History and Archaeology

Mordechai and Esther: Archaeological Echoes of the Purim Story

Archaeology and history illuminate the real-world backdrop of the Megillah and the lives of Mordechai and Queen Esther

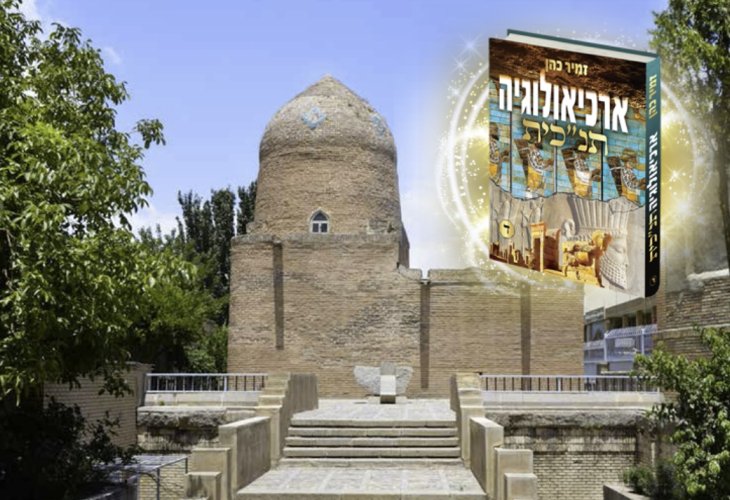

The Tomb of Mordechai and Esther in Hamadan, Iran, today

The Tomb of Mordechai and Esther in Hamadan, Iran, todayAfter the Megillah describes King Achashverosh, his vast empire, the grand feast he held, Queen Vashti’s defiance and downfall, the narrative turns to two new central figures — Mordechai and Esther: “There was a Jewish man in Shushan the capital, and his name was Mordechai… And he raised Hadassah, that is, Esther… When her father and mother died, Mordechai took her as his own daughter. When the king’s decree and law were proclaimed, and many young women were gathered to Shushan the capital… Esther was taken to the king’s palace…” (Esther 2:5–8)

Mordechai in Shushan the Capital

The Megillah emphasizes that Mordechai lived in Shushan the Capital, not merely in the city of Shushan. In the Persian Empire, only officials or people of standing could live in the royal capital itself. This indicates that Mordechai was already a person of rank and respect, even before he rose to prominence as the king’s advisor.

According to the Sages, Mordechai had served as a senior officer in the Persian army, and during wartime another officer, Haman, once asked him for funds to supply his troops — a request Mordechai apparently fulfilled.

Thus, we know several concrete details about Mordechai:

His name, residence, and time period.

His early role as a Persian military officer, and later, his position as a royal official under King Achashverosh

The historian Professor Michael Heltzer, an expert on the history of the ancient Near East, noted a remarkable discovery: “A recently unearthed administrative tablet from the Babylonian city of Sippar mentions a high-ranking official from Shushan named Marduka, who, after retiring from military service, became a royal treasurer during the reign of Achashverosh. His name strongly resembles that of Mordechai the Jew.”

The same name — Marduka, also appears in the Murashu Archive from the city of Nippur, dating to the Persian period. These archives contain many Jewish names written in Aramaic, the language spoken by Jews in Babylonia and Persia at the time.

Some scholars even identify Mordechai’s likeness in a stone relief from the royal treasury at Persepolis, showing a figure standing behind King Achashverosh and his son. Like the king, he holds a lotus flower or goblet, but unlike the others in the carving, his head is uncovered — a detail scholars find intriguing.

Interior of the Tomb of Mordechai and Esther in Hamadan, Iran, today

Interior of the Tomb of Mordechai and Esther in Hamadan, Iran, todayQueen Esther

As mentioned earlier regarding Queen Vashti, Persian kings did not usually record the names of their wives — not surprising, since they often had many. However, historical evidence again comes from Herodotus, who mentions the wife of Xerxes (Achashverosh) by name: Queen Amestris. The initial “M” sound is often dropped in Semitic transliteration, and the final Greek suffix omitted — yielding the familiar name Esther.

“The House of Women”

The Megillah describes how Achashverosh gathered young women from across the empire to the royal compound: “Let all the beautiful young virgins be gathered to Shushan the capital, to the House of Women.” (Esther 2:3)

This House of Women was a large, enclosed section of the royal palace where all the candidates for queenship were housed and prepared. Esther was among them: “And every day Mordechai walked before the courtyard of the House of Women, to know how Esther was and what would be done with her.” (Esther 2:11)

At the ruins of the royal palace in Persepolis, archaeologists have reconstructed, in full scale, the House of Women, based on excavation findings — a physical echo of the world described in the Megillah.