Why Do We Get Goosebumps? The Hidden Science Behind Human Hair and Ears

Discover the unseen design within the tiniest body muscles.

- דניאל בלס

- פורסם כ"ה תשרי התשע"ט

(Photo: shutterstock)

(Photo: shutterstock) #VALUE!

In this latest article of our series, we’ll explore two more examples often mistaken as "vestigial organs" due to a misunderstanding of their function in the human body, answering the following questions:

A. Why do hairs stand on end, creating "goosebumps"?

B. Why do we have small muscles that enable us to move our ears?

* * *

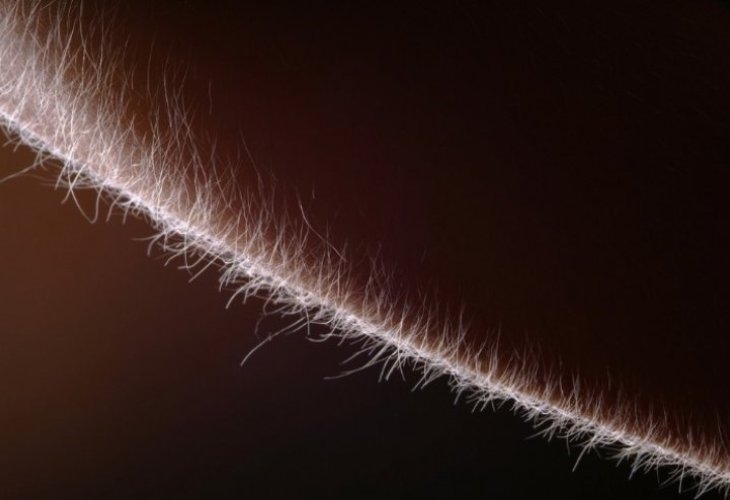

The Magic of Hair Muscles

Hair follicles contain tiny muscles (Erector pili muscles), which cause hairs to stand up when we’re scared or cold. In furry or feathered animals, this helps deter predators by making them look larger and more imposing, while also trapping warm air to maintain body heat.

These small muscles also exist in human hair follicles, causing "goosebumps"—tiny bumps on the skin when we're cold or excited. Researchers even use this mechanism to gauge positive emotions in people.

These muscles benefit humans in several ways: they help squeeze oil from sebaceous glands connected to the hair follicles, lubricating the skin (according to Wikipedia: "A sebaceous gland is a small gland in the skin that opens into a hair follicle").

Additionally, the process assists in body warming: contraction of the hair muscles generates slight heat. When that isn’t enough, the body triggers shivering, contracting muscles rapidly to generate warmth. Thus, hair muscles are a precursor to shivering.

Another remarkable role of hair follicles is in repairing the outer skin layer (epidermis) after scratches or injury, providing an important source of epidermal cells for skin restoration (reepithelialization). It’s incredible to think that without hair follicles and sweat ducts, even minor injuries might require skin grafts!

[Source: ?Dr. David Menton, Vestigial Organs - Evidence for Evolution]

Follicles also enhance our sense of touch. Biologist Dr. David Menton explains:

Most human hairs aren’t visible, yet they cover the entire body, even on very young children. The primary function of hair is sensory. Each hair follicle, despite its size, is equipped with nerve receptors. Our hairs act like tiny levers that, upon any physical sensation such as a breeze, send signals to the brain."

This capability gives us a heightened sensory experience of the world around us, allowing us to feel the smallest particles on our skin, the moisture, sand, and even a gentle breeze, with precise and detailed awareness—all thanks to the hair follicles on the body, even when the hairs remain unseen.

Beyond these important functions that demonstrate intricate design, there's also the very human experience of "goosebumps." It seems that Hashem intended for us to amplify our emotional experiences through another physical expression. Who hasn't said, "What I saw/heard gave me goosebumps all over! Look at my skin!"—a phrase that signifies intense excitement, sometimes described as a jolt of electricity through the body. Who would want to miss out on such a powerful life experience?

Without hair muscles, we wouldn’t get "goosebumps," and our experience of excitement would be diminished. We must thank Hashem for giving us the ability to feel our emotions across all the skin that covers our bodies, in addition to the potential functions mentioned.

* * *

The Subtle Role of Ear Muscles

While large muscles have obvious mechanical roles, smaller muscles can be hard to comprehend. For example, two tiny muscles within the ear (Stapedius muscle, Tensor tympani muscle), among the smallest in the body, help reduce excessive vibrations that might damage the middle ear's mechanism. Small muscles often adjust and aid larger ones, although their role isn’t always obvious due to their subtlety within a much larger system.

We have several ear muscles allowing some people to move their ears. Their purpose isn’t initially obvious. In animals, their function is clear: ear muscles direct the ear towards sound sources for better hearing without head movement. Why do humans have ear muscles?

Their function might not differ entirely from that in animals. When a person hears a sudden noise, ear muscles tend to contract, alerting the individual and enhancing the body's readiness during danger. When startled, the senses sharpen, and it appears ear muscles contribute to this heightened focus on the sound's source, enhancing hearing acuity. Have you ever heard a surprising sound and felt as though your ears tingled, sharpening your perception of it?

However, the role of these muscles in humans is still being investigated. Biologist Dr. Jeremy Bergman, in his book "Vestigial Organs" (Jerry Bergman, Vestigial Organs, 1990), proposed that ear muscles provide nutrientes and blood to the ear:

"The misconception is that the muscles were only meant for ear movement, like in dogs. They are more than just attaching organs—they serve as a glycogen (energy) reserve, crucial for metabolism. Without their structure, the nourishment of the external ear would be severely compromised. They also enhance blood supply to the organ, reducing the risk of frostbite in extreme cold. If you've ever felt cold ears while skiing in the snow, thank the ear muscles for providing warmth!"

Another potential use might be in earwax removal. It's known that chewing, smiling, etc., make ear muscles move, which might gradually push wax out, aiding in cleaning the ears. Science could still unveil many uses for these muscles.

For instance, it was discovered that ear muscles are closely tied to feelings of fear and positive emotions, suggesting that without these muscles, human experience would be more limited.

As is well-known, the human face boasts complex muscles enabling the finest expression of emotions. Ear muscles amplify and refine human experience, not only in fear but also when smiling or feeling joyful—studies have shown ear muscles move, spreading positive emotions throughout the head.

Moreover, researchers found that unlike easily faked feelings of joy and sadness conveyed by facial muscles, ear muscle movement is hard to counterfeit. Therefore, studies examining patient emotions often monitor ear muscle movements.

In short, research indicates that these muscles help convey emotions perceptible to the individual, designed to enhance our emotional experiences of laughter and joy.

Additionally, Dr. Bergman noted that one of the biggest fallacies in labeling organs or muscles as useless stems from the known fact that unused body parts quickly atrophy. Astronauts lose muscle mass within months in space due to zero gravity. The body conserves energy by wasting away unused muscles: "use them or lose them."

As such, claiming that humans have useless organs or muscles isn't rational. It's implausible they'd be preserved without use throughout a person’s life, let alone across generations.

Since this topic touches upon evolutionary claims, it’s important to state that organ or muscle atrophy signifies degeneration, not "evolution" (in the sense of development, new creation). It's possible that the auditory system was more developed in the time of the first human, with ear muscles indeed moving the ears toward sound, enhancing auditory sharpness. If any organ has atrophied, it doesn’t suggest a creation of a new biological entity but rather a degeneration from original perfection. Hence, these examples are far from evidence of "human evolution."

Ultimately, as we've seen, these muscles have several plausible roles in humans, so it’s sheer arrogance to label them "useless remnants of the human body."