Personal Stories

A Shabbat Story: The Shabbat Chicken That Taught a Lesson in Humility and Wisdom

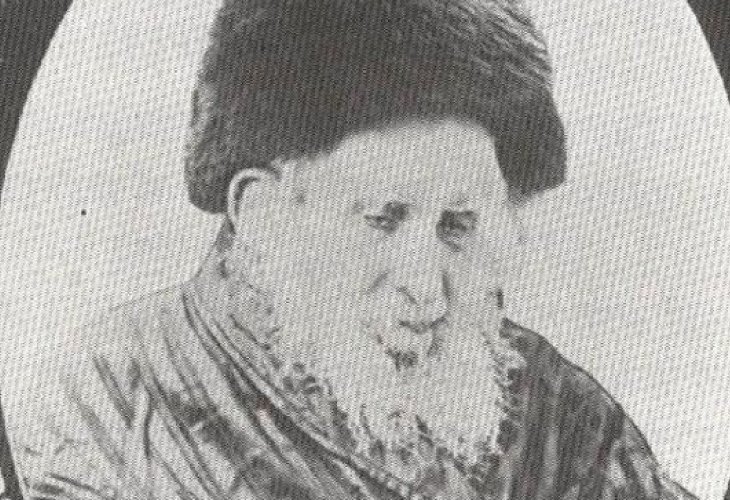

Two stories of halachic insight and heartwarming humility from the life of Jerusalem’s Rabbi Shmuel Salant.

The lesson was in full swing when a small girl appeared at the doorway, holding a slaughtered chicken in her hands. Her mother had sent her to Rabbi Shmuel Salant, the elderly and respected rabbi of Jerusalem, to ask whether the chicken was kosher.

Even though he was in the middle of teaching, Rabbi Shmuel whose gentle nature matched his great wisdom stopped speaking and turned toward the girl with kindness.

“What can I help you with, my daughter?” he asked warmly.

Shyly, the girl explained that her mother had sent her to ask if the chicken was kosher. Rabbi Shmuel invited her closer. He examined the chicken carefully, turning it over and looking it over from all sides. After a few moments, he handed it back to her and said gently, “Go tell your mother she made a mistake and sent the wrong chicken. Ask her to send the other chicken she slaughtered today.”

About thirty minutes later, the girl returned with a second chicken. Rabbi Shmuel checked this one as well and gave her his ruling.

Once she left, the students around him looked at each other in amazement.

“How did our teacher know that two chickens had been slaughtered today?” one asked. “Was this divine inspiration?”

Rabbi Shmuel smiled humbly.

“There was no divine inspiration here,” he said. “No prophecy either. With the first chicken, there wasn’t any halachic question at all. I figured the mother probably slaughtered two chickens, and in her rush or confusion, she sent the wrong one. So I asked for the second. That’s all.”

And while we’re on the subject of chickens and Shabbat…

In the courtyard of a dear Jerusalemite named Rabbi Yehoshua Vilner, many chickens were raised. It was part of the family’s livelihood. But Rabbi Yehoshua, in quiet acts of kindness, would often give eggs and sometimes even full chickens secretly and for free to Torah scholars in the city who were struggling financially.

One Friday afternoon, just before Kabbalat Shabbat, Rabbi Yehoshua stood outside Rabbi Shmuel Salant’s synagogue, chatting with a few friends. He told them about a particular chicken in his yard that was filthy with dust and lice. It looked neglected, and he began to wonder whether something might be wrong with it maybe it wasn’t kosher.

Wanting to be sure, he approached one of the great Torah scholars in Jerusalem and asked for a halachic ruling. The scholar studied the relevant sources and confidently ruled: the chicken is kosher.

As Rabbi Yehoshua was sharing this conversation with his friends, Rabbi Shmuel Salant happened to walk by. Upon hearing the situation, he paused and remarked thoughtfully, “If you’re asking my opinion, the chicken isn’t kosher.”

Everyone was surprised. It was well known that Rabbi Shmuel was usually inclined to be lenient, not strict. And this time, the question had already been answered by another great scholar, who had ruled it permissible. Why would Rabbi Shmuel go against that and declare it forbidden?

Rabbi Shmuel saw their puzzled faces and explained.

“You’re right there’s nothing written in the halachic texts that would automatically forbid this chicken. But think about it. A healthy chicken is able to turn its head and clean itself. If this one is so dirty, it likely means its neck vertebra is broken. And a chicken with a broken vertebra is treif, not kosher.”

His words made an impression. After Shabbat, some of the men hurried to Rabbi Yehoshua’s house to check. And sure enough, they found that the chicken’s vertebra was broken, making it unfit to eat according to Jewish law.

When the original scholar who had permitted the chicken heard how Rabbi Shmuel had reached his conclusion through logical observation alone, he was full of admiration.

“Indeed,” he said, “Rabbi Shmuel Salant is chad b’dara, one of a kind in his generation.”