprised him. “I saw people truly moved by the colors, the brushwork, the energy of the figures. There was such a thirst in the air for meaning, for authenticity, for something real. That reminded me how grateful I am for the path I chose.”

What does painting mean to him now, as a baal teshuvah (someone who has returned to Jewish observance)? “Painting for me is like a gem of Torah. Just like I daven (pray) every day, I also paint every day. Not for results, but because it expresses my soul. Painting is a practice of longing, you reach toward it but never quite catch it. The artist is always just outside the work.”

And like the process of teshuvah, painting holds endless interpretations. “Each person brings their own past and beliefs into it. Sometimes that causes tension. But the key is to remember where you came from. In both life and art, people try to assert their own version of truth. That’s where conflicts begin.”

Pinto, who calls himself “a hybrid person, religious, Moroccan, a kind of Sufi philosopher living in a secular world,” says that today he feels no contradiction. “I contain all of it and live in peace. Real teshuvah is seeing the other person in front of you through the other that lives within you. To realize that the other is already a part of you.”

And how do you get to that place?

“Through complete honesty with yourself and a lot of prayer,” he says. “There’s no other way.”