Personal Stories

From Prison Cells to Torah Study: A Story of Hope

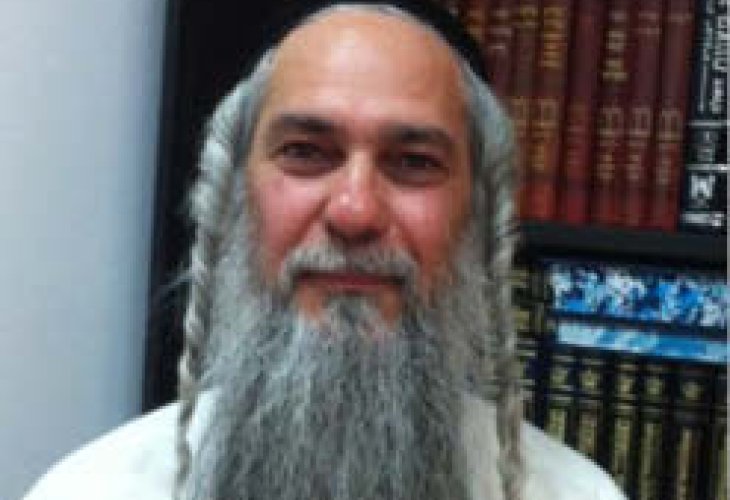

How Avinoam Cohen, once secular, now leads inmates from crime to character rebuilding through Torah, boundaries, and faith in Hashem’s redemption

- Eti Dor-Nahum

- |Updated

When Avinoam Cohen sees a former prisoner become religious, build a family, and study in a Jerusalem kollel (a full-time Torah learning community), his heart fills with hope. For more than ten years, as the director of Torah rehabilitation at the Prisoner Rehabilitation Authority, Cohen (51), a ba’al teshuvah himself (someone who returns to Judaism), has helped transform lives. Last year alone, 133 inmates chose to reconnect through Torah and were accepted into his program.

One of the most touching stories he shares is of Yaniv Eliasaf, a Palestinian who converted to Judaism. Behind bars, Yaniv began observing Shabbat and tfilin, and washed the synagogue. Today he’s a practicing Jew who even cleans the shul he prays in. As Cohen explains, “Torah is a healing tool. It gives structure and true freedom.”

Born in secular Tel Aviv, Cohen grew up in a home that wasn’t religious, though his grandmother covered her head and Shabbat was felt at his grandparents’ house. As a teen, he balanced evening studies with working days following his father’s example of hard work and responsibility.

He enlisted in the army, studied, and worked two jobs. But he still sensed something deeper was missing. At 28, a Shabbat meal at his sister’s home opened his eyes: the peace, the challah, the sacred time. Soon he began wearing tfilin (phylacteries), tzitzit (fringes), and a tallit katan (small prayer shawl), until months later he even wore a kippah.

His family and friends were surprised, asking if someone had died. Cohen joked, “Yes I’m mourning my evil inclination.” He kept his same job and studied Torah after work alongside his boss.

He married and later dove into Kabbalah and character growth. After 20 years at the post office, he joined the Prisoner Rehabilitation Authority, dedicating his life to uplifting others. His days begin at 1 AM with hitbodedut (personal prayer), mikveh (ritual immersion), and Torah study before preparing his family and heading to work.

In his role, Cohen personally assesses inmates, develops tailored rehabilitation plans mixing therapy and Torah, and supports their spiritual growth. He explains that committing to mitzvot (commandments) and Shabbat offers both structure and deep joy. Parole boards favor such programs because they work.

One inspiring case involves a crime syndicate member who entered prison for manslaughter. He later dedicated his life to studying Torah, built a family, and joined a kollel, seeing his study and community as spiritual tikkun (repair) for his past. “He pushes others into kollel,” Cohen says. “For me, seeing him with a stroller gives me the strength to continue.”

Through these stories from ex-criminals to prisoners to a Palestinian convert, Cohen finds purpose. “Our work is like Sisyphus,” he reflects, “endless. But Torah gives us power and faith to go on.”