Haman, The Pur, and Historical Insights: Unveiling the Past

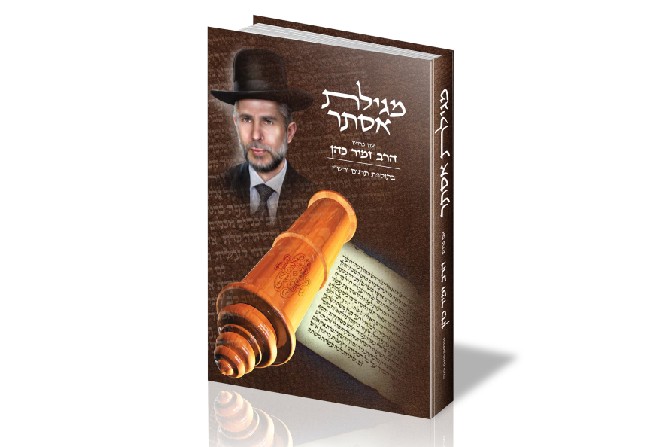

A captivating chapter from Rabbi Zamir Cohen's book on the Book of Esther.

In the beginning of Chapter 3, the Book of Esther describes the meteoric rise of Haman, son of Hammedatha the Agagite, whose prominence is highlighted when King Ahasuerus sets his seat above all the nobles:

After these events, King Ahasuerus promoted Haman, son of Hammedatha the Agagite, elevating him and placing his seat above all the officials with him.[1]

Researchers believe that the name Haman derives from the Persian word hamayun, meaning 'magnificent' or 'great'.[2] Additionally, the name Hammedatha appears on green stone artifacts discovered in the treasure of Persepolis, identified as a significant personality within King Xerxes’ court.[3]

Here is the King's Gate in Persepolis, consisting of two gates with a hall in between. The wall and hall were destroyed in wars.

Here is the King's Gate in Persepolis, consisting of two gates with a hall in between. The wall and hall were destroyed in wars.

After Ahasuerus places Haman's seat above all other nobles, Haman demands the utmost respect befitting his new status. However, Mordecai the Jew refuses to grant him this honor, leading to a pivotal confrontation and Haman’s resulting conclusion:

All the king's courtiers who were at the king's gate would bow and prostrate themselves before Haman, since the king had so commanded. But Mordecai would not bow or prostrate himself. The king's courtiers who were at the king's gate said to Mordecai, "Why do you disobey the king's order?" They spoke to him daily, but he would not listen... because he had told them that he was a Jew. Haman saw that Mordecai did not bow or prostrate himself, and Haman was filled with rage. Disdaining the idea of laying hands on Mordecai alone, Haman sought to destroy all the Jews who were under the rule of Ahasuerus—the people of Mordecai. In the first month, the month of Nisan... he cast the pur—that is, the lot—before Haman...

The verse "Mordecai would not bow or prostrate himself" became one of the most noteworthy phrases in the book, symbolizing unwavering resolve.

The full chapter appears in the Book of Esther with Rabbi Zamir Cohen's commentary.

The full chapter appears in the Book of Esther with Rabbi Zamir Cohen's commentary.In his historical writings, Herodotus[5] describes Persian customs: when two equals meet on the street, they signal their equality by kissing each other. If one's status is lower, they kiss the cheeks; but if much lower, they prostrate themselves before the other.

This mirrors the Book of Esther, where the king elevated Haman to supreme status, commanding everyone, regardless of rank, to bow to him: "All the king's courtiers who were at the king's gate would bow and prostrate themselves before Haman, as the king commanded," but "Mordecai would not bow or prostrate himself." Scholars note: "When asked why, he simply stated he was a Jew. The author didn’t need to elaborate, as it was understood by both the reader and the king’s courtiers that Mordecai, a Jew, could not give divine honor to a human, as his faith forbade it."

However, Midrashic sources explain that an idol hung from Haman's neck.[7] A Jew may bow to a person in respect unless idol worship is involved. Thus, Mordecai's declaration of his Jewish identity clarified his refusal to bow before an idol.

Haman, realizing that Mordecai's defiance was rooted in a shared religious belief among Jews, sought retribution against all Jews. He decided to cast lots, or the pur, in the month of Nisan to determine the most opportune time to carry out his plan. Researchers note that in Persia, as throughout the ancient Near East, the start of Nisan was considered ideal for casting lots, as their deities were believed to decree the fate of the world and mankind for the upcoming year.

Persian Language and Customs in the Book

The Book of Esther peppers throughout terms and names used in ancient Persia, as well as prevalent laws and customs. Researcher Abraham Shalom Yehudah highlighted numerous examples:[9] "Igeret, Achashdarpenim, Achashetran, Botz, Birah, King’s Treasures, Dar, Law, Time, Hor, Karpass, Merchant, Proclamation, Dispatch, Paratim, Officers, Hathach, and more. Names of those at the king’s service, names of the gatekeepers, and of course, Ahasuerus, Esther, and Shushan are Persian names. Standard phrases (technical) used in government offices and documents are also mentioned."

The book also notes ancient Persian customs and laws, such as consulting wise men for times (1:13), seven officials first in the kingdom (1:14), an unchangeable law (1:19), king’s servants (2:2), women’s quarters (2:3), provincial benevolence (2:18), sitting at the king’s gate (2:19), hanging on a tree (2:23), chronicles (same chapter), bowing to the viceroy (3:2), the pur casting (3:7), king’s seal (3:10), commands in every language (3:14), not entering the king’s presence without invitation (4:11), the king's horse significance (6:8), dining sprawled on couches (7:8), and more. Professor Michael L. writes that the author of Esther "demonstrates remarkable familiarity with Persian customs, laws, administrative and social organization of the empire, and the multilingual policy adopted by Persian kings."

* * *

A Jew who believes in Hashem and His Torah does not need confirmation from historical or archaeological records, but for those seeking reinforcement, these insights are invaluable.

For everyone, it is fascinating and enchanting to see these ancient facts and details from the Book of Esther brought to life before our eyes.

[1] Esther 3:1.

[2] Hebrew Encyclopedia, Vol. 14, p. 764, entry Haman.

[3] Yehuda Landy, op. cit., p. 73.

[4] Esther 3:2-7.

[5] Herodotus’ Histories, Book 1, 134-135.

[6] Z. Seidel: Articles in Biblical Research, Israel Bible Society Publications – Book 11, published by the Israel Bible Society via Kiryat Sefer, Jerusalem, 1962, p. 224.

[7] Midrash Rabbah, Esther 6:2.

[8] Encyclopedia of the Biblical World, op. cit., pp. 241-242.

[9] Professor A.S. Yehudah (1877-1951), "Past and Arab: Collected Studies and Articles, Arabic Poetry, Memoirs and Impressions," New York: Agam, 1946, p. 89.

[10] Encyclopedia of the Biblical World, op. cit., p. 215.

Purchase the Book of Esther with Commentary by Rabbi Zamir Cohen